IDFA DocLab is the immersive selection of non-fiction digital and immersive stories that is a part of the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), and they’re having their 19th selection this year. DocLab founder Caspar Sonnen has been doing an amazing job of tracking the frontiers of new forms of digital, interactive, and immersive storytelling since 2007, and he joined me along with his co-curator Nina van Doren to talk about the ten pieces within the DocLab Competition for Immersive Non-Fiction as well as the nine pieces within the DocLab Competition for Digital Storytelling as well as portions of their DocLab Spotlight as well as the DocLab at the Planetarium: Down to Earth program, DocLab Playroom prototype sessions as well as the DocLab R&D Summit.

In trying to describe the types of immersive art and storytelling works that DocLab curates, then they have started to use the term “Perception Art” in order to describe the types of pieces and work that they’re featuring. This year’s theme is “Off the Internet,” which speaks to both the types of works that critique and analyze the impacts of online culture on our lives, but also taking projects that were born on the Internet and giving them an IRL physical installation art context to view them. I’ll be on site seeing the selection of works and also be interviewing various artists who are on the frontiers of experimentation for these new forms of “perception art.”

UPDATE: December 6, 2025. Here’s all of my coverage from IDFA DocLab 2025:

- #1682: Preview of IDFA DocLab’s Selection of “Perception Art” & Immersive Stories

- #1683: “Feedback VR Antifuturist Musical” Wins Immersive Non-Fiction Award at IDFA DocLab 2025

- #1684: Playable Essay “individualism in the dead-internet age” Recaps Enshittification Against Indie Devs

- #1685: Immersive Liner Notes of Hip-Hop Album “AÜTO/MÖTOR” Uses three.js & HTML 1.0 Aesthetics

- #1686: 15 Years of Hand-Written Letters about the Internet in “Life Needs Internet 2010–2025” Installation

- #1687: Text-Based Adventure Theatrical Performance “MILKMAN ZERO: The First Delivery”

- #1688: Hacking Gamer Hardware and Stereotypes in “Gamer Keyboard Wall Piece #2”

- #1689: Making Post-Human Babies in “IVF-X” to Catalyze Philosophical Reflections on Reproduction

- #1690: Asking Philosophical Questions on AI in “The Oracle: Ritual for the Future” with Poetic Immersive Performance

- #1691: A Call for Human Friction Over AI Slop in “Deep Soup” Participatory Film Based on “Designing Friction” Manifesto

- #1692: Playful Remixing of Scanned Animal Body Parts in “We Are Dead Animals”

- #1693: A Survey of the Indie Immersive Dome Community Trends with “The Rift” Directors & 4Pi Productions

- #1694: Reimagining Amsterdam’s Red Light District in “Unimaginable Red” Open World Game

- #1695: “Another Place” Takes a Liminal Architectural Stroll into Memories of Another Time and Place

- #1696: Speculative Architecture Meets the Immersive Dome in Sergey Prokofyev’s “Eternal Habitat”

- #1697: Can Immersive Art Revitalize Civic Engagement? Netherlands CIIIC Funds “Shared Reality” Initiative

- #1698: Immersive Exhibition Lessons Learned from Undershed’s First Year with Amy Rose

- #1699: Announcing “The Institute of Immersive Perservation” with Avinash Changa & His XR Virtual Machine Wizardry

- #1700: Update on Co-Creating XR Distribution Field Initiative & Toolkits from MIT Open DocLab

- #1701: Public Art Installation “Nothing to See Here” Uses Perception Art to Challenge Our Notions of Reality

- #1702: “Coded Black” Creates Experiential Black History by Combining Horror Genres with Open World Exploration

- #1703: “Reality Looks Back” Uses Quantum Possibility Metaphors & Gaussian Splats to Challenge Notions of Reality

- #1704: “Lesbian Simulator” is an Interactive VR Narrative Masterclass Balancing Levity, Pride, & Naming of Homophobic Threats

- #1705: The Art of Designing Emergent Social Dynamics with Ontroerend Goed’s “Handle with Care”

- #1706: Using Immersive Journalism to Document Genocide in Gaza with “Under the Same Sky”

- #1707: War Journalist Turns to Immersive Art to Shatter Our Numbness Through Feeling. “In 36,000 Ways” is a Revelatory Embodied Poem by Karim Ben Khelifa

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Today's episode, I'm going to be talking to the curators of IFA DocLab. IFA is the International Documentary Film Festival of Amsterdam, and they have a DocLab, which is sort of like their immersive and new media section that has been going for 19 years now. They'll be having their 20th anniversary next year, but It's always been a place for experimentation for filmmakers and storytellers and a lot of documentary filmmakers who are able to use all the emerging new media technologies and to start to combine them in new and different ways. It's a very interdisciplinary practice where they're fusing together all these different design disciplines and technology. And sometimes it's not using any technology at all. It's just more immersive theater forms. And so it's really an interdisciplinary fusion of all these different storytelling techniques that are all coming together together. in the context of a documentary festival. Casper Sonnen is the founder of DocLab and I had a chance to talk to Casper and the other main curator of Nina van Doorn to talk about this year's program, but also to reflect upon where they've been at with the DocLab. So this year's theme is off the internet, which is kind of reflecting on all the different ways that we can use immersive technology and experiences to get away from the internet and really be present and embodied, but also just reflecting on the impact of the internet and algorithms on our lives. a lot of different critiques and reflections on these portals of escape that we've been living with for the last 30 to 35 years. So because DocLab is often going out and curating and talking to different immersive creators from all sorts of different backgrounds and disciplines, they often find themselves having to explain how they approach documentary because a lot of people have an idea of what documentary is, but DocLab is really very expansive in the way that it's using emerging technologies to tell stories that are a creative treatment of actuality, a phrase that John Grierson used to describe documentary. But they've been using this term called perception art. So art that is playing with our perceptions, using the full spectrum of our fully embodied experiences to be able to modulate our perceptions and our emotions and our ideas about the nature of reality. So this broader term of perception art is another phrase that they've been using to kind of describe this broader field of immersive storytelling and immersive art. So the festival is coming up next week. I'm going to be there on site seeing all the different work and then talking to as many of the different creators as well. I'll also be covering the R&D Summit last year. I wrote up like a whole 8,000 word report so you can go read that to get all different accounting where they bring together lots of researchers. It's really a gathering of the immersive industry of folks that are in the distribution phase, the people that are there at IFA pitching projects. There's funders that are there. They also have kind of more of an experimental perspective playground that they've started last year where they're inviting creators to show early prototypes to be able to workshop different projects and so there's the digital storytelling competition as well as the immersive non-fiction competition and then the spotlight which is featuring works that are from the broader industry so it's always a really packed week when i go there to IDFA DocLab and I'm looking forward to checking out all the work and then talking to as many of the artists as i can But this conversation should give a really great overview of not only the program, but also some of the deeper reflections of where we're at right now with our relationship to technology and the ways that it's being used to tell stories in new and different ways. So we're covering all that and more on today's episode of the Voices of VR podcast. So this interview with Casper and Nina happened on Monday, November 10th, 2025. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:03:51.414] Nina van Doren: Hi, I'm Nina. I'm a programmer at IDFA DocLog, where I'm part of the team that works on scouting, commissioning, and preparing our annual exhibition of interactive and immersive art, which include also performance, games, and other formats. And I work closely with artists, producers, and with Casper Sonne here to bring these projects to life in a festival setting, basically from early concept to final presentations.

[00:04:17.731] Caspar Sonnen: And I'm Casper. I've had the honor to work with Nina for the last couple of years. And before that, with various other people at IDFA to create the DocLab program, which is the media program of the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam. And it's a program that I started in 2007 when it was initially a small online program that slowly turned into a series of live events, exhibitions featuring interactive documentary art. as we saw over the years with the rise of VR and AI, increasingly other disciplines and other art forms.

[00:04:54.698] Kent Bye: Right. And maybe you could each give a bit more context as to your background and your journey into the space.

[00:05:00.515] Nina van Doren: Yeah, so I came more from a traditional art history background. So mainly studying paintings and sculpture and really trained to analyze form and composition and material and all that. But at the same time, I was really drawn to computers, digital culture and took computer science classes. And so I think where the two sort of intersect, where really the visual arts meet new media or when new media artists start emerging is really what caught my attention most. And also where art history stopped at uni. But it was, yeah, artists like Laurie Anderson, the Belgium Net Art Duo, Jody, Corey Archangel, Olia Lialina, those type of people are really formative. For me, who showed works, technological works that really carry something deeply human and Yeah, often really combining this artistic sensibility with cleverness and humor or using or hacking technologies, exposing often its workings or using it in different ways it was intended for. And besides that, more as a hobby, I love exploring indie games on itch.io, like really browsing through many, many different small experimental projects. That's still really, I feel, say something honest and, you know, all the self-published stuff that's quite raw. I really love that and really directly connects to my love for documentary. Working at IDFA, of course, you know, it's the same sort of impulse, people using media to express themselves. how they experience the world. And lastly, during my studies, I worked for a while as a researcher at Lima, which is Living Media Artists and Archive in Amsterdam, researching early digital works and their preservation, which really told me how fragile and context-dependent these pieces can be. And now at Itva Doglab, shifting more from archiving to programming and from preserving to presentation, I suppose, but also really understanding how one informs the other. And yeah, I guess what keeps me excited is that these forms aren't fixed or a little form of the exhibition. Each year we start planning, not knowing at all what it will look like. And the artists are very much leading what we get to do and get to see. And that makes it feel really exciting. And I think of myself like my role in supporting that process, like helping artists reach audiences and finding effective ways to communicate about new media works and also thinking about how to improve the visibility distribution and sort of long term access. Nice.

[00:07:28.183] Caspar Sonnen: And on my side, I guess I grew up in a household of street theater and visual arts as the background of my parents. So when I went to study as a young boy, I tried to run away from the arts as hard as I could. Ended up still studying general humanities and falling in love with cinema. And having played a lot of video games as a kid on the Commodore Amiga and platforms like that, i also did new media at university in the mid 90s and i think back then i really fell in love with cinema and i really fell out of love with theoretical new media and sort of the huge claims it was making ending up diving further into cinema starting with a group of friends the absalom open air film festival where we brought rare and undistributed films to large outdoor audiences. Started doing interdisciplinary installations at that festival as well, and ended up working at IDFA. And within IDFA, in 2007, as the internet was really becoming mainstream, started to sort of see experimentation on the web as something quite exciting and way more exciting than the theoretical new media stuff about cyberspace that i was trying to learn in the mid 90s and pitched an idea for a program at it and it was gracious enough to say like well write a grant application and run with it and i think back in that day it was really scavenging the internet to find things that would fit something that was non-fiction, that was interactive, that was new media. Stumbling upon the works of people like Jonathan Harris, Vincent Morissette, Aaron Koblen, Kat Cizek, seeing the work that Upian was doing in France. So a lot of stuff in France and Canada at the time. and went with interactive documentary in the early days. And then I think increasingly DocClub has become a program where the art forms and the disciplines that we saw connecting to interactive and digital art became increasingly physical. Through the rise of VR, things became more spatial and physical. Also, the presentation formats became more physical. And I think in recent years, I feel that running away from my parents' visual art and theater background has been a huge failure because I think we've been doing immersive theater and live performance and physical installations more than we've ever done.

[00:10:03.433] Kent Bye: Nice. Well, I always appreciate coming to DocLab because, you know, that John Gerson definition, Casper, that you shared with me back in 2018 of documentary being a creative treatment of actuality. For me, it expanded my idea for what documentary was because there is this split between fiction and nonfiction and reality. You know, on some level, it's all storytelling, but to have something that is a reflection of what's happening in the world right now, I really appreciate what William Uricchio had pointed out, just how much of documentary as a form is at the forefront of all new emerging media, whether it's sound that's independent or color film, just even film in general. So it seems like DocLab is at the frontier of looking at all these new forms of storytelling, but also how people are finding new ways of experiencing stories. And so there's two main sections there at DocLab in terms of the DocLab competition for immersive nonfiction, and then also the DocLab competition for digital storytelling. And there's also a spotlight where you're curating from pieces that have already made their appearance on the festival circuit. And also the dome, I think, is also a format that has overlaps between these other previous sections. But as you start to think around this year's selection, I'd love to hear any high-level themes or ways that you start to make sense of all the different projects that you're showing this year at DocLab 2025.

[00:11:27.042] Caspar Sonnen: Well, the theme this year is off the internet. As you know, the different sections that we have within the festival really serve a purpose for me and Nina when we're curating, when we're looking for work and trying to categorize things. But truth be told, those sections are a guide. There's works that could fit in different categories at the same time, which is a little bit the nature of curating interdisciplinary art. I think the range of works that we tend to show is The key thing that we try to hold on to is, as you said, documentary in its broadest sense. So we're starting to use the term perception art as well a lot. So the program sections are sometimes a bit fluid. The DOM, you mentioned, projects can move between different program sections. And every year, that's why we also have a theme. And that theme is, for us, a little bit a red thread throughout the program. Not every project fits the theme, but the theme kind of is a commentary on what's happening in the immersive world, what's happening in the real world outside of the art world, and what's happening in technology and how people are relating to it. And this year being the 19th edition of DocLab, we're starting to become quite aware that today is a different time than 20 years ago. The way that we relate to technology, the way that we consume and appreciate criticized technology is quite different from 20 years ago. Where 20 years ago, I think the conversation was, what's the relevance of the internet and digital arts and digital technology to our real world? Is it but a distraction or some sort of lofty thing that the kids go to play games on? Whereas I think now we're at a point where increasingly people feel that digital technology and the industry and the people dominating it are having a strong grasp and are influencing the real world maybe in ways that we didn't expect or didn't aspire to 20 years ago. I don't think if you look at your average conversation happening on social media or in regular linear media that you are struck with a huge sense of pride about what interactive technology has brought to the world. If you look at how democracies are being pressurized and affected, I think many of us are starting to become slightly concerned and worried about the grasp that technology is having on the way that we perceive reality and that we process reality and that we yeah even further than that we can see the effects on human behavior there's a lot of isolation anxiety there's a lot of mental health issues there's a lot of criticism increasingly on the way that the internet has become a pervasive part of our everyday experience And I think similarly to other innovations in human history, whether it's fast food and processed food, there's a moment initially where it's all exciting and wondrous. And then after a while, there's a moment where we start to reflect like, hey, are there elements here that might not be so healthy or productive or are we losing certain things? So that's why this year the theme of the Internet is a way to, on the one side, acknowledge that technology is not necessarily all good and all getting us to a point where we want to end up. Even though at the same time, if we see a lot of the works like what DocLab is presenting, these are also works of the internet. These are works that would not have existed without the internet. The artists that we love to showcase are like us, people who embraced the wondrous nature of undefined technologies to see what could be done with it so that sort of conundrum that sort of tension between technology being something we're also starting to become increasingly critical of and at the same time something that we still really are exploring and feel like we haven't achieved its full potential at all is what's bringing us to the theme of the internet this year

[00:15:33.581] Nina van Doren: Yeah, it's a deliberate sort of play on words as well, where the off, you know, especially in spoken, off the internet could mean both, you know, coming from the internet itself, like as talk lab emerges alongside these technologies, but also very much the urge to step off it, or at least off the way it's going. So it's a little bit that protect me from what I want in a way as well. You know, that tension between the desire and self-destruction and freedom and control. We have apps to reduce the use of apps. And yeah, like Casper said, you know, you see many new instances are trying to legislate, at least also in the Netherlands in last year was a first sort of attempt at a major school phone ban. And also recent studies already found like three quarters of the surveyed schools saw a really improved focus so I think yeah we see a lot of people wanting to do less everywhere from the wellness industry to travel brands and resorts you know offering like device-free zones or internet-free cafes so it's It's just things we see emerging while at the same time we're all so addicted and it's all so incredibly convenient. I mean, this interview alone, you know, we're having this online. Our program is very much off the internet, but we also want to very much acknowledge the privilege that's sort of inherent in this. Even being able to step offline, which is definitely not a luxury that just anyone can afford. And there's definitely a sort of correlation also between having already good access and having all those things and then stepping off of it. So we're sort of grappling with all these different things. That's what the theme tries to capture. Yeah.

[00:17:12.984] Kent Bye: Nice. Very cool. Yeah, it feels like we're all wanting to have different levels of digital detox, but I think also the rise of immersive art entertainment where you put your phone away and you're completely immersed into the moment, I think is also a trend that I've been seeing over the years. And I wanted to just unpack a little bit this term of perception art, and hear you elaborate on that a little bit, and then we'll be digging into this year's program. But I wanted to just... take a moment and kind of unpack that a little bit just because, you know, immersive is a term that's been thrown around a lot. Even there's the DocLab competition for immersive nonfiction. And so that it's a part of something you're also embracing. And so just curious to hear any elaboration of this term of perception art and where that came from.

[00:17:59.781] Caspar Sonnen: Yeah, I think perception art is a term that we stumbled upon in conversations this year. Mostly, I think, like the experience of me and Ina, part of our curation is making a selection from works submitted to us by artists that know DocLab really well and that bring us new works and then we're honored to create a space for them. A large part of the program also comes from artists who've never heard of IDFA, who've never heard of DocLab because the interdisciplinary nature of our practice curatorially, meaning that we really actively go out and discover works that we then have to convince that their work makes sense at a documentary festival. Then first of all, they're like, I mean, this is always an interesting conversation because then we encounter the way that people perceive what documentary is. and in many ways people think documentary is educational or it's boring or it's activist or it's telling you what to think or it's left wing or it's whatever and then you get into terms like non-fiction and then it's like yes but isn't documentary constructed itself as well and you're like yes absolutely and yes it is a fictional construct i remember at some point like Herzog famously always said, like, documentary doesn't exist. It's just film. I'll resist the temptation to add a German accent to this, but people can think that a lot of themselves change my Dutch accent into a German accent and you'll get that. And I think even though I agree with Herzog that all film is construct and all art and all media are to a certain extent a fictional construct, there is a difference between a Steven Spielberg film or a documentary film. There is a difference there. And that difference is very much in the perception of the audience. There's a big difference between a mockumentary that is a fictional film, a fictional construct that pretends to be a documentary and a real documentary. The difference is the contract with the audience. And I think what we saw, especially when creating a program, inviting artists, explore different technologies and new technologies that we don't know yet how they work and how they affect us as a viewer or as a creator a lot of the artists that we really love and have been featuring over the years are artists that really specialize in playing with our perception and they don't necessarily fit neatly into a completely fictional work or into a completely documentary traditional documentary work but they are works that acknowledge that they are messing with you as an audience but they're still inviting the audience to bring something of themselves or they are still bringing reality into the work a lot of these artists instead of falling neatly between is it truth or is it fiction is it fact or is it make believe in fantasy they take reality as part of the experience and then try to distort it but doing so facing the audience honestly almost like a magician does like a magician is something else acknowledges gravity and then messes with it i think that's what we see when we look at some of our favorite artists like anagram or what we see what is doing the immersive theater group that we're showing a new work from this year or celine dama who's bringing a new immersive piece to the program all of them are not necessarily doing fiction they're not necessarily doing documentary they're doing something that yeah for us perception art felt like a really good term to describe what those artists are doing look at blur i mean look at craig's piece and i think that was one of the highlights in venice look at a piece like that is that fiction is that reality it's a work that deeply acknowledges that it's a fictional construct and takes you on a ride and as an audience you know exactly that you're being messed with but it's also really real to a certain extent the experience you have is that of going through almost experiencing an amazing magic show I hope this explains, but.

[00:22:10.988] Kent Bye: Yes, yes. And yeah, Nina, I didn't know if you have anything else that you wanted to add.

[00:22:14.891] Nina van Doren: Maybe we can, as also a bridge to talk about the selection, maybe by talking about one of these pieces. And Casper, you mentioned Celine's work. I think it's a great example of that, of like how she plays with perception and how perception art is sort of expressed through this work. It's called Nothing to See Here. And Celine Darman is quite well known also for her virtual reality work. Her earlier work, Opera VR, won a Venice and Merced Grand Prize, I think two years ago. But with this work, she moves from VR to really an interactive installation. It's a kind of modern diorama type of kijkdoos. We have a Dutch word for it, but it's no headset. It's an installation where you invite it to peek into. And then it's very much playing with your sense of certainty, really, of reality. You see yourself standing, and I don't want to spoil too much by talking about it, but it very cleverly uses video and sound to create a sort of double reality. And you're not really sure what's happening anymore. It's a real-time footage with stage, real events. And it's positioned in the The more people sort of walk through the space, the more of these things are being triggered and really mess with your sense of certainty and perception of reality, which is very much also what Celine wants to do, like question yourself on this. Hmm.

[00:23:41.556] Kent Bye: Nice. Yeah. Looking forward to seeing all the different pieces because I think I see DocLab as a really experimental place where a lot of artists and creators are pushing for the frontiers of what you can do with medium. But also, you know, like you said, it's a documentary festival. So it is having some sort of creative treatment of reality. So we're reflecting on a lot of these deeper trends. I could see how coming off the internet and wanting to disconnect, but they're still, you know, in the DocLoud program, it seems like you're still emphasizing ways that people are finding new ways of telling storytelling through different modes of technologies from virtual augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and kind of the fusion of all these different design disciplines. Interdisciplinary is a term that's come up a number of times in this conversation where it's pulling in theatrical elements, cinematic elements, game design elements. architecture, theater, and social dynamics as well, where you're creating unique social experiences with people. So yeah, I don't know where you want to begin with just going through the program. We have both the immersive nonfiction and the digital storytelling, but also at the same time, you said how sometimes some of these pieces can be in multiple categories. So, but Linda, hear us go through the program this year, just to get a little bit of a sneak peek of what folks can expect when they come to DocLab this year.

[00:25:00.689] Caspar Sonnen: Yeah, maybe we can start with one work that I think next to Celine's Nothing to See Here is a really strong illustration of the theme. Another project from the Immersive Nonfiction Competition. It's Handle with Care. I briefly mentioned it already. But I think it's a piece that really, in many ways, symbolizes the types of works that we love to showcase. Handle With Care is a project that we presented the prototype version last year at the festival in our Playroom section, which is a series of events that we use to allow artists to do audience testing, both for real audiences and professional audiences, to test new works or to test a certain technology. And Handle With Care is an immersive theater piece. It's created by Ontroerend Goed, who they tend to describe their work as interactive theater for people who hate interactive theater like themselves. They're also known for making some of the most loved interactive theater pieces in the last 10 or 20 years. They're known more from the Edinburgh Fringe and the immersive theater circuit. But what they do, I think, is incredibly relevant for the world of immersive creation. we've done things with them playing with ai and playing with different technologies but in a way like many theater makers they can show us in the immersive tech world how to do a lot with very little And they're quite a radical group. So they've done big immersive shows, which are hard to set up, which are hard to tour, which are dependent on highly trained actors and technicians. And with Handle With Care, they kind of wanted to do something that could be as lightweight and tourable as they'd ever done. And what it ended up being is basically a cardboard box. with some props, instructions, little things in there. I won't spoil it. But this is a box that a theater can buy. It's shipped to a theater. The box itself has an instruction on top for the reception desk at the theater, where it says, like, well, when the night of the show is, you can sell 40 tickets. And then you have to turn on the house lights, put this box on stage. And the only thing before you leave the room is leave a note on each seat that says the experience will start at the moment that one person opens the box. And that's it. So as an audience, you enter a theatrical space, I mean, a regular theater, expecting to get a show. And you're there with a group of people who have the same expectation, and there's a box on stage. And you're instantly in a social experiment. You're instantly in a moment where it's like, who's going to be the more alpha person who gets on stage and opens that box? And this is where you can see the genius of the interactive creation of Ongelovend Goed. is that this is what the piece is about it's about group dynamics it's about the whole experience is about discovering who we are as a group and messing with us messing with that expectation so how do you create an experience for 40 people where it doesn't become one person leading the rest through. We all know this from an escape room, right? Like there's this one person who's done a lot of escape rooms and he knows how to solve all the puzzles and does it. And then there is a bunch of others. Usually people like me standing in a corner like, yeah, I'm... oh, okay, we do this. Or there's people taking out their phone and asking Chet GPT to solve the puzzles and ruining it for everybody. But it's, this is an experience where all there is is a box with instructions. It's kind of an algorithm for human beings. And yeah, I can't spoil the experience. I haven't done the final version. I've only done the prototype, but I've done that three times and they were radically different experiences. I think two were brilliant. One wasn't that great. And that was when the room was 30 interactive theater students who were all the alpha males. It's a great piece for many reasons. It shows us how we don't need technology to have a great experience, how great it is having to rely on each other, how great it is to not have to put on an itchy, clunky headset, as amazing as that is and as many VR pieces we have in the program this year. It also shows us how great it is to create collective physical experiences and especially to think from day one, how can we tour this? How can we show this and bring the costs down? Because I think as an industry, this is one of our big questions. If we want to get immersive art to the next stage, we do need to acknowledge that at this point, the costs of putting up a lot of immersive experiences are similar to opera. If you look at the cost per user, The costs are steep. This is an example that we can learn from. What will be the VR equivalent of this? It's interesting to think about. In a way, in that sense, this is also a project that goes even further than Ancestors that we premiered last year, Stey Halleman Smart from Orchestra Peace. But that also shows we are yearning for collective physical experiences. And you can see it by the success that Ancestors is having since then. Hmm.

[00:30:32.745] Nina van Doren: Yeah, maybe to tie into this another way that we're trying to bridge that sort of like physicality or to bring digital works into the physical space or play with the off the internet of putting things that are from the internet in a sort of offline setting. The interactive cinema is a new concept that we are trying out this year in which we present different type of interactive documentaries. So these are web-based or games, those type of works that we often also present in like full-blown installations where like one person goes in and there's a whole set design and And this year, we really wanted to focus more on really the collectivity of playing together, the joy of watching others play, really inspired by Twitch and, you know, co-op gaming, to think of a different type of space where more people could come together and play. And within this setting, representing five different works. So it's a little bit like our VR gallery. There's a menu that people can choose from with some information. There's also volunteers present there that can help you select a work and then play as if you'd have like your console and your different games and you have a group of people and yeah, you can stay as long as you want, stay as many as we have. And yeah, that's something I'm personally really excited for and really also opens up the potential for distribution. You know, it doesn't require really bespoke installations, but still allows for people together and have an experience together.

[00:32:04.401] Kent Bye: Can you just quickly go through the five pieces and maybe just a few words on each of those?

[00:32:11.303] Nina van Doren: Sure. So one and also very much ties into the theme is a piece by Nathalie Lohaerts. It's called Individualism in the Dead Internet Age. Nathalie is really someone that comes from that itch.io, like the really independent game developer, really well known for making games. experimental games interactive zines also creating tools like for other artists and game designers to use such as the zine maker really in the spirit of this early handmade internet like the weird the quirky before everything became sort of optimized and monetized and this piece is really a sort of requiem for that internet for the dead internet really reflecting on like how that sort of once playful open web turned into something that's so now closed and corporate and you know dominated by all this ai slush and you know ads but also it's very much an encouragement and a piece of activism to really you know when we spoke to her as well she's like you know it's really not that hard to make a game you know anyone can do it and learn it to yourself almost as a life skill but learn how to make a website you know reclaim that agency instead of like having to make an instagram page or whatever you know like you can build these things yourself and definitely do so and really claim agency so this piece is beautiful it's a walking sort of simulator as you're You're encountering different sort of nostalgic web elements. And it's also a sort of rant that's against this sort of corporate web. And she's also joining us for a workshop she's doing to give people the tools, like to encourage them, you know, make your own stuff. So that's happening in one of the playrooms this year. And we try to select like five very different type of experiences. You know, this one by Natalie is also it's very much in a tradition of like, you know, an interactive essay or like these type of things that you find in interactive documentary. But we have quite different experiences. Also, a hip hop album, interactive hip hop album called Automotor by Albert Johnson, a.k.a. Rapper Vile. He's both a hip hop artist as well as a creative technologist. And he combined these two passions basically to code and build various 3D environments. That is this music album where you don't just listen to the music, but really go through the sort of song environments that you navigate. And he developed this during a fellowship at the New Museum. It's very much about Chicago, a city that's important to him, to this whole hip-hop culture, you know, so his personal history. There's a lot of references to the digital and the virtual, you know, from early Nilti's web aesthetics. And I think it's such a cool example. You know, artists have for many years been experimenting, of course, with interactive albums since the 90s. I already mentioned Laurie Anderson as one of the people I really admire from an early age on, you know, people like her, but also Björk, you know, Gorillaz and But I think it's really cool that he brought something out, you know, this day and age, it's really a post platform to launch a hip hop album music in this way, really not relying like on the streaming platforms, but sort of like a fuck you to those and really make something that's true to him. And that's really encapsulating all his passions and suits this album, which is also very versatile. Yeah, all sorts of sounds are embedded in his music. So it's Yeah, I think you can see where we're going with this interactive cinema to be a sort of umbrella for many different type of experiences. And I don't know, Casper, if you want to say something about one of the others, Coded Black or Unimaginable Red?

[00:35:53.379] Caspar Sonnen: Yeah, I think with Unimaginable Red is the first version of a new game, an indie game that's being developed that creates a utopian version of Amsterdam Red Light District. So in a sense, they can be off the internet theme in reverse, creating a virtual version of the Amsterdam Red Light area as well. The red light district in Amsterdam is rapidly gentrifying and changing into, let's say, a Disney version of the gritty and very real red light district that it used to be. Sparking a lot of debate within the city about what kind of city do we want to have? What kind of space do we want to have for people? like do we want this to become a museum for tourists of the let's say more uh free and but also criminal and crazy side of amsterdam that uh that we used to have unimaginable red creates a virtual sort of futuristic utopian version of this inviting you to run around and play a game that is a snarky subtle and also quite hilarious commentary on If you know the city a little bit, I think many of our international guests have wandered through the Red Light District at some point in their life. I think it's the thing that we hear the most from international guests. Yeah, I've been to Amsterdam once when I was 18. It's interesting to see how they will experience unimaginable red. And then a completely different piece, Coated Black, is a work that it's about two hours of playing. It's an experience where we're taken along black history, different traumatic, painful sides of the history of black people, from colonialism to slavery to modern day situations. and it's one of those pieces where it's using game engines it's using archival material it's using storytelling the creator is specialized in gothic literature a lot of elements come together here it's not a game it's a deeply moving deeply disturbing experience It combines different eras, different cultural references from the UK, from the United States, and somehow becomes this very solemn and moving experience that in a way, shows, I think, the power of interactive storytelling by allowing, I think you mentioned William Oricchio in your introduction. William Oricchio from MIT, I think, once described it beautifully, the power of interactive storytelling by saying you can have a linear story, which is kind of like going on a tour of a city in an open double-decker bus where you get to be driven like past all the different sites and you see all the highlights of the city. Interactive storytelling is more like wandering. Like you just, without a map, wander through a city and see where you end up. Coded Black, without making you feel lost, really invites you to wander, to see a story at your own pace. And I think that's something that has become quite rare. Like I think the pacing of stories that we experience these days are increasingly force-fed are increasingly formulaic whether it's scrolling going through things way too fast or being seduced into binge watching a series that is great for like the first half season but after a while you kind of feel that they're stretching it to get the most out of this ip and you start to see the formula you start to see the format instead of the content Coated Black really is one of those pieces that really delivers, finds the right form for the right story. This is telling a story that is not a story of today. It's a centuries-old story that is as relevant today as it was 300 years ago. So it's, yeah, it's one of those pieces that we're really proud. It's an artist we didn't know. They submitted to us. This is, I think, what makes the curation that me and Nina do such a joy. to discover an artist and work like this. And then again, as Nina said, to be able to present it in a new experimental presentation form of like a collective interactive cinema. Yeah, it's really something we're excited about this year.

[00:40:18.455] Kent Bye: Nice. What was the fifth piece that's a part of the interactive cinema?

[00:40:22.279] Nina van Doren: That's Gilda Rotha's Tracing Colombia.

[00:40:26.095] Caspar Sonnen: So maybe to end with the fifth piece in the interactive cinema where Coder Black was an artist that we didn't know before, Trace in Colombia is really the return to DocLab of an artist that we featured a number of times in the past. It's Jan Rothuizen, a very well-known visual artist in the Netherlands. He makes... Graphic illustrations is the foundation of his work, but he works across different disciplines. I guess visual artist is probably the most known term for his work. But he's done web documentaries, multimedia pieces. He made one of the first VR projects, hand-drawn VR projects that won our award, I think, 10 years ago or so. And he's back with a very personal travel story this year called Tracing Colombia, which is... kind of his personal journey of discovery visiting the country of Colombia. And really we follow him as the kind of stumbles from discovery to discovery through Bobotá. And in a way, the forum that it became is an interactive web documentary, which is a forum that we saw a lot in the first 10 years of DocLab when the internet was not something that led you to an app store or to a social media platform or to a place to book tickets or book a railroad trip but was a place where people had home pages and people created destinations for others to come and visit we kind of lost that a little bit that's also i think one of the reasons why our theme of the internet this year was something that we by sort of saying get off the internet we're also saying get back to the old internet like where are those websites where are those places that are truly independent handcrafted space online that you could spend time instead of someone's netflix database or spotify database like what about a personal website of an artist we're starting to lose those increasingly and we're starting also to see a counter movement of artists moving and bringing those things back Trace in Colombia is a great example of a format that I think we lost because the industry and artists as well moved to VR and moved to other new innovations or moved to AI or moved to wherever the money was. To a certain extent, web documentary and interactive stories are here to stay. This is one of those projects that... We felt an artist that we know has been working on this for years and brings it back. It's our role as curators to platform these pieces and to also let artists show other artists like what kind of forms you can create.

[00:43:06.137] Kent Bye: Yeah, the hashtag that comes to mind is the hashtag IndieWeb. It's a movement of people trying to go back to the web. And I think about that myself as I have an archive of material and other ways that I could potentially in the future make it more of an interactive experience. It's still mostly just a RSS feed generator and a blog and ways that I can put out my podcast. But yeah, it's something I think around. So I'll be very curious to look at these different examples of interactive cinema.

[00:43:32.878] Caspar Sonnen: Well, I think maybe one of the things that me and Nina stumbled upon while working on the program was Giles Peterson, a musician who created a homepage for his work. Again, like homepage, it sounds like nostalgic saying that out loud, a website. And when launching it on social media, of course, he mentioned something that I think stuck with us a lot. that was that he said like while creating a website of his work a place for people to gather and discover what he's working on he said like yeah i'm used for the past few years to work only on social media where you're basically in a perpetual present like social media is the constant now of what's happening now what's happening right now and it's like by building a website you're also creating an archive of stuff you've done in the past you're also creating a section where people can see what you're working on now things that are not finished yet or things that will be coming in the future and he said like in that sense we kind of lost our history and our future and got stuck in a perpetual presence on social media in the past 10 years and i think that's really really true like i think on a mental psychological level as a species we humans have become so obsessed with the instant now the convenience of it but also the sort of pervasiveness of it that there is no time to look back like the amount of things that we're bookmarking right read for later see later we never return to it both of you now have a beautiful bookcase behind you i think you are people who read those books

[00:45:11.397] Kent Bye: Well, hell, I don't have to be too presumptuous. Well, there you go. It's a lot of aspiration in there.

[00:45:19.644] Caspar Sonnen: But it is something that really started to go through our curational conversations this year when we were thinking, like, looking at different works that really invite us to, like Coded Black, to spend more time in a certain space or in a certain story instead of just moving from one to the next, everything at the same time.

[00:45:39.441] Kent Bye: Cool. Well, you did mention moving from the interactive web into like a lot of monies going into both VR and AI. And so I did want to talk around the VR gallery and the immersive pieces that are featured this year. So I'd love to hear a little bit more context for the different VR work that you're showing this year.

[00:45:56.629] Caspar Sonnen: Maybe a bridge. If we talk about the... the collective experience of the interactive cinema which is something we really appreciate we also really acknowledge in that sense that sometimes what we can see like in the conversations around the immersive arts i think we've had a lot of conversations about headsets being isolating and headsets being awkward because the vr headsets disconnect us from the world around us I think we agree with that criticism in the sense that we can lose ourselves in a form of escapism to a point that we use it to look away from the real world and what's happening around us. At the same time, I think if we look at social media and the perpetual now, everything that's happening in the world is getting to us even though it's in a biased bubble algorithmic curated version we're still getting everything on the same surface level floated in front of us that's doing something to us seeing images of war with images of cooking videos with funny memes all at the same time at the same level has created some quite drastic form of context collapse where we're always on, we're always trying to process everything at the same time, from very nearby to very far away. And there is a meaning, there's a reason why we have physical distance between us. There is a meaning to that. And if that context is gone, we struggle. And we sometimes even struggle to even have a response to things happening. if it's all at the same time on the same level. So when this year we had a piece submitted to us that's Under the Same Sky, which is a citizen journalism, immersive citizen journalism piece made by artists in Syria and journalists in Gaza, we were quite struck by the power of a work that's a 38-minute 360 video. And it basically immerses you in Gaza a little over a year ago when it was filmed. and just allows you to be there. And I think like it's for us, one of the pieces where you really see the power of immersive journalism, something that was very much on the rise in the early days of VR and kind of lost its traction as journalism outlets realized that there was very few people who could actually see immersive works and it was quite expensive and difficult to make. we're now 10 years later and you get to experience 38 minutes inside Gaza something you kind of seen all you know everything about you've seen all the footage float around your feed on the news but really spending 38 minutes isolated away from the world you are in right now in that other space get the story told to you by the people who are living it then and there is really almost i would say almost painful to realize how hard it is to really focus on something like that even with something as important as stories of human suffering unlike we've seen in a long time experiencing something like that without distraction of other stories is really something that we feel is a meaningful experience it's something that actually the isolation of vr actually helps us to in this case keep out some of the other distractions so this is one of the examples where we really feel like the vr gallery vr is a medium also really works as a great way to focus our attention to a single story or a single experience or a single topic which is sometimes refreshingly good to do yeah but and also i think that goes for maybe for some of the other pieces in the art gallery as well right

[00:49:55.307] Nina van Doren: Yeah, no, definitely. I was just going to add also specifically around the topic of Gaza, of course, and this work, the discomfort also, of course, watching this, we are watching it from, you know, the comfort of a safety, even like festival setting. So... it's also about the violence, I think, of looking at self, where you are placed in Gaza, but it's still, you know, virtual reality. And I feel that's, yeah, you're sort of haunting it almost, as if you're sort of floating above this. And to me, that was really striking. Sami Sultan was the the cameraman, you know, he's holding up this 360 camera on a stick, you know, high above his head. And none of this is, of course, polished away, like that's often done in 360 VR. And I think that that raw reality, you know, and their determination to really document something that's going on that we see, like Casper says, so fragmented through the news and, but really, you know, shouting at higher volumes, you know, see what is happening. And also in the piece, you see people filming on their phones and sometimes the images overlaid with screen recordings on social media is showing how everyone is like both documenting but also like drowning in the same circulation of horror so i think yeah really is in the exhibition to give it a space and the attention and to really be able to focus and sit with it i think it's even doing more than that and really confront ourselves with our position where we are in of course like safely floating above

[00:51:25.489] Kent Bye: And what are some of the other pieces that are in the VR gallery?

[00:51:29.637] Nina van Doren: It's hard to make a bridge when talking about this piece, I think, because it was for us, I think it's one of the first ones we've selected. I think there's so much in it, but to make a very sort of maybe hard turn, but to draw a bridge of like how the form of a work can also really inform the tone and like how virtual reality works on many different levels. There's this incredibly endearing piece by Iris van der Meulen, which is a Dutch VR artist who quite new in the scene who's been working for a few years now on this, on this work called the Lesbian Simulator. So very, very different topic. You're invited to step into this like candy colored simulation and it's very tongue in cheek. That's why I'm saying like, it's very cartoon-esque, like it's very tongue in cheek and you witness a series of formative moments in a queer life. Like you create your own lesbian avatar and you You experience confronting situations in sort of lighthearted, comical way. And we had a lot of really interesting discussions on this. It's like, of course, like a queer life or like the experience of coming out must have been complicated. But I think to say the least, like maybe even traumatic or there's of course lots to say about this. But I think here the form is also very cleverly used. It's really this effective view called deliberately exaggerating, you know, this stylized mode of that treats the serious as sort of playful or ironic. And I think that that sort of queer optimism that really insists on joy and hope is really what makes this piece really delightful. It's funny, it's interactive. You have to scream, I am gay throughout the whole exhibition. It's a really, really, really great piece. It's also been selected, like every year we try to make bridges, of course, with the film program of IDFA and the lesbian simulator has also been selected in one of the youth programs, which is now called Current Future. I have to say it right. It's the new name of IDFA's youth program.

[00:53:32.165] Kent Bye: Nice. And how many other pieces were in the VR gallery?

[00:53:34.728] Nina van Doren: I think there's four or six, but I think there's one more work that's in selection and then we have a couple of spotlight titles. But maybe we can mention Martin Isaac de Heer has returned. We've shown work by him before. dancing with dead animals. And he is now returning with We Are Dead Animals, which very much builds on this world he created before. This is an interactive VR piece. And Maarten Isaac de Heer is a well-known Dutch animator who for many years now has taken the hobby of collecting dead animals that he finds near his studio and then 3D scans them and brings them back to life. So it brings them back to life in virtual reality. taking the word animation quite literally. And the result is that these sort of mangled dead animals are sort of frolicking about in Martin's idea of paradise. In, I think it was 2022, he created a full dome piece of his idea of paradise. And in this interactive VR piece, you really get to workshop with these animals. So you can reassemble them, take them apart. It's really kind of macabre in the most endearing way. It's sort of a love child of the artist Tinkerbell and Lars von Trier or something. And it's really a testimony of a unique artist and an incredible creative piece.

[00:55:02.830] Kent Bye: Nice. Maybe if we stick with the getting through the competition, is there any other VR pieces in competition?

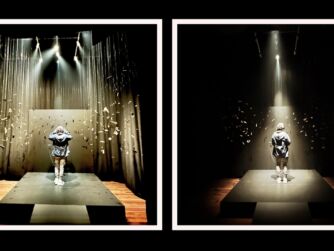

[00:55:11.069] Caspar Sonnen: There is Feedback VR, which I think is a nice one to mention. It's also featured in the VR gallery, but also featured in the Dome program, thanks to the special full Dome version that Collective Amixer, CloudX, and Avinash Chandha from WeMakeVR made for us this year. Feedback VR is a project by Collective Amixer and CloudX Fana 6. who we've been featuring works from in the past as well. They are really leading the immersive scene in Peru, but also much wider working both inside and outside of Peru as a collective and also individually. And Feedback, I think the tagline is an anti-futurist musical. And in many ways, Feedback VR was also one of the first pieces that we selected this year. And one that really was part of the works that inspired the theme a little bit this year. What Feedback VR in a less literal sense, but really in an evocative way shows us, it's a VR film that starts in real life with real life footage, then moves into some sort of avatar digital space. starts weird and intriguing turns nightmarishly joyous outrageous and ends up back in the physical world again and kind of serves as a metaphor in many ways the past 20 years that we've gone through and it shows us how both in a hyper local situation each of our own cultures has also lost something right like if we think about how digital technology not just detached us a little bit from our physical realities it also detached us a little bit from the places nearer to us like we ended up if i mean even if you look at like i don't in the netherlands before there was facebook and the american platforms that we are now part of there was a dutch version of social media That's how we started. The Mixer Collective, their name even refers to the Peruvian social media platform that emerged back in the day. We can even see how 20 years down the line, we're all in the same five platforms together. That's where everything happens. There is no more, sorry to say this to an American person, but we don't have that much of a local technology space anymore. We do, but it's all connected to the bigger platforms in the US and China. It's in that sense, we've also lost some kind of local technology version. And I think feedback VR, even though it doesn't explain or say anything other than really make you feel something, it does create an experience where you're starting to realize what is this feedback loop that we entered into of all becoming part of that same digitized space where every pixel is equal and there is no distance anymore. There is no... Nothing is more special than the other. It's all the same, same, same. To us, feedback VR really was one of those experiences where everything we were thinking about kind of became in a very metaphorical, performative way became apparent. So this is one of the pieces where, yeah, we're really happy to have them with us again this year to present this. And it's going to be an interesting thing to... be able at the festival to both go to the VR gallery and see the individual experience in a headset and compare that to going to the planetarium and see that experience together with 300 people in a giant full-on planetarium.

[00:58:59.997] Kent Bye: Yeah, and this year, like previous years, you're going back to the planetarium where there's going to be five different pieces that are showing there, and three of them are also a part of the immersive competition and translating and creating different forms. I know the Lumbotopia may have been actually... The dome version was in competition, but sometimes it's more of an experiment to see how you can translate some of these immersive pieces into a dome context. And there's two types of domes. One is like you look up and you see the image that's kind of like the half dome. And then there's also the forward facing dome, which we've seen a lot with Cosm and the sphere where you're an audience looking forward at the dome. And so it's a little bit different orientation where it's kind of a different slice of a 360 video per se. But the other couple of pieces that are going to also have dome versions are Reality Looks Back as well as The Rift. I don't know if you want to have anything else you want to say about those other two pieces.

[00:59:54.035] Caspar Sonnen: Maybe Nina, as you've been doing most of the heavy listing on the Planetarium this year to get away all from that version. Maybe you can go into those.

[01:00:01.983] Nina van Doren: Yeah, this year we have the great pleasure of co-curating the program with Diversion Cinema and Paul Bouchard. We are co-presenting this as well. And we have two different evenings where we present these works. And one of them is Reality Looks Back by Anna Jeppesen and Omid Saray. And they are also known for creating earlier VR work. Specifically, A Vocal Landscape is quite well known. And also in A Vocal Landscape is really this intimate, more contemplative work that's linking the personal with really the cosmic. And their new piece also really seems to continue on that thread. It revolves around quantum mechanics. and how something deeply abstract like that can be expressed through everyday moments. It unfolds as a conversation between An and Omid. It's kind of like a late night type of exchange between friends, reflecting on science, philosophizing. And it's really warm and human and really draws something so abstract as quantum mechanics down to Earth, which happens also to be the title of the evening of the planetarium screening this year, Down to Earth. Yeah, really make it feel grounded and personal. And initially when we encountered this piece, it was just only the audio. This conversation between Ann and Omid, and it already worked so beautifully just as this piece of storytelling that's really well structured and really takes you along. But then for the first time, them working in full dome, adding incredible visuals to accompany the story and sort of let you dream along. And I think, yeah, the planetarium is really the perfect space for this work that's built to really look outward at the universe. But here comes the space for turning inward, for reflection and connection. And the rift is a work by Janira Najera, by Matthew Wright. and produced together with Siza Amukwedini, so UK Zimbabwe collaboration. And we spoke to them and heard a little bit more background and it was made under incredibly challenging circumstances, really tight turnaround and the things they had to do but you wouldn't say when you see this piece it's really the result is such a spectacular piece that really like you say it makes use of the really omnidirectional use of this specific dome so you can see it really 360 or all around and that's Janire from 4Pi they're really experts in full dome production so it's super cool for us to see them joining forces with someone like Siza who is this key figure, like really influential advocate for XR production in Zimbabwe. She has this Matamba film labs for women in which she offers training and equipment and access, mentorship and production opportunities specifically for women in Zimbabwe in film, animation and immersive media. So it's a short, very powerful work. It's a choreography of dance, music, there's fashion. It's really telling a story on climate change with a central role for water, like as the connector of all things. So it's, yeah, you see all different disciplines coming together. It's, yeah, it's quite spectacular. Yeah.

[01:03:15.148] Kent Bye: Yeah, and I know with AI, there's a lot of discussions around the role of AI, what it's going to be doing to expand out and kind of blur the lines between what humans are doing, what AI is doing. And so this piece, the Oracle Ritual for the Future for Humans and Non-Humans, I'd love to hear any comments on the Oracle.

[01:03:34.949] Caspar Sonnen: I think if we look at the theme of AI or the hype around AI or whatever we want to call it, I think increasingly people are starting to mention that we're the... What is it? The Oracle? No, well, that around AI that we're sort of in the last... two years of the AI hype and that if it doesn't deliver, if it doesn't return on its investments, we're going to see a lot less of it. Or it's going to eat its own tail by producing so much AI that the quality of AI is just going to go down and down and down. But it is in that sense, one of the conversations that we're all having. So if we look at AI as a theme within the program, there's three works that really directly or indirectly use or tackle or deal with AI. The Oracle is probably the most all-encompassing or the most immersive one. It's an immersive performance, an immersive theatrical experience that brings eight people together in one big immersive space. There's a flying drone. There is AI processing the audience. There is a story that's a very touching and real story. nonfiction story dealing with loss, dealing with bringing people, extending a memory of somebody through technology. And I think it's a performance piece that is one of the most moving ones that we've experienced this year. And it's one that I think very cleverly solves an issue that a lot of AI projects have had in the last couple of years. And that is that the technology has been developing so fast that sometimes the trick of the technology gets more to the forefront and starts to get in the way of the actual thing that the artist wants to say. that you experience the piece and go like oh that's weird or that's great but you're actually just seeing the power of a certain ai plug-in tool and if you've seen it once you've seen it twice kind of what we had in the beginning of vr like oh i've done a roller coaster video in vr well if you've done three roller coaster videos in vr you kind of don't get that same physical response anymore So with AI, when things are going so fast, how do you make sure your piece is still impressive three years down the line when the technology has become more known to everybody or more experienced by everybody? The Oracle really does this in a beautiful way by actually, I mean, small spoiler alert, but there's a moment when the AI content that it shows is different generations of the same AI tool over time. And you start to see, literally you're watching how the AI has developed over the years. And it's not necessarily been getting better. It's been getting more visually impressive. but not necessarily more real and that's something that i found really moving watching the experience to not just clever by the artist like hey you're acknowledging that this is a technology that's in development and you're making that part of the experience but you're also really allowing me to see like the different layers of the technology or the different outputs or the different results of it So it really is one of the more moving pieces in the program. Also one that unfortunately is hard to get into with only eight people per show. Two other pieces that deal with AI, I think one is deep soup, which is almost a response against AI. It's by Luna Maurer and Roel Waters. We're part of the opening night of DocLab when we had our phenomenal friction theme in 2023. Luna and Roel have been diving deep into the meaning of friction as a response against the sort of death by convenience by the seamlessness that technology has brought to our experience of reality where everything is instant and available where we no longer have to have an awkward conversation with our cab driver we can just interact through an app and don't even have to think about tipping or like it's all simple we don't have to oh we can watch where they're going all that seamlessness has also basically been removing friction Without friction, there is no movement. We all need friction to actually have meaningful interactions and experiences. And Deep Soup is kind of their way of celebrating that by inviting the audience as we speak to submit little films that they can make themselves and throw it into this big thing called Deep Soup. a program or project that in the end becomes a film that will premiere during the festival that celebrates all these little physical moments, tangible moments of friction, of awkward interaction that we have been erasing from our experience in the last couple of years. But if we return and celebrate those, what it feels to touch another surface or to, instead of just clicking on it, and in that sense it's also a project that goes back to an older part of the internet where we had these lovely weird art experiments where whether it was with miranda july or with other artists where we were invited as an audience to contribute something to contribute something meaningful and create something bigger together like a chain letter or all these different things A lot of that has been sort of removed and turned into forms and online polling systems in our WhatsApp group messages. But there is this message in a bottle type artwork that is frictionful, that is cumbersome, that is not easy, but it actually requires something of you to contribute and then collectively create something that's bigger than what a single artist could create. deep soup really is a celebration of that older form of community art and uh yeah we look forward to uh celebrating the premiere of the film together with everybody who contributed and the wider festival audience during the festival and we're actually screening that film as a short film, also together with Mark Isaac's Synthetic Sincerity, which is a traditional linear documentary exploring AI in a completely different way. But definitely a tip for those who are not as familiar with the documentary filmmaking community. Mark Isaacs is one of the great documentary filmmakers working today. So that's a nice way as well to see where the immersive program of IDFA interacts with the regular film program of IDFA. And maybe the third project that deals with AI is Artificial Sex by Anand Vries. Maybe Nina, you want to...

[01:10:28.820] Nina van Doren: Yeah, like you're talking about seamlessness and friction, I think. Anand is really someone that points at those seams or maybe rather even rips them open. It's a fantastic new work. We've shown work by Anand before, a virtual reality piece called Post-Human Wounds, together with Malou Peters, where they questioned what pregnancy could look like beyond the normative and stereotypical. And across their practice, they really push back against this idea, you know, that nature should dictate how we live or define gender. And, yeah, very much reminding us that what we call natural is often used to justify oppression. You know, like women are naturally nurturing or men are naturally rational. And artificial sex very much also talks about this. It's about relationships, essentially. They explore relationships with AI bots, which is very current, of course, today, you know, as more and more people turn to AI also for companionship, for love. You know, we all know these stories of people falling in love with bots. or simply just to play out fantasies. And they're centering this around an interactive video installation. There's touching sensors that trigger two intimate video conversations between Anon and different AI companions that they created. So it's a bit of a mix of a sort of post-human pillow talk with the desktop diary or like screen performance. So you get a glimpse into the desktop of Anand and the software they use to create these AI companions. And with these AI lovers, they discuss AI-generated pornography, which at the moment turns out is fairly full of bizarre glitches as the AI is still struggling to get the bodies right. It doesn't really... gets what sex is. Anand collected an incredible amount of these images that was AI generated, like there's nipples on bums, there's extra limbs, like impossible anatomies. But the great thing about this piece that Anand really saw a lot of potential in these glitches as a type of raw material almost for rethinking gender and genitalia and what intimacy could be. And yeah, it's kind of like a unique moment in time as these glitches will probably be polished away quite quickly. So I think the seams that they're pointing at is like AI is training, of course, on existing pornography, which is very, very much sexist, heteronormative, and, you know, it's submissive female tropes and other stereotypes. And I think that's great about, you know, Anana really fits in their longer practice of, you sort of xenofeminist embracing the alien, the artificial as a way to kind of escape old gender scripts. So they're celebrating these weird forms that AI is coming up with and even 3D printed some of these like genitalia that they came up with and as audiences are invited to hold and touch and admire. So yeah, not rejecting AI or technology, but really hijacked them and to imagine new, weirder, freer, queer forms of intimacy.

[01:13:35.501] Kent Bye: Nice. Well, we've got three more pieces in competition if we cover and then we can start to wrap up. So the last piece in the immersive nonfiction competition is called N36,000 Ways, a site-specific installation. Maybe just a few words about that.

[01:13:49.582] Caspar Sonnen: yeah 36 000 ways i think we mentioned uh under the same sky as one of the more striking immersive journalism pieces in the selection 36 000 ways is a piece that is created by karim ben khalifa who started his career as a war photographer and who many in the immersive world know from the early days because he made one of the landmark immersive pieces called the enemy which was a project that used VR, one of the first fully metric interactive VR pieces that allowed you to stand in between two opposing protagonists from well-known conflicts across the world. And Karim has moved, I think, from discipline to discipline. And it's really interesting to see how now he's bringing us in 36,000 ways, which is A very physical and biometric installation that combines shrapnel that he's been collecting in the battlefields in Ukraine. And the title refers to modern day bombs that explode in up to 36,000 pieces of razor sharp shrapnel. And this is not just a crude bomb. This is high tech. This is algorithmically designed modern day warfare tools that are created to explode in as many razor sharp pieces as possible. Because this is the most efficient way to basically kill human beings where the bombs are dropped. The installation is a first version of it where the audience is invited to stand inside a space surrounded by different pieces of shrapnel as a biometric camera traces their heartbeat and plays it back within the installation, kind of combining these physical symbols of death and destruction and combining it with the most vulnerable sign of life, listening to someone's heartbeat. It's an example of immersive storytelling using our human bodies, something that I think we really appreciate as an underdeveloped part of the immersive art field. I think if we think about off the internet, funnily enough, a lot of tech art and a lot of immersive experiences are a great way to actually help us reconnect with our physicality, to reconnect with our bodies. This is one of those pieces that invites us to step outside of our mental experience of the world, to step outside of just the visual, but really to start embodying space and feel what it is to be next to physical objects. So yeah, this is a first version of what will become a larger, more kinetic installation in the future. So it's also a way for us to allow the artists to see how it works in this first version to see where it develops in the future.

[01:16:56.722] Kent Bye: All right. So as we start to wrap up the DocLab competition for digital storytelling, there's two more pieces. Let's go to the gamer keyboard wall piece number two.

[01:17:07.093] Nina van Doren: That's a piece by Chef Van Beers, a Dutch artist who's been presenting really incredible work, often hacking sort of consumer devices. In this work, he hacked different gamer keyboards, the ones with the colorful lights. I think we all have an image of them. As a sort of quintessential product for a gamer, Chef loves sort of researching digital culture and specifically maybe the alt-right, like the manosphere, a lot of like dynamics of Gamergate. But in the gamer keyboard wall piece, he's essentially using this as a way to display different texts, texts that are stemming from his research on online culture, specifically online masculinity or toxic masculinity, the alt-rights. And also counter positioning this with some online feminism. You can read from a distance. It's a beautiful wall piece. So it's really a beautiful gallery type of work showing different texts, introducing us to different main discourses that are happening online.