I speak with visual artist Elizabeth Honer who uses Open Brush to pain her dreams as well as with Martha Crawford who leads dream workshops. See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Rough Transcript

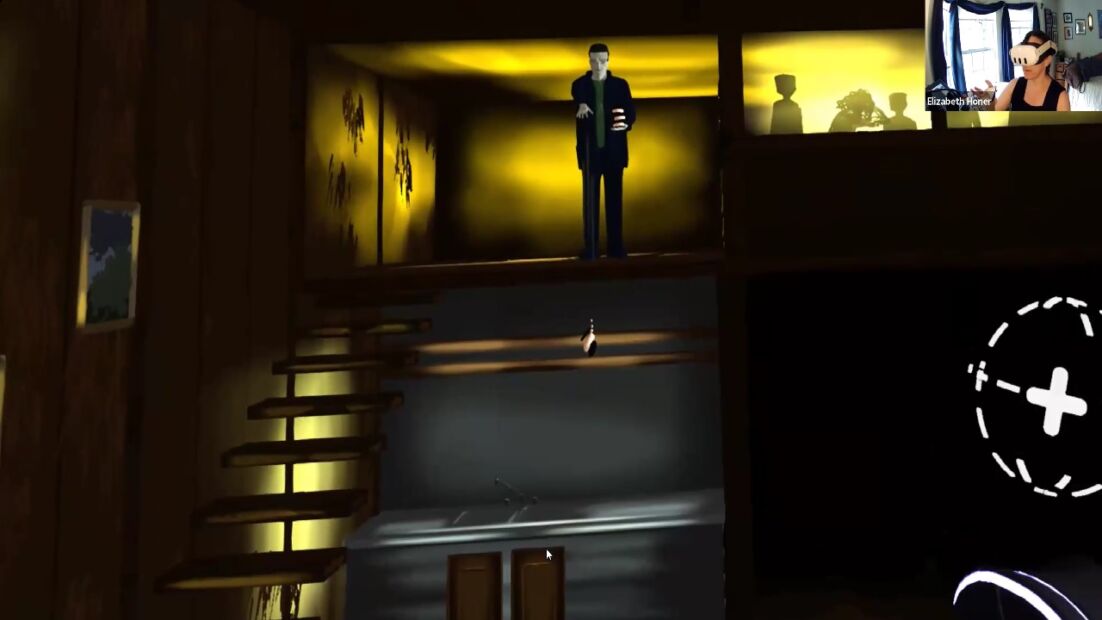

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR Podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR Podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So I'm going to be wrapping up my immersive storytelling Tribeca ConXR and immersive storytelling events that are happening at Onassis Onyx Summer Showcase. With a conversation that I did about dreams and dream work, if you notice, there's a lot of the immersive artworks that start to deploy what I refer to as dream logic or magical realism, where it feels like you're walking into somebody's dream. And there's been a number of different projects over the years that have deployed this type of dream logic. Singing Shens, The Man Who Couldn't Leave, also Celine Damon with Songs for a Passerby, Body Lisp from Shen Shen Huang, and Celine Tricar with The Key. So there's a lot of my own personal favorite immersive stories that are deploying this type of dream logic. And I think just generally it's a way that our dreams and the way that we experience this kind of immersive, spatial, symbolic realm is very similar to the different types of experiences that we have within VR. And when you think about VR as a mode of communication, then it's a process of trying to decode the meaning of those dreams to really understand and unpack what this means. It's kind of like sometimes when you have a dream, it's not really completely accessible to you to really unpack and understand what that dream means. Well, Carl Jung and a lot of his work around dreams has been highly influential on me and my own experiences of seeing this more enchanted view of the dream life and being able to unpack the different symbols of those dreams. And there is a whole workshop that one of my listeners attended this workshop that was being put on by Martha Crawford, who is a is a former clinical social worker and psychotherapist who has been holding these dream circles and dream workshops and holding a space for these communities to come together and create this communal dream practice. And there was a member of that community named Elizabeth Hohner who started to use virtual reality to recreate different scenes from her dreams that then became this whole other level of like active imagination, like revisiting the dreams and working out the deeper meanings and sharing it with the community through this, projected 2d cinematic frame where, you know, she might be doing this workshop, jumping into VR, sharing her screen and people getting this more kind of 2d cinematic depiction of this 3d space that she had created. And so it's just the idea that you could use something like tilt brush or open brush to start to analyze your dreams, but create this communal context for unpacking the different symbols and meanings and what it means for you. And Elizabeth Hohner teamed up with Martha Crawford on Saturday, May 31st, 2025, to hold a workshop called DreamWork and Active Imagination as Creative Dialogue. I'm just going to read through the description of their workshop that they're held, since we're going to be covering a lot of similar ground within the context of this conversation. DreamWork and Active Imagination as Creative Dialogue. What does it mean to contemplate our dreams? How can art, illustration, and virtual reality become a practice for creative imagination? What does it mean to make art for the primary purpose of self-reflection, self-awareness, and personal growth? How can visual art practices help us center into a healthy, grounded dialogue with our dreams and engage with what Jung calls the voice of the nature within us? Visual artists Elizabeth Hohner and Martha Crawford invite you to join us in a conversation about art, contemplative and immersive dream, and artwork. So that was the conversation that I watched. And then I wanted to have a conversation with both Elizabeth and Martha to dig into this whole intersection of dreams, dream work as an artistic and personal reflective practice, the ways that they're working with those dreams, and also just how dreams in general is a part of the emerging grammar of how we're telling stories and sharing meaning within the context of immersive storytelling within virtual reality. So we'll be covering all that and more in today's episode of Voices VR Podcast. So this interview with Elizabeth and Martha happened on Friday, July 11th, 2025. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:04:14.277] Elizabeth Honer: My name is Elizabeth Hohner and my relationships to dreams and dream work is visually exploring the dreams through drawing and now more recently through VR 3D recreation of setting.

[00:04:28.803] Martha Crawford: And I'm Martha Crawford. I was a clinical social worker and a psychotherapist for about 30 years. The past seven years or so, I've been focused on community work and I lead several dream circles and dream workshops to help people learn how to listen kind of agnostically and thoughtfully and respectfully to their dreams.

[00:04:52.542] Kent Bye: And maybe each of you could give a bit more context as to your background and your journey into the space of working with dreams.

[00:04:58.875] Elizabeth Honer: Sure. OK, so my context of my background is I've just been paying attention to my dreams for a very long time, used to just basically journal my dreams. And then I found that I got much more information if I depicted them visually and it was more relational. I found that if I was actually able to show other people a picture of what I was dreaming, they would be in the dream with me. as opposed to me just reporting what I saw or what I experienced and having a much more over there sort of analysis. And of course, using VR technology means you can really be in my dreams with me now because you can have a real 3D presence to it. So, and I've just, I mean, aside from just being personally meaningful to me, it's, really opened me up to just sources of information and inspiration that I feel very strongly about that are available to all of us when we go to sleep at night. And I would really like to encourage other people to explore similar such material because I think it's beneficial.

[00:06:03.311] Martha Crawford: My dream work and my relationship to dreams probably started when I was a child. My grandmother was an old Quaker, and it was a common practice for her when we woke up in the morning for her to say, what did you dream last night? So being able to talk around the dinner table in an old farmhouse about what our dreams were, taught me very early that this was a kind of collective practice. My psychotherapeutic training did not, in fact, touch on dream work much at all until 2001. I started taking a course in Jungian depth psychology and dream work as a kind of postgraduate study for myself. Our first study, session occurred and we were asked to keep dream journals, not only of our own, but of our clients' dreams and any other dreams we heard. The second week of class did not occur because it was September 11th. And then we came back after that and looked at all of our dream journals. of all the dreams we'd collected. And it was really uncanny to me to see how many people had had anticipatory experiences. There were dreams of kamikaze airplanes flying down the streets of New York City. There were dreams about the tower card and a tarot deck. And there were many, many dreams that everyone in the class reported that had just anticipated this event in, you know, obscured ways, but ways that were also clear that it was readying people in some kind of way. And so I thought at that point, like, I really have to take this much more seriously. And I, you know, hunkered down and paid deep attention after that.

[00:07:33.709] Kent Bye: And Elizabeth, since you are working with the VR technologies, I'm wondering if you could flesh out a little bit of your journey into virtual reality, discovering something like Tilt Brush. And, you know, what was your pathway into discovering and finding and using VR?

[00:07:46.232] Elizabeth Honer: Sure. Yeah. Tilt brush is my primary app. I also use gravity sketch, but as far as like free expression of drawing tilt brushes and open brush now is where I go to. I've just always been interested in that kind of immersive technology. I've always wanted to be in the space as opposed to observing the space. And when I first saw tilt brush, I just thought, well, I have to have a headset. because I have to do this in my house. I must, it's wonderful. So I did eventually get the old Rift, which is to this day, my favorite headset. It's a great headset. And I started experimenting with some of the ways of creating imagery in Tilt Brush and I was just, so taken with being able to be in a space where you feel like it has real presence because it's 3D in front of you. And after that, I got involved with a group called VR Art Live. And that was an artistic group of people who were in VR and used Tilt Brush and did weekly prompt suggestions where you would get an idea of this is the week's subject and draw something that has to do with that. And so developed a lot of artistic skills in VR with Tilt Brush that way. And very quickly started seeing this is great. The imaginative part of it is immediately available in a 3D sense. when you're able to just paint with all of the directions, not just the flat directions. And after I did that, it occurred to me that dreams are so ephemeral. So if there's a way to bring that content into a 3D space, I would think that would be very interesting. So I started recreating dreams through Tilt Brush and immediately started seeing, wow, there's some information that you can get doing this that is more than if you were to, say, draw it on a 2D plane, like a 2D picture. It's great to show a visual of what it is like, whereas if you're in 3D space, it's pretty great to give a representation of what it was like to be there. So that's the best I can think of how to describe it.

[00:09:56.693] Kent Bye: Okay. Yeah. And there's a member in the VR community named Claren who purchased the workshop that you did with Martha and passed along and had a chance to watch that a couple of times. And so Elizabeth, I'm wondering if you can kind of recount your entry into this type of dream work that you were doing with Martha and how you two met and how this workshop came about.

[00:10:16.647] Elizabeth Honer: Sure, absolutely. I've known Martha for like a decade, probably a little more, I think. I actually read some of her work online that had to do with therapy because I was involved in my own therapy and I was very grateful for that process, but also really white knuckling my way through it because it was a psychological reorganization I was not expecting. So I was kind of adrift in the wind a little bit. And so finding her writing was really grounding for me. It was saying this happens sometimes, this happens to people, it's okay, this is what you might experience, these are some of the more collective ideas that happen around these sorts of things, and that might be informing what you're experiencing. It was really helpful in that way. And I had actually sort of thought of a film idea. And this was more of the 2D animation space that I was in at the time that I wanted to explore. And I was curious if she would be interested in looking at my idea and helping me sort of flesh it out and figure out, does this make psychological sense from a theory standpoint? What do you think? And met her that way. And, you know, ever since I've been following her writings and doing workshops on dreams, and I'm part of one of her dream circles. So more recently, we had been talking about, well, what's it like to visually depict dreams? Because usually when you're, I mean, from what I've experienced doing dream work, it's you write it down and you bring it to a group and we sort of discuss the content and amplify what it means to different people. And you can get a lot of rich information from doing it that way. And I very much enjoy working that way. But I also... get so much out of saying, this is what it looked like. Here's a picture of it. This is the thing. And again, if I can invite people into a VR space saying, this is what it feels like to stand in this space. So Martha and I were just talking and thought, why don't we talk about this alternative way of exploring dream material? And so that's where the workshop basically came from. And Pretty much just took a tour of a couple of the 2d stuff, but the main feature was actually me putting on the headset and then guiding people through the 3d recreation I had made of a dream space. And it's an interesting space to be in because when you're doing that, I mean, we're on zoom. So we're all seeing two dimensional depictions of each other right now. And that's the same as if you're showing somebody, even if it is a 3d recreation. You can have this sort of cinematic feel to it because you can, you know, turn angles and such and things like that. But it's still, I mean, for the viewer, a 2D thing, which is valuable, is really valuable. It really is a whole thing altogether to be standing in the space in 3D. So that is where I would like more access to being able to do that in VR. Right now, I don't really have that. I mean, open brush just released sort of a multiplayer mode where you can start from scratch, I believe a sketch, but I can't invite anybody into a sketch I've already done. So if I were to say, upload it to VR chat in a private instance, I could maybe do that. But at that point, it's a lot of technical work that I don't know if I want to devote a lot of time to, I guess is the way that I would say it. But that's sort of like where the friction point starts for me as far as being able to share this stuff. It's either I can show you cinematically in 2D or I can do a 3D thing in a space like VRChat, but it's only going to be one of them because I probably won't be doing multiple ones of these uploading them.

[00:13:51.172] Kent Bye: Right. And Martha, you shared a little bit of studying the Jungian depth psychology as kind of a postgraduate venture right around like 9-11 time period. So we're now 20 plus years from that point. And so how did your practice of working with dreams continue to develop? And at some point, it sounds like you started to do these group dream sessions. And so maybe just kind of elaborate on your journey into continuing to work with dreams since then.

[00:14:15.473] Martha Crawford: Sure. You know, so yes, I began, you know, Jung is often, and I'm not a Jungian, I argue with Jung about many things, there's many toxic things embedded in Jung's theories, but I do think his structures around dream work are useful, especially for folks in the global north, embedded in capitalism and all sorts of compartmentalization. There's a lot of ways that looking at his schemas and systems around understanding dreams were really useful. So, you know, first I applied this stuff to primarily to my trauma practice. I was a trauma therapist and and then I began branching out. And this is when I met Elizabeth. I began supporting artists experiencing creative blocks and using dreams to try to help people understand where they were blocked creatively. You know, poets and musicians and composers and authors would come to a place where they couldn't push their project forward any longer. And I'd say, well, Have you had any dreams? Artists are very good at dreaming and they're usually, you know, have a lot of language to describe what they've experienced in their dreams. And it often pointed me very clearly to places where people were blocked. I mean, I remember one artist had a dream of actual Lego blocks that they could not put in order, right? So, you know, negotiating these kinds of creative blocks is, I think, something that's particularly helpful to utilize dream work in service of. So, you know, as I began to leave trauma practice and as I began to leave individual practice, it's sort of, you know, the poly crisis began to escalate. It became really clear to me that we weren't going to be able to do all this work one by one by one by one, that I had to start to look at modalities that created small groups and helped communities begin to develop and spread out and try to get useful tools into people's hands. So, you know, in this way, I started to sort of build a dream workshop and Elizabeth showed up again and brought in some of her animations. And it became really clear very quickly that one of the important things in dream work is really understanding where you're located, right? Are you in a public bathroom or are you in your own bedroom? Are you in a living room? Are you in a train station? If you are in a private space or a public space, this can often give us information about whether you're dealing with a problem that's a extremely personal one behind your own closed doors, in your own personal basement, or whether you're dealing with a collective problem in a city street and everyone's running from the monster. So, you know, the ways that writing and visualization and sculpture and dance and all the art therapies actually can be extremely useful in kind of amplifying a dream space.

[00:16:54.929] Kent Bye: Yeah. And I think the thing about dreams that's interesting is Jung's approach puts forth a bit of an enchanted view in terms of the meaning and how these dreams are connected to the deeper parts of our soul and our soul's growth and evolution. But yet there's also a disenchanted view where people might see dreams as, oh, this is just a random firing. It doesn't mean anything. And so just curious to hear a little bit more of kind of personal experiences that each of you have had. with working with your dreams in this way, in a way that affirms to you more of this enchanted view that there is this deeper meaning that's there that has helped you to discover different parts of yourself.

[00:17:31.243] Martha Crawford: I mean, I think of dream work as a kind of internal dialogue between our unconscious, spontaneous, digestive mind that's responding to and integrating information and data and pre-conscious awareness and deep pattern recognition and creating and burping up images that just because our cognition doesn't make sense and doesn't know what it means initially, doesn't mean that it's inherently nonsense. Our emotional functions are not rational functions either, but they're still meaningful and important to tend to. So for me, I don't think that dreams are inherently... I don't want people to give over into their dream life or be possessed by it or to just follow its guidance like it's magic, because it's not. But I do think that we're healthier when we have an ongoing dialogue between our cognition and our daytime awareness and our unconscious sense of like what the developmental challenges are in front of us and what the collective pressures are around us. So, you know, we need to understand who we are as individual bees with our own tasks and our own assignments in life. But we also need to understand something about like the stressors that the entire hive is negotiating. And I think our dream lives, when you sit and pay attention, you know, it's very easy to wake up and go like, oh, that's nothing. That's gibberish. I don't understand that. Ideally, I think we want this to be an ongoing dialogue between two parts of ourselves that that may not ever agree on anything, but can disagree and interact and debate and consider each other's stances thoughtfully and productively. I think my frustration often with the hyper rationalist, like dismissive function around this is why would we still be dreaming if it was worthless? If it was actually worthless to our survival, like, you know, we clearly need our pinky toes for some reason, or they'd be completely gone by now. Right. If there is no inherent function in our dream lives that is productive for us and steers us or is useful for us or compensates, which is Jung's notion that sometimes we're inflated and a dream can be deflating. Sometimes we're deflated and a dream can be inflating. The point is these processes are trying to pull us towards balance. Not that there's like magical information in a dream that tells you how you should play the lotto. Right. Right.

[00:19:56.291] Kent Bye: Elizabeth, do you have any thoughts?

[00:19:57.612] Elizabeth Honer: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the key word for me is balance, because if you're talking about even like the hyper rational, I don't even find it so rational. I find it dismissive if you're looking at it from that perspective where it's like, well, it can only be this thing I ate or it can only be because of something that doesn't have anything to do with the deeper meaning. And then, of course, there's the full buy in from just like This means this, and I'm sure of it. And it's being able to hold it in a balance for me has been like really important. And I mean, dream work is a discipline like anything else. If you want to get better at it, I have noticed as I have been working with my dreams, they have become more coherent and more understandable. And also I realize that. That there is probably a lot of stuff I will never understand. And I am maybe not meant to understand about it because I mean, I even think of like my individual self is like being a layered thing where I have just like my individual consciousness, you know, I guess it would be ego consciousness, knowing who I am and where my position is in the world and my function. And then there's a space where it's a little less sure. And yeah, You know, it's just like, wait, am I angry on my own behalf or am I getting angry at somebody else's behalf? And that feels like that little line. And then you get into dream stuff and it's just like, okay, is this like, this is kind of like what Martha was talking about. Is this a collective consciousness situation that is appearing in my dream right now? Or is this really just personal to me? So it's just like even defining, you know, what am I supposed to remember from my dreams? What am I supposed to take from them? It's like really being, you know, cautious about not erring on one side or the other for me has been very helpful. And I don't know if anyone else experiences it this way, but whatever creates the dreams, which feels like a combination of me and also something that isn't quite me, definitely feels like it knows me better than I know myself. It will send me things that I know I'm the only one that's going to think that's funny and I got it. So that's great. But also there's some things that I can think of dream material that I've had years ago that it still fascinates me. And I don't think I'm ever going to understand. And I don't know that my conscious mind is necessarily meant to, and it doesn't mean that it won't have an effect on me. Like, I think it asks for a different kind of a conversation than just straight up. What does this mean? How do I use it? I mean, those are great questions, but they're not the only questions and they're not the only places where answers may come up. And sometimes it doesn't need to be an answer. And so just being able to sit with the uncertainty of all that is where I have actually found the most meaning. And I've been able to say, oh, wow, I really do have a sense now that this material is speaking about. something over here that's very helpful for me personally, but also this material was helping prepare me for a thing that I didn't see coming down the road, but it was actually coming down the road, or also I should just be aware of this, or I have no idea. So, I mean, there's a kind of a nebulous answer, but dream work can be so.

[00:23:03.226] Martha Crawford: And we have like shared experiences. I mean, one of the things I learned, I don't know if you're aware of this, but I've done a couple of kind of mad projects where one was where I collected 3000 dreams about Donald Trump and sorted them by category and theme. And, you know, that wasn't a hard job, right? I mean, it was hard to collect and wade through and read them certainly. The themes were very clear, right? Very obvious. We're all contending with what this means to us, not just collectively and politically, but symbolically, right? I have a similar collection where I collect climate dreams. And the fact is, when you start to look at like a large collection where the, you know, Charlotte Barak collected about 300 dreams about during the rise of the Third Reich. And when you start to look at how all of our dreams are changing, right? And all the patterns that are emerging. And, you know, I found dreams in both collections that were practically verbatim, word for word, the exact same dream, because we're contending with some of the exact same stressors. Right. Right. And so I think that's important information, too, that we also dismiss, right? We're all producing these kind of spontaneous short films or virtual reality experiences in our head at night as we're sleeping, right? Where we're immersed in a 3D environment and negotiating obstacles. And actually, and we imagine we're all completely isolated and that we're all completely alone. And actually, a lot of us are working on the exact same challenges and the same stressors and the same content.

[00:24:31.816] Kent Bye: Hmm. Yeah. And so I've certainly on more of the enchanted side, personally, myself, I have my own experiences with dreams. I've participated in a men's retreat by Michael Mead that was in the woods of Mendocino. And so he's got a dream cabin that happens at this mentoring retreat. We wake up as a group and we would take more of like people's dreams that just happened. So the immediacy of the dreams. So there's this experience I've had of this collective sense-making of the dream where You start with sharing your own meaning, and then you kind of have different layers of allowing the person to kind of discover the meaning themselves. And if they get stuck, then turning to more of these universal archetypes or asking questions. And so there seems to be this process that I've experienced in that context where. And when I'm in a community context where dreams are arising, then not only benefit from having other people bear witness to those dreams, but also to help to unlock those dreams. Because if you're just looking at it yourself, then it can be difficult. But sometimes the dreams are speaking to the collective dynamics of the group sessions that are happening there. And so it's giving information to Michael Mead and the other facilitators for other stuff that's coming up for. Yeah. how they're going to continue to guide this retreat that they're having. So I've had my own experiences of that, but I'd love to hear any reflections on this collective sense-making aspect of dreams that we don't necessarily have the existing culture to do that right now, but in some cultures they do have that. And it sounds like with these dream groups, you're able to really tap into that.

[00:25:59.676] Martha Crawford: Yeah, I mean, listen, first of all, it's the industrialized global north that has come to a place where post-enlightenment that has dismissed all of this, right? Indigenous communities around the world still practice regular ongoing relationships with their dreams. industrialized nations in Asia still are like, this is a conception dream. And this dream is going to tell me the gender of my infant and with a lot of accuracy, actually. And so, you know, for thousands and thousands of years, there existed ways for people to share dreams with their communities and with their elders in their communities. There's a rock still in Athens in front of the ancient Senate that people would come and report dreams about threats or fears or portents or boons that they thought might be heading towards Athens and the whole Senate would sit and contemplate them and digest and figure that out. I work a lot with women in different rural communities in Africa through an NGO that I consult with. And sometimes when I've talked to them about their dreams, they'll say, oh, no, no, no, this is a dream for my grandmothers. Or this is a dream that is for the village, it's not mine. And I think the atrophy of these kinds of functions is a big loss. I think it alienates us from our own intuitive function. I think it alienates us from lots of the ways that we are related to each other. And I think it's encouraging to see the ways that other people are wrestling with some of the same content that we are, that we're not so isolated in this. There are symbols that we share. And some of them are kind of global, like, I don't know, the breast. All mammals are born looking for a breast. And somehow we have a primordial image of a breast that we come on to earth seeking. It's there, it's instinctive, it's in the way we are organized. And others are very culturally specific. and become a cultural alphabet, like a symbolic alphabet. And we need to sort of be able to sit with that and understand that our bodies and our psyches are passing this information forward usefully and for purposes. And it can be extremely helpful to sort of understand the ways that some of the stressors that we're carrying are not just our personal problems. During the pandemic, for example, lots of people would be talking to me about how they were failing at something. I'd be like, you're in a pandemic. You're locked down. You're on a Zoom screen with children and animals screaming all around you. You're not failing. We're in a collective problem. But that's very hard for us to understand in a hyper-individualized culture.

[00:28:32.702] Kent Bye: What's been some of your experiences of exploring dreams in the context of a group, Elizabeth?

[00:28:38.763] Elizabeth Honer: Wow. Well, I mean, well, if you're talking about like just in Dream Group, kind of like that was a lovely experience that you shared about being in Michael Mead's program. That's great. Favorite of mine. I really love his podcast. It's wonderful. But I mean, very similar. It's very similar in that there is a sense of I'm not isolated in this. I'm not alone in this. And even if it is a very specific me problem, at least I can sit with it with other people and they can experience even as raw emotion that comes out of a dream, like, you know, grief or rage and anger or things. And people can relate to it on a pretty primal level, which is lovely. I will say as far as like group and collective things. experiencing of dreams visually is again, it's just so lovely to draw something and then have people say, I recognize this, or this is what I think of when I see this and I go, you're right. That is what that is. And then to have this recognition that perhaps these things came from the same place, even though I had a dream about it. And this person is just looking at something that I drew of it. So it's neat to see kind of like the nascent space it comes from, and then how it sort of develops in waking space. And, you know, again, it's just like, I think that visually recreating these places creates creates a more seamless experience between waking life and being in dreaming life. You know, if you can stand in a space that was recreated in a three-dimensional VR setting and you can experience sort of the same instincts or emotions that came over you in that space, I think that's really valuable. Like that's happened to me several times when I'm creating dream material in VR is I'll suddenly think, well, Oh, I was afraid over here. I forgot, but now I'm feeling that again. And that is really valuable. And then the collective way, when you've got people who maybe are looking at it or experiencing it in the same, when you're showing it to them, like to hear, have people say, what's going on over here? What's this space? You know, everyone's pointing at the same thing and it just makes you just kind of think, oh yeah, I should pay attention to that. Or, you know, it's just kaleidoscopic. It's being able to like see something from a different perspective than say my own perspective locks me into. So it's just, it's valuable in that way.

[00:31:01.754] Kent Bye: Yeah. I wanted to pick up on something that you said, Martha, because it's something that actually I've been talking about a lot when I look at immersive storytelling within the context of VR. And that's just this idea that part of the grammar of VR is turning out to be this poetic dream logic, right? Meaning that you feel like you're walking into a magical realism. And it feels like some immersive storytelling experiences are like you're walking into someone's dream. And sometimes those symbols that are being used are operating on like these three different levels. Like either it's universal archetypes and symbols where it's very clear about what the story is and what's being told. And then there's sometimes like culturally specific symbols that are being used that I'm not familiar with. And I have to sit down with the creator and have them explain, okay, this is what this meant. This is what this meant. Yeah. Other times it's very personal symbols where people would still need to have like their dream interpreted. And sometimes I can watch an immersive story and the story still comes through without having every single symbol decoded. But I noticed that Jung caution around this idea of dream interpretation of like a canonical interpretation of what the dream is versus what is coming from within. Yeah. It feels like there's this tension here between using dream logic as a mode of telling stories where you're trying to achieve that kind of universal archetype, but sometimes it's cultural and sometimes it's personal. But what I'm noticing is that as a viewer and audience, collectively, we're going to have to up our game and being able to interpret and read those symbols to be able to understand what's being said. But sometimes we're always going to need to have the dream interpreted, or it's just a part of the art where it's up to the own person's personal interpretation. So I'd love to hear some of your thoughts on that.

[00:32:42.285] Martha Crawford: Sure. I mean, there's a few. One is when we watch a film or we read a piece of poetry, right, we don't have the expectation that we need to decode every single symbol in that piece of artwork. Right. Some we see and recognize or identify with or it has some resonance and it kind of lights up. Right. You know, I haven't seen Sinners because I'm scared of scary movies, but I've heard the dialogue around it. And clearly it's a symbolically incredibly rich landscape. And people are like this moment and that moment. And when this happened, when this and people identify with it and see what's happening in that and understand are resonating with the archetypes in that landscape. Gaston Bachelard talks about, a French philosopher, phenomenologist, talks about like the poetic image, right? Which is very similar to the archetypal image. It's an image, it's a symbol that many people will find some resonance in. Poets reach into that space and summon it, right? Filmmakers, good filmmakers reach into that space and summon it, and it has resonance for us. I'm less interested in interpreting dreams, which I feel like is a kind of reductive process. A former Jungian who became a liberation psychologist named Mary Watkins, she was a student of James Hillman. She talks about especially Americans dreaming, for example, of a golden snake and then feeling like they have to chop the snake into pieces to understand all the different parts of it. And that that destroys something as opposed to sort of sitting with this golden snake and looking at it, what's numinous to you about it and what's meaningful to you about it and what's frightening or what's awe inspiring or what's aversive to you or revolting to you about it. Right. To really sit with what resonates about it instead of necessarily reduce it. But, yes, I agree with you that we have a kind of. There's been a significant atrophy in our ability to think about and respond to symbolic content generally. So, yes, being able to sort of think in it. And again, for me, this is always a deeply agnostic process where I want to be receptive to what opens up and what a piece of art or spontaneously produced piece of art that I've dreamt of in the night or a piece of art that's been created in a virtual space by someone like Elizabeth, that there's going to be a world I'm going to move through and parts of it are going to open for me and parts of it aren't. And sometimes when we go back, and I don't know if you've experienced this, but I have, there's been poetry that I've read in my 20s that meant nothing to me. And then when I read it when I was 35, and then I read it again when I was 45, it meant something profoundly different in my life. Or it opened up a completely different set of associations at a different point because I was a different person. So, you know, symbols also have their purview, right? They're not for all of us all the time at every minute. And the last thing I would say about this is one of the things that I think is important is to kind of have a boundary to exploration. One of the practices we use, I think it began with Jeremy Taylor, but many, many other dream workers use it, which is this practice called If This Were My Dream. So we're never telling ever, ever, ever interpreting to a dreamer what their dream means to them. That's always, always up to the dreamer, right? But if we sit with it and take on the dream and move through it, or think like, if this was a poem I wrote, what would it mean to me? What would I be trying to express? You can allow a dream to open information up. And suddenly a dream that's shared that is specifically Elizabeth's dream, when she shares it, all of a sudden, I can sit with that symbol and go like, oh, I've experienced that too. Not only do I see that in your dream and your life, Elizabeth, because I've known you a long time, I can see the places I've had to hack my way through a jungle, or I've had to face a giant standing on the sides of a riverbank. And suddenly, like fairy tales and scripture and poetry, suddenly we're in a space where we have to contend with our own relationship to this content. And I think that's one of the things that's really valuable about these practices as well, and being able to inhabit these spaces together.

[00:36:49.421] Kent Bye: Beautiful. Any other thoughts on that topic, Elizabeth?

[00:36:53.633] Elizabeth Honer: Uh, no, Martha said it. Great. Okay. I mean, you can, you're kind of seeing why I've been hanging out in her dream groups for years and years. Right. Because I mean, it's just, there's, it's so much richness. It's absolutely wonderful. And I mean, I wouldn't have the kind of relationship that I have with my dreams without the guidance that I've received from being in Martha's dream groups. And I feel like that was a big guiding into like doing things visually was just being like, Oh, the discussion about the symbolism. is just like, oh, this can be just for me, but it can also be for everyone else, but not in quite the same way, but it is in the same way. And I don't understand the distinction. That's really cool. So I want to keep doing that and finding out more about that. Yeah, it's really great.

[00:37:34.397] Kent Bye: Yeah, well, I'd love to dig into a little bit more about how the practice of drawing your dreams out in VR with OpenBrush, how that's changed your relationship to your dreams. And during the workshop, I know Clarence was asking you if it feels like you're re-dreaming it or re-entering the dream. And there's also Jung's concept of active imagination, which he used quite a bit in writing The Red Book, which is invoking these imaginative states where you're it's almost like you're really meditating and not letting the thoughts go away, but you're really indulging yourself into going even deeper into the fantasy and seeing that as a contemplative practice. And so as you've been drawing out these dreams within VR, you're kind of embodying them in a way that is not only revisiting them, but also able to refine and look at them in new and different ways. So just curious to hear a little bit more elaboration on what that process has been like for you now that you've been starting to kind of record and draw and paint and kind of express your imagination and your dreams within the context of VR?

[00:38:34.830] Elizabeth Honer: Absolutely. I mean, the first thing that comes to mind is that if you're going to draw it out or if you're going to, you know, recreate it in VR, in open brush or even gravity sketch pieces, it's going to take time. And so each decision that you're going to make artistically and visually demands that I re-engage with the dream content. Was this thing here? Did it really feel like this? Should I maybe include this thing over here? Does that feel more emotionally true for me? Or is that like a physical remembrance from the dream itself? So the fact that it takes time and there is a decision-making process going on kind of opens up more of the contemplative space. Cause if you're just in, I mean, and this is, I mean, people talk about flow, which I don't know if that's a thing I've necessarily experienced, but I have experienced being in a space where you're just drawing and you're just doing it. And that in itself is a contemplative space that I have found for me, where it's just, I'm just creating the thing and the decision-making part of my brain is no longer calling the shots, at least for the moment. And it's nice to have that other space open up. So it's lovely in that way. And also, especially while recreating the dream in VR, there are moments where, I think I've mentioned this before, but there will be a sudden remembered emotion or a sudden remembered piece of something that was just like, oh, that potted plant was in that corner and I felt that way about it. And so now I got to draw that thing. And what is that all about? Which is really lovely. Martha alluded to this with the poetry and the visual aspect of art in general, but I think sometimes when we take things in verbally or linguistically or by reading them, there's an automatic understandable interest in saying, well, I agree with this. I don't agree with this. And that's automatically putting you in this more judicial place in your mind. Whereas if you just see a picture of, you're going to immediately have an emotional response, perhaps instinctive response that may be coupled with a judicial response, such as, I don't like that picture, or, ooh, that makes me feel happy. But even that is just evoking or acknowledging sort of the more emotional reaction to it, which I find the visuals of that interesting. It's a nice way to sort of circumvent the automatic need to decide what my take is on it, you know, if that makes sense. So I just find that all really valuable. And the ping-ponging back and forth of those things is also a nice part of just... Spending time with the dream. Like, I don't know if I can emphasize that enough, but just spending time with it is just work in itself that I may not be able to point to something and say, oh, that's what that means about this. But I can then later on in the day think, oh. I was perhaps less crabby with this person who bothers me or things of that nature. You know, you just notice that you're having a different response and like maybe a little dream imagery will pop up. And it's just like, I don't know how that relates to this particular waking life situation, but because I spent time working on that dream, I'm grateful for it because somehow it's showing up now, if that makes sense.

[00:41:55.182] Kent Bye: Yeah. And Martha, I know that you had some great thoughts on the process of active imagination and its relationship to dreams. I wonder if you can maybe elaborate on how you start to understand the relationship between something like active imagination and dreaming.

[00:42:08.559] Martha Crawford: Sure. You know, I mean, first of all, active imagination is a lovely way to be able to amplify and play with the multiple, multivalent potential meanings that live within a symbol. Right. So, you know, to refer back to Jung, one of the things he says in the seminar to children's dreams is if you're being chased by a bear in a dream, you should stop and tip your hat and ask him what he wants of you. Right. And very rarely, unless we're lucid dreaming, which I'm not an expert at, I kind of like not having control over my dreams. I have too much responsibility for too many things in my waking life. So I kind of like to let my dreams unfold. So when I'm being chased by a bear in a dream and I'm terrified and I'm running in the morning, it's really nice to be able to sit in a contemplative space and sit with that bear and kind of go like, wow. What is it you want from me, dude? Why are you chasing me? What is the pursuit for? What are you hungry for? What do you need? Why are you here instead of where you belong? What energy are you summoning? And to be able to sit in a playful way and in an imaginative way, a creative way, and interact with that symbol so that I can have more spontaneous imaginal data about what kind of conflict I'm contending with. I also just think that, you know, not everybody is geared toward contemplative practices that are, you know, what maybe Catholicism and mysticism would call like the via negativa. Not everybody can sit in emptiness, right? Not everybody can sit in silence. And in fact, it's contraindicated for people with severe trauma. Right. So sometimes it's easier to have a focus and sometimes that symbol or that image or that tone or that event. You know, I just finished an essay that Elizabeth kindly illustrated that was very helpful, where I was suddenly plopped into a scenario where I had to play a French horn and I've never played a French horn before. So I got to sit in this scenario and really think like, what does the French horn mean to me? And why am I, why am I sitting here with this French horn in my lap? And, you know, the practice of drawing it or writing it can be in itself a kind of active imaginal exercise. But, you know, I think it's a very productive contemplative frame. Some people want chant or some people need a centering word to focus on. Some people need a mantra. And I think imagery can be a very grounding way for a lot of people to engage in contemplative practices. You know, once they understand the form and the practices around it and how to stay grounded, I think it can be really important. I mean, the same way that we see that psychedelic therapies can offer people a lot of important data at important crossroads, that's important symbolic content that's rising up. And we know that that can be useful for people at end of life or for people experiencing severe trauma in certain circumstances when there's a proper frame around the experience. We're sinking into that space most of the time, right? Even people who think that don't have any dreams, they're having dreams. And usually I find when they just pay a little bit of attention, their dreams start to pay them forward, right? Like to go like, oh, you're listening now. Okay, I'll cough up some more, right? And I think being able to sit with this contemplation of like, why did my psyche, why did my body create this suitcase of rain that every time I open it fills the room with water, right? Like, let me sit with that image and think about what that might mean.

[00:45:42.244] Elizabeth Honer: concrete example of active imagination using recreation and VR for your dream material. And just as an aside, I would love a suitcase full of rain. I think that'd be very useful, honestly. But I recreated a dream of mine where I had, let me see, there was like a lower level and an upper level and on the top of the upper level in the right hand side there was this woman who was screaming with her hands on the side of her face obviously in distress and she was surrounded by these other people who just kind of stood looking at her did not know what to do with her and on the left side there was frankenstein's monster and he was dropping ice cream sandwiches down to the lower level which is just i mean you just report that and it's like this is, yeah, this is dream material. We're in dream space right now, obviously, but recreating it. Like I was able to actually, once I had recreated it, I suddenly became aware of a sensation where I did not want to go in that upper right room where that woman was screaming. I didn't want anything to do with it, but what I had the opportunity to do was actually like in a tilt brush or open brush for the way, just select her. Right. And then take her out of that room and and then put her seated on a couch that was in the lower area and I could just sit next to her. And that was a form of contemplation where I took that actual dream material out of the scenario that was making her that distressed. And I was able to just put her there and just be with her. And again, I can't give you like a clinical, well, this is what happened. But I just know that after that, I felt better about her and I felt better about whatever the situation was. And it was really just a relational thing where my waking self was just relating to my dream material that was obviously in distress. And after that, I put her back into that space because I know that's where you were in the dream. So that's, it is her, you know, my, her problem to contend with. Right. But at least I feel like I've been with her now and sat with her. And that was comforting in a way that I don't know that I could have gotten to it another way. So that's for me, a pretty good example of using an active imagination scenario with the VR experience. recreation artwork in that way.

[00:47:54.869] Kent Bye: Yeah, it's a beautiful example and anecdote. And Elizabeth, just a quick follow on in terms of working with VR and your dreams. Just curious if you've had any experiences with lucid dreaming, if it's been deepened by working with VR, or if there's just a deepening of your relationships with your dreams in general by doing this practice of drawing in VR. Just curious if you could maybe elaborate on that.

[00:48:16.943] Elizabeth Honer: You know, it's interesting because I mean, I've occasionally will run into a lucid dream, but the problem with me in lucid dreams is that when I realize that that's what's going on, I get so excited that I wake myself up. So I'm never able to actually stay in the dream, which is really honestly very annoying. It's just like, Oh my God, it's a dream. And then it's just, All of a sudden I'm in my bed again. So that's a little frustrating. But I will say the thing that is really funny, and this probably just happens to everyone depending on what their discipline is. But I've started to see VR mechanisms show up in dreams. So I'll find myself teleport. recording across spaces with that little blue circle showing up and jumping me across spaces, which is imagery that's available to me now because of VR. I've also run through portals a la VRChat and found myself in a different world in my dream. But for me, that is now visual language to examine the collective and personal psychological content. in that way. It always just feels like that is the overarching container. I think that's, I mean, again, that's what I love so much about DreamWork is I feel like we're bombarded by things like, you know, just social media stuff and what other people think all the time and other people's agendas, advertisements. Now we've got like AI generated material, which, you know, that's its own conversation for sure. But again, it's all coming from outside. But then when you go to sleep at night, the dream space is using all of that material to talk to me directly. You know, it's just like if I'm talking to an AI chatbot in my dream, that's still my dream communicating with me through an AI chatbot. What do AI chatbots mean to me? And in a similar situation, this is like, what do these VR mechanisms mean to me? What does it mean to sculpt something in 3D space that I can manipulate a lot of gravity sketch controls? What's going on psychologically? So I move in that direction with it.

[00:50:12.418] Kent Bye: Nice. So one of the things that this more enchanted view of looking at dreams has led me to think around other types of philosophical paradigms, like Alfred North Whitehead's process philosophy is a big influence. And he has an idea of eternal objects, which are kind of non-spatial temporal objects. objects that are before they get into space time. And it is very much in alignment to what Jung would talk around in terms of the archetypes. So I've used a lot of archetypal thinking in my practice of the elements as applied to presence and just generally thinking around these archetypal principles and symbols. I wanted to read this quote from Jung and get your thoughts on the nature of archetypes. And this quote has to do a lot with the irreducibility of archetypes, but also how they're kind of in an ongoing process that is incomplete and continually being fed back to evolve and grow. But I just wanted to read this quote. He says, clear-cut distinctions and strict formulations are quite impossible in this field, seeing that a kind of fluid interpenetration belongs to the very nature of all archetypes. They can only be roughly circumscribed at best. Their living meaning comes out more from their presentation as a whole than from a single formulation. Every attempt to focus them more sharply is immediately punished by the intangible core of meaning losing its luminosity. No archetype can be reduced to a simple formula. It is a vessel which we can never empty and never fill. It has a potential existence only. And when it takes shape and matter, it is no longer what it was. It persists throughout the ages and requires interpreting ever anew. The archetypes are the imperishable elements of the unconscious, but they change their shape continually. Yes. Yeah. Love to hear some thoughts on that.

[00:51:52.540] Martha Crawford: I mean, I think to me, this is really the tension that we're experiencing culturally with people really wanting to dismiss these nonlinear ways of processing, right? We want objects to be fixed in time. We want to reify our thoughts. We want dreams and scriptures and folk tales and fairy tales and artwork to be able to read them like a car manual, but they're poetry. And we don't decide what a poem means once. Right. We decide what it means over and over and over again and really allowing. I mean, listen, in some ways, I think it's still some very old dualities that we're stuck in. We want to know, is this a yes or a no? And the fact is, it's a 360 degree continuum and it can mean one thing and it can mean it's opposite and it can mean everything in between. The question is, what resonates for you in the moment? What lights up? What feels clarifying? What humbles you? what makes you go, oh yeah, no, that's me. Right. I was, I was just talking about a dream. I'd just written this essay with the French horn dream about how I spent so much time in this dream over explaining things. Right. And I'm like, oh yeah. Oh yeah. No, that's me. Right. Like, and so part of it, there should be an experience where the dream is giving you information that you don't know about yourself so easily. It should be giving you information about the world that you don't like and what you look like from behind, right? That you may not really want to know about, right? Like, so when we allow the dream to have multiple symbols and not control it too intensely and try to decide what it means once and for all, it allows us to kind of explore even maybe like a Rorschach, like what are all the potential creatures in this vision. And even to the degree that it might be a projective, that is a useful experience. What are we projecting onto it? What have we instilled it with? And what do we imagine it means? And what would we not want this dream to mean? And what do we hope it means? And what do other people hear in it? And I think it's just a useful, deeply useful way to allow our thoughts and our beings to be fluid and responsive to our intuitive life and to the world around us. And without this kind of ability to consider things as being multi-meaningful, multivalent, I think it leaves us with less ability to respond to all sorts of challenges that we're facing in the world.

[00:54:27.654] Kent Bye: Beautiful. And as we wrap up, I always like to ask people looking to the future, and I'm usually focusing on the technology itself of VR. And Elizabeth, you can certainly add that. But I want to ask it more generally in terms of what is the ultimate potential of dreams? And if our society would have a deeper relationship to dreams and what that might be able to enable. And perhaps VR as a technology might be able to help facilitate new ways of collective dreaming. But yeah, just curious to hear each of your thoughts of the ultimate potential of deepening our relationality with dreams.

[00:54:59.318] Elizabeth Honer: I mean, I think you kind of touched on it with that amazing quote that you found. That's a fantastic quote. It's really how I have experienced the archetypal. It speaks to me deeply in just how I've understood it in my own life. I think that dreams, because they are just so generative and they're always presenting new and new. feeling like it's inscrutable information, but then eliminating information. I think that's where that space sits. And it's this idea of saying, whatever's happening right at this moment, there's more, there's more that is accessible. There's more that can be found. And it's just, there's, I guess, as an artist, whether I'm drawing traditionally or I'm working in VR, there's a bargain, right? There's an understanding that as soon as I create a drawing, I am dropping an anchor in time because I am using the visual information that is available to me right now. Even if I am working with something that is alive at all times, like those archetypes are, and they're going to be speaking in infinite ways, the only way they can speak in infinite ways is through us that drop those anchors in time by using what we have. So my hope is that just by being more connected with dreams, especially like visually or, you know, in any way, really, it doesn't have to be visually, but I prefer visually just being able to see things and recognize that and say, well, I've never seen that in my life, but I bizarrely recognize it. And what does that mean? What does that mean for me and you say, if you drew it, but what does that mean for all of us collectively? You know, what are we more deeply connected to? And I just, especially now, I think that's more important than ever is just being able to have this source of wisdom that is available to us every single night when we go to sleep and just having some awareness, way of working with it in waking space that we can be more connected to each other and find ways to process a lot of the issues that we're going through today in a way that feels more connective and collective as well.

[00:57:02.757] Martha Crawford: You know, I'm thinking about how the medical model's attachment to Freudian models of dreaming has taught most people that dreams are embarrassing and that dreams are revealing, icky, embarrassing personal information. And therefore, dreams are too intimate to share and it's boring. This is a common refrain. Like, don't tell me your dream. All that person is going to tell me a dream at a cocktail party. I can't wait to get away from them. Right. This idea that somehow dreams are only about like our scatological impulses and our sexual desires and our aggression and and other frames, indigenous frames talk about dreams as being like the voice of nature within us. I think if we are rejecting the spontaneous unfolding processes that our bodies are offering us and that nature that we're actually embedded in are offering us all the time, When we reject that and reject our relationship to that, I think it puts us in harm's way in really profound ways. And I think it's part of, I don't think it's the whole thing. I think there's many other layers that I also address in other areas of my work. But I think our reluctance to deal with uncertainty and fluidity of meaning and spontaneity in symbolic life and the inability to read what feels alive inside of us, I think this is important data about how to live healthfully among other people and in the world. And right now, everybody's devaluing that. And now it's emerging as wild acting out behavior, as insane conspiracy theories. I mean, our dream lives are now, because they've been so devalued with inside of us, they've been projected and splattered all over our collective life. And nobody's in the same reality anymore. And they're being manipulated by propagandists and advertisers and algorithms. And we're still in our dream lives all the time. But people are just pretending they're not. And I think if you do it in the right place in the right time where your body's actually calling you to do it, maybe it doesn't have to be as acted out. And maybe we don't have to be living in a world that's so filled with illusions like a hall of mirrors. Yeah.

[00:59:27.677] Kent Bye: Beautiful. And just wanted to give a quick shout out to Richard Tarnas. And he's a Jungian and philosopher who I think pointed me originally to this quote. He's done a lot of great work with his book, Cosmos and Psyche, where he dives into a lot of the more esoteric, hermetic and astrological meanings of the archetype. So yeah, I think he pointed me on to that quote. But yeah, I guess the final point is just if you have... Anything else that's left unsaid? Anything you want to point folks to, to the broader immersive community or people want to get more involved in their dreams? I know that Martha, you have some ongoing workshops and groups and essays that you're writing. And yeah, just any final thoughts and what you want to point people towards if they want to dig into more information and also for Elizabeth as well, if you want to point folks to.

[01:00:11.860] Martha Crawford: Well, I have resources that are available at my website, which is whatashrinkthings.com. And there's lots of important resources that are available, not just from the psychological traditions. I think it's really also important to listen to Indigenous practitioners and healers around what this symbolic life means. You know, Jung was attempting to try to reintegrate the indigeneity that we had split off and abandoned in ourselves in the Global North. And, you know, my grandmother, as an old Quaker farm wife, was somebody who lived still very close to that space, right? And, you know, I think we have lots of internal resources, but you can definitely find more on my website. And Elizabeth's dream art is extremely beautiful. You can see some of that at my website, but mostly at hers.

[01:00:59.042] Elizabeth Honer: Well, thank you. I mean, yeah, go check out Martha's website, whatashrinkthinks.com. That's where I have learned quite a bit of my own relationship with dreaming and like a language around it that is very helpful. But I will also say with the idea of like, you know, tracking the more indigenous cultures, as far as like their unbroken relationship with dreams, like ours is broken, right? And so we have to find a way back to it. But I think that VR... Offers a really exciting way to do this. That can be like indigenous to us where we are in society right now, as far as just like us and what you're saying is the global North. In that area. I just think that being able to like do 3d explorations of things in VR in this way. I mean, everybody who jumps into a headset is just like wow, this is great. And that's, that is an immediate response. And I think that there's something to pursue in that. So, I mean, I don't necessarily have any of my own resources to point to because they all come from other places, but I just want to absolutely champion that we do have an opportunity here. I think with the VR space to actually rediscover and redevelop some of our own archetypal relationships with this stuff.

[01:02:08.254] Kent Bye: Beautiful. Well, Elizabeth and Martha, thanks so much for joining me here today on the podcast to explore the fascinating topic of dreams and using VR to deepen your relationship to dreams. And there's a lot of potential there for not only what the dreams are telling us for our own personal development, but Ways of doing collective dreams or even going into immersive storytelling and VR experiences is a way of sharing these type of universal collective dreams. So it's a part of the emerging grammar and language of VR. And I feel like watching these experiences has led me to want to talk to folks like yourself to help to deepen that level of symbolic fluency and ability to appreciate the ways that the dream life is coming into the affordances of how we're communicating and telling stories within VR. Yeah. in maybe even explicitly exploring our dreams in that context, like you're doing with your work, Elizabeth. So yeah, thanks again for joining me here on the podcast. And it was a real pleasure to learn more about each of your journeys into working with dreams and to learn a lot more around the nature of dreams and helping us connect more deeply to ourselves.

[01:03:09.491] Elizabeth Honer: Thank you for having me. Yeah, it was a delight. Thank you so much.

[01:03:12.776] Kent Bye: Thanks again for listening to this episode of the Voices of VR podcast. And if you enjoy the podcast, then please do spread the word, tell your friends, and consider becoming a member of the Patreon. This is a supported podcast, and so I do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring you this coverage. So you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Thanks for listening.