Alex Chu is an Interaction Designer at Samsung Research America, and he talks about the process and insights that came from designing Milk VR 360-degree video player for the Samsung Gear VR that’s powered by Oculus.

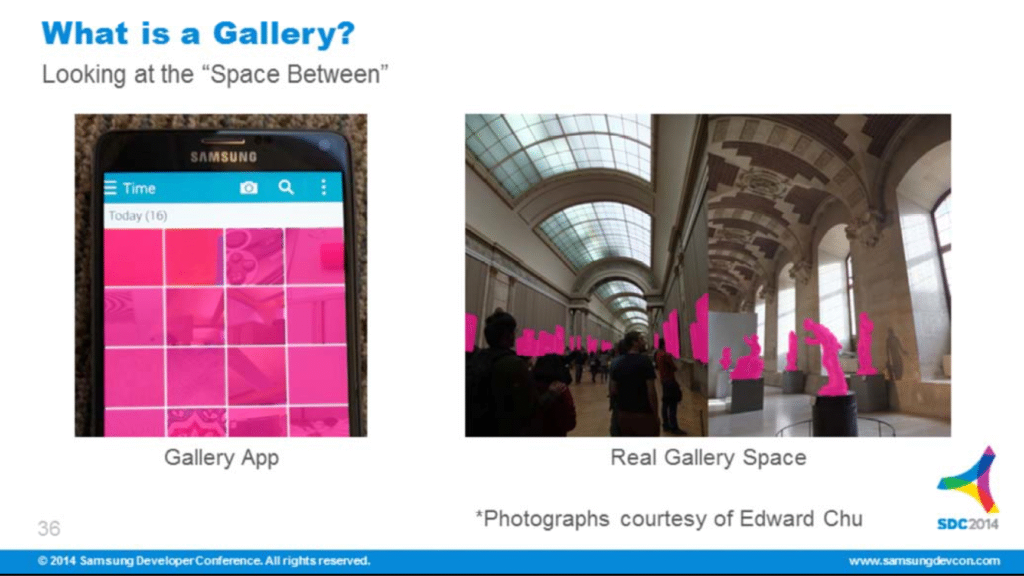

He talks about the importance of space when designing for virtual reality experiences, which he sees as a blend between real space and digital space. The Gear VR prototype team had been designing for mobile apps, and it took them some time to realize the importance of adding an environment and putting in architectural space around the content to help define the surrounding environment. For example, here’s a comparison that shows the difference between a gallery in 2D space vs designing a gallery for a 3D space and in VR:

At the Samsung Developer Conference, Alex gave a talk titled:

VR Design: Transitioning from a 2D to a 3D Design Paradigm. He gave an abbreviated version of this talk at the Immersive Technology Alliance meeting at GDC, but you can see the full presentation slides here.

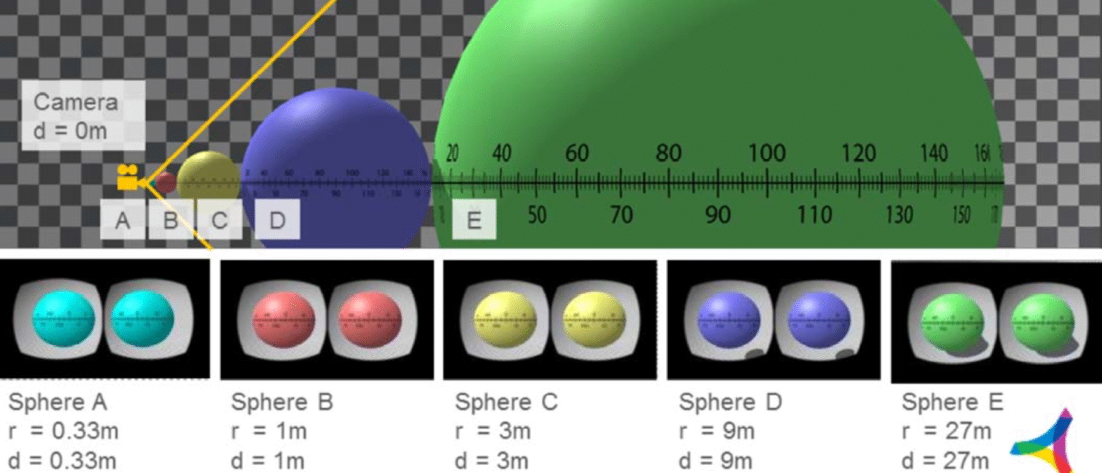

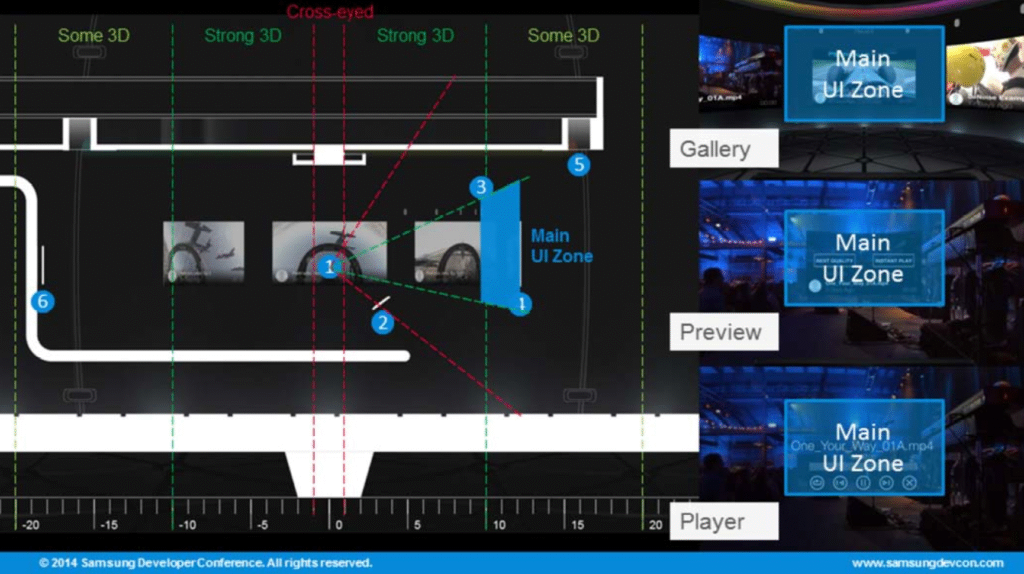

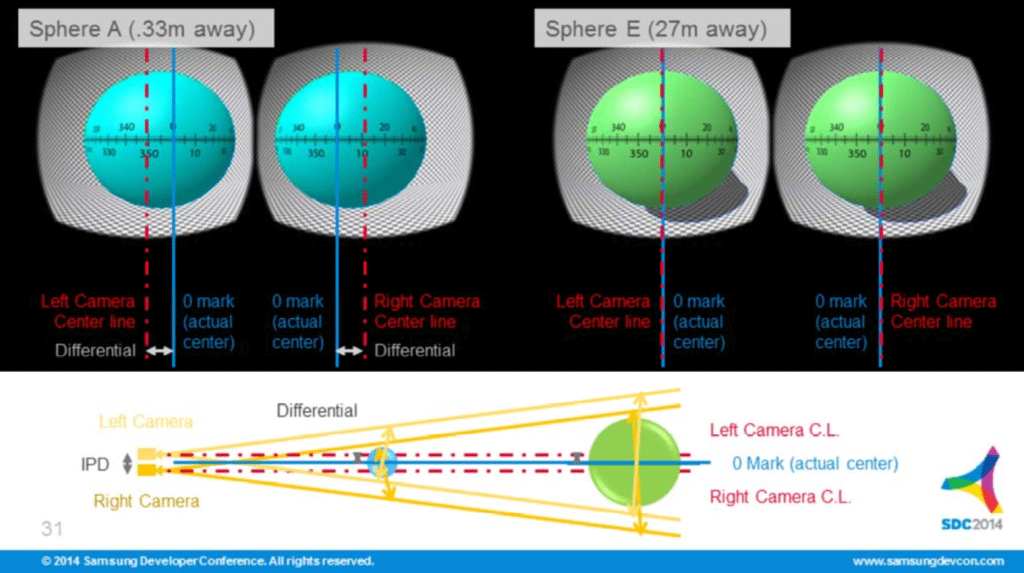

Alex showed a number of different ergonomic graphics showing about how users engage with content and giving metrics for comfortable ranges for the user. They also researched Field of View in order to help determine how to size their elements, as well as using peripheral vision to help guide their eyes. Finally, they also looked at depth cues and the range of visual disparity at different distances to see how the strength of stereoscopic cues varies depending on the depth. Here’s a number of slides with more info:

He also talks about the user interaction options for a Gear VR, and why they decided that having a physical tap interaction paradigm was more reactive than just a gaze and wait type of interaction.

Some of the advice that Alex gives about user testing is to make your test meaningful by focusing on something very specific, and to eliminate all of the other variables that you’re not trying to test.

One of the biggest open problems with designing for VR is that there’s a huge range of how people react to VR experiences, and it’ll take some time for everyone to learn more about these differences and share data about how to best design for everyone.

Finally, Alex sees that the sky is the limit for designing for VR right now, and that he’s really looking forward to seeing how using architectural representations in VR will change the process of designing physical spaces.

Theme music: “Fatality” by Tigoolio

Subscribe to the Voices of VR podcast.

You can watch Alex’s full presentation from the Samsung Developer conference here:

Here’s a YouTube playlist of all of the VR-related presentations from the Samsung Developer Conference.

Rough Transcript

[00:00:05.452] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR Podcast.

[00:00:12.214] Alex Chu: My name's Alex Chu. I'm lead designer for VR stuff at Samsung Research America out of Dallas. We helped put together some of the original prototypes for the Gear VR, both the hardware drop-in and then some of the software that was running on mobile. You might have heard Carmack mention that in his speech today. We're that research group in Dallas that worked on that stuff. And currently, we're actually the team. One of those original prototypes ended up turning into MilkVR. So it was a 360 video player that we ended up making into a 360 video service. And it's one of those apps that exist on the Gear VR where you can actually continue to get used beyond sort of that two-minute experience that a lot of people have because we're continuously updating it with new content. So we have everything from 2D 360 videos to 3D 360 videos and are continuing to release new content. So I worked on the interface and then some of the ideas that went into the whole sort of project in the first place.

[00:01:17.750] Kent Bye: Nice. And so there was the Immersive Technology Association meeting this morning and you gave a little talk about some of the lessons that you learned from designing MilkVR at Samsung. And one of the things that I found really interesting was the consideration of space. And so maybe talk about that evolution of doing different iterations and kind of realizing the importance of space and environment.

[00:01:37.760] Alex Chu: Sure, I think, you know, the concept of space is something that, you know, although we deal with it every day, there's sort of different types of space that we interact with. So, you know, there's the real space, sort of buildings and my body and the way that I interact with the world. But there's also the space of two dimensional digital experiences. So things like, you know, playing around with your phone and playing on a computer and those types of experiences. And I think VR is really its own sort of third category of space where it's not quite, you know, the real space that we inhabit. It's not quite the digital space, but it's something that's sort of blended in between. And the exact mix of what that is depends on the developer and what they want to engage with. So you could see you know, AR is probably on one end of that spectrum, whereas there's some experiences where maybe it's just, you know, a cinema, and so you're still essentially looking at, like, a 2D interface. And I think that VR space is really whatever you want to make it, and there's a lot of potential there, but you really have to sort of consider that engagement and really think about space directly and critically to get that balance right and to get the performance that you want for that type of space.

[00:02:52.919] Kent Bye: Yeah, one of the things that I found really interesting was that you gave sort of a first iteration where you just had a bunch of icons with text, but not a lot of depth or consideration for the wider environment that you're in. And then the eventual one that you end up shipping with MilkVR has much more of a sense that you're in this whole 3D space. So maybe talk about that process of discovering the importance of to kind of really flesh out a 3D area.

[00:03:18.835] Alex Chu: Sure, yeah. I think when we first started the project, we were really approaching it like we approach any of our other mobile projects. So our group had been working on the implementation for the Galaxy home screen and, you know, we did the LeBron app, we did a number of other mobile experiences. And so we were really coming from that background and our design best practices at the time Revolved around sort of making content the center of focus There really shouldn't be any elements other than the actual content that you're trying to show off And what we realized over time was that you know VR is a space you're actually inhabiting it and it's a large space It's enveloping you all the way around and so I think certain things about having the content almost like eclipse the idea of environment in a 2D digital experience. In a 3D virtual reality experience, you have so much of this space that content can play a very different role. And so I think in the iteration that we ended up with, You know, the content is still king, but it has to take place in an environment that feels right, that feels like a space that you could actually inhabit and be comfortable inhabiting. So that meant, you know, putting in pieces of architecture, treating those pieces with a material quality that defined the environment that we were creating.

[00:04:41.057] Kent Bye: Yeah, and it seems like doing design within virtual reality spaces is sort of the Wild West in some ways. You showed a number of different graphs with different charts and bars and everything, and maybe you could sort of describe what some of those charts and graphs were trying to say.

[00:04:56.366] Alex Chu: Yeah, sure. I think... You know, any good designer that you talk to will talk about ergonomics because it's really about how the user interacts with content given a certain platform. Like, you know, in mobile, you can think about, well, where is the person going to be holding this device and how is their thumb or, you know, in the case of a note, like a pen, going to be interacting with that content. And designers are very smart about doing research into how that user is going to be engaging the content. I think we have to do the same thing for VR. So, some of the charts that we showed was looking at, for example, what is a comfortable range for a person if they have to look at the items that they're going to be interacting with, they're really using their head and their neck to do that selection. So, we have to make sure as designers that we're taking that into consideration. So, we want to create a comfortable experience where you're not always looking down to you know, interact with something on the floor, always looking up. You know, we want to put things in a comfortable range if they're going to be used a lot. So that was one of the things we looked at. The other one was field of view. So you'll probably hear a lot of people talk about how when you actually see in VR, you're really only focused on a very small area in front of you, and then the rest of the view really becomes peripheral. So when sizing our UI elements, we wanted to make sure that one element fit comfortably into that field of view that was going to be in focus. And at the same time, we used the peripheral field of view to guide the eye. And we have this breadcrumb trail of thumbnails going in a carousel around you. And so even though you can be focused on one, you'll always have the sense of whether there's one to the right or one to the left. And then finally, we did some studies looking at depth and how you perceive depth, which is a really important part of VR. And some of the things that we learned was that beyond a certain point, you can't really tell. You know, there's no stereo disparity, which means that your right eye and your left eye are seeing basically exactly the same thing. Whereas when something's closer than a certain range, your right and left eye will be seeing different sides of that object. And so that can actually help you determine where you put your 3D geometry so that you're really using that geometry to its greatest effect. And there's been a lot of interesting work being done to look at how can we optimize that even further by potentially rendering certain things monoscopically and then the things that need to be stereoscopic stereoscopic. Just one final note, there's actually a range where things can get too close and your eye can begin to sort of fight between sort of the near object and the far object. So you want to avoid those conflicts. So I think really all that data is what we used basically to just ensure that what we were designing was going to be comfortable for users. And I think it's just good practice. Most designers, I think, will agree with me.

[00:07:54.232] Kent Bye: And so depth is something that design in a 2D plane hasn't really been able to use that much. And so what were some of the insights that you got for how are you actually using depth in terms of a user interface or user interaction?

[00:08:07.570] Alex Chu: Yeah, that's an interesting question. I think, you know, it did sort of affect the way that we were placing thumbnails. So we have some interactive objects are placed at a certain depth where, you know, they'll still feel comfortable, but they will be using that stereo disparity. So they will sort of feel three dimensional. And some of our selection methods will actually sort of, instead of a highlight state where it actually lights up, we'll have it sort of move forward a little bit. And that's one of the nice things about playing with VR space is that it gives you sort of this third dimension that you can really start to use for impactful interactions in this space. But you can also overdo it as well. So, you know, we had to sort of walk a fine line and we definitely had lots of experiments that failed for some reason or another because they just didn't feel right or it caused weird interaction in the scene or something. So depth is great. It's having another tool in your kit that you can play with, but just use it wisely.

[00:09:04.265] Kent Bye: Yeah, in terms of the input, you mentioned that there's gazed input and also a controller, and there's also a slide pad on the side. Given those inputs, how did that impact what type of user interfaces that you could design?

[00:09:18.361] Alex Chu: Yeah, I think that's a good question. So as I mentioned in my talk, we really wanted this to be a mobile experience, which meant that it had to be portable. And I think the idea of having a touchpad on the side of the device was really important to that, because you're never going to lose your ability to interact with something, even if it's at a basic level. We did a couple experiments early on when we didn't actually have the input device and tried things like, you know, just a timer based on looking at something and then counting up, you know, one, two, three seconds and then that counts as a tap. But really it didn't have the immediacy of the touchpad, you know, the way it works now. And I think that, you know, building off of that input and always being able to count on that, did lead to sort of the interaction paradigm that you mentioned, which is gaze-based. So you can look at something and tap in order to select it. We have basic gestures like swipe, you know, panning up and down. Right now it was only a single input, so you get a touchdown event. So you can't do things like pinch to zoom. But I think that input device did define what is the main interaction paradigm. And then I think Oculus also made that sort of more concrete by including that in the first run tutorial that happens. When you first plug in your gear, it'll actually walk you through those basic paradigms. And so in that way, that basic interaction language gets made part of the Oculus platform.

[00:10:48.328] Kent Bye: Is there anything that you experimented with that just did not work at all and that you would not recommend people try?

[00:10:54.770] Alex Chu: So I think one of the things that I always have issue with is if you tie the head motion also to be an input for some other kind of translation or rotation, it becomes a little bit troublesome because I think people's initial instinct is to look around. And if somehow like tilting my head is also going to be moving me, you can start to get a lot of different forces that feel very unnatural to a person because you know in regular real space I can look around and it doesn't affect which way I'm translating or if I'm moving left or right. So I think that's definitely one thing that feels good on paper but may not be so good in execution. So another one is maybe If you sort of look up and then cause something to maybe pan down, or if looking left will auto scroll something, it's sort of a conflict of senses. So again, you're not really used to having the world react. You know, by me looking left, it doesn't cause like a bunch of stuff to move right. So I think that's another one that, you know, on paper or on a whiteboard, it seems like a great idea, but in practice, it doesn't actually end up working.

[00:12:07.067] Kent Bye: Yeah. And I think the people's sensitivities to motion sickness, especially when they start to do things like that, where you're kind of making it more pronounced than they would expect in real life. And so that sort of brings up to the question of like doing user testing and, you know, maybe you build up a certain tolerance. What was the process like of sort of making these prototypes and actually putting it and testing it with new users and what type of feedback you got from that process?

[00:12:31.465] Alex Chu: Yeah, I think the key with user testing is to try not to spend more time than you need to building the prototype, because it could very well turn out to be a bad idea. So you really have to reduce the tests that you're going to do to isolate exactly what it is that you want to test. And so I've seen people do tests that You know, it's just kind of qualitatively like, oh, this was great versus that one, which is not very good. But you really want to sort of make your test meaningful. And that means, I think, being very focused on exactly what it is that you want to test, build something that tests just that, and remove every other variable so that you can clearly say that the reason that this test came out this way was because of the thing that I'm testing. And so, yeah, I guess that's just from a high level.

[00:13:17.171] Kent Bye: Yeah, and going through that process, I imagine that you had come to a number of different best practices in terms of what works really well. And maybe you could, at a high level, deconstruct some of the interface design decisions that you made within MilkVR based upon some of those best practices that you discovered through this process.

[00:13:34.165] Alex Chu: Sure, I mean, I think, like I mentioned, it all depends on what type of interaction you want the person to be doing, and then also the rules for the environment that you set up. So, in one person's game, there might be a rule that, you know, you can actually move around as a person, depending on the technology, and in another person's, they might be using the gaze-based tracking, and so I can really only speak to you know, the experiences that we had, which was mainly using the gaze-based interface. And that is to put things in a comfortable zone so it actually ends up being a lot smaller than you might think. And yeah, just taking that ergonomic data into account so people can sort of comfortably look right or left, you know, about 30 degrees in either direction. Looking down for long periods of time, I think the headset can start to sort of weigh on the back of your neck if you have somebody consistently looking down at a sharp angle, so I've tried to avoid that. Looking up is great because I think then the headset starts to sort of rest on your face a little bit better. So there's no real problems there. And then you don't want to put things too close if you have stuff further back. So if you get closer than about a meter, your eyes are going to be trying to converge on an object that's close. And your brain is going to be trying to basically create a single object out of two different images. But it's going to potentially be conflicting with what you're seeing in a far field. So you really want to avoid putting objects too close. And then there's just general best practices about your body is very sensitive to acceleration. So if you're putting someone in an environment where they're accelerating really quickly or changing acceleration direction, they'll be able to feel in their body that that's not actually happening. And so that can cause some issues with simulator sickness. So in general, you just want to keep things slow and keep things comfortable and just be conscious of the user on the other end of that experience.

[00:15:35.613] Kent Bye: What would you say are some of the biggest open problems when it comes to doing 3D user interfaces or user experiences within virtual reality?

[00:15:45.439] Alex Chu: So I think one of the biggest problems is just that everyone's different. Our bodies vary a lot from person to person. especially when it comes to things like perception. And that's something that's really key to VR. So I can say that, you know, most people's hands, even though they might be sized differently, they're fundamentally have like the same sort of range of motion. But when it comes to perception, some people will be much more sensitive to getting, you know, motion sickness than others. The IPD distance is sort of always different with everybody. Yeah, just accounting for all of the different types of people out there is a big problem that needs to be solved. And I guess it's not really a problem, it's just an idea about getting enough data that you can comfortably make decisions. And that's something that hopefully we can do as a VR community together. And I think people need to sort of publish what they learn or talk about it so that we as a community can grow together.

[00:16:43.023] Kent Bye: And finally, what do you see as the ultimate potential for virtual reality and what it can enable?

[00:16:49.461] Alex Chu: Oh, man. Yeah, I don't know. I mean, sky's the limit, I think. The technology is constantly sort of outpacing what we know what to do with it, I think, still, which is a great place to be where, basically, if you can imagine doing it, you can try it out in VR right now. Yeah, I think we're going to have to leave that one an open question. Basically, it's as big as you can imagine. I think you should be able to start trying to do that.

[00:17:16.046] Kent Bye: Are there any experiences that you really want to have in VR?

[00:17:19.307] Alex Chu: Yeah, so I guess on a personal level, I come from an architectural background, so I did architectural education. I worked as an architect for a while. And I've always wanted to have really good architectural representations. I think making that part of your workflow as an architect could be really powerful because, you know, you almost never really get to see what your project is going to look like until it's built. And experience can help you envision that. But I think VR could play an amazing role in that process of design, because it actually could give you a glimpse of what inhabiting that space might be like. Whereas nowadays, you really have to sort of build a model, and it's sort of an analogy to what you could get. But we can get much closer in VR. So I'd love to see somebody take that project on.

[00:18:08.571] Kent Bye: Great. Well, thank you.

[00:18:09.732] Alex Chu: Yeah, thank you very much. This was great.