I spoke with ReVerse Butcher & Kylie Supski about The Continuous Present as a part of my Raindance Immersive 2025 coverage. See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

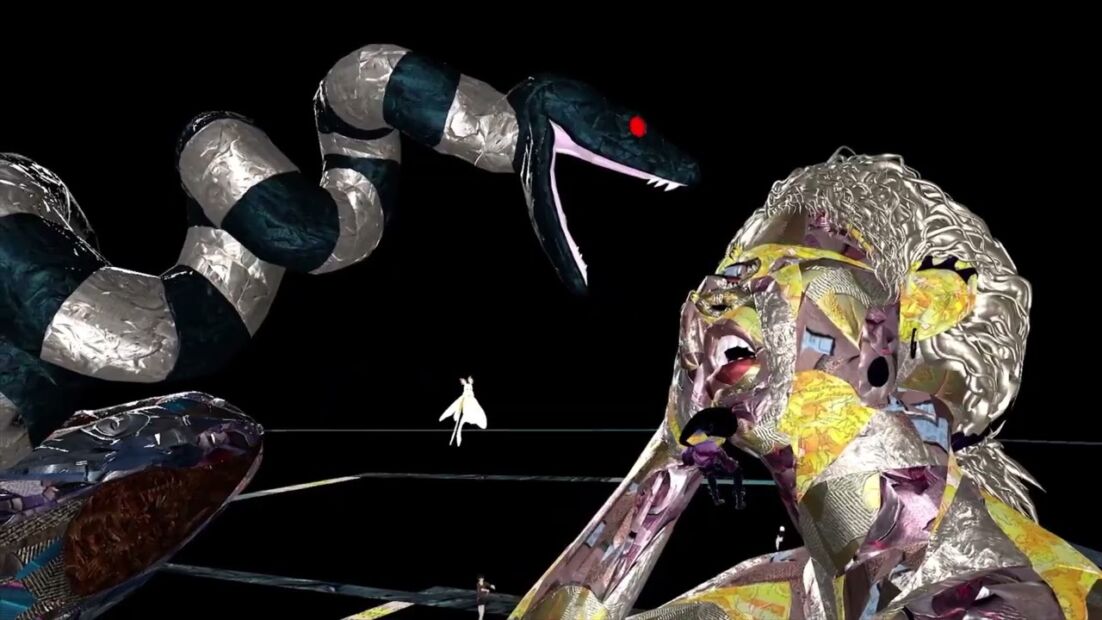

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling in the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So continuing on my coverage of Rain Dance Immersive 2025, today's episode is with the winner of the best art experience called The Continuous Present. It's a collaboration between Rivers Bircher, who is creating the world and all the different immersive art, as well as her wife, Kylie Supski. And so they collaborated on the poems that are being featured here. And so you end up walking into this kind of loading room. You go into this long hallway where there's a series of different poems that you're reading. And then you go into this other space that when you're in that space, you see this big immersive sculpture that's probably like 10 or 15 stories high, usually of these different bodies that are in different configurations. And you're able to jump up different levels. And so there's like invisible floors that you are able to walk all around the different immersive art and then, you know, get to the top and then kind of go on to the next chapter. So there's like four or five different chapters. And the last chapter is with a live poetry reading from Kylie Supsky. So the poems are very logical in its form, making these different kind of repetitive arguments around trying to understand the different nature of love and connection and the nature of time even. And so lots of big themes that it starts with the poetry and then from the poetry building out all these other different dimensions. the other aspect is that reverse butcher as an artist is creating lots of different collaging techniques and so very much like kind of a blending of physical technique within the context of vr and so creating these composite collage textures from text and then using that within the context of these huge large sculptures that are being painted within the context of tilt brush but also the music is created within the context of vr and so when you go in and are looking at these different sculptures then you're also listening to a reading of the poems that you just read but also listening to the music that's there. And so it's kind of a multi-sensory experience. And then at the end, you have this kind of opportunity to kind of like talk about different experiences that you've had within the context of the art that you've just seen. Also worth mentioning that in the next interview with the piece that's called What is Virtual Art? The artwork of Rose Bridgers also featured in the fourth section of that piece as well. so check out the next interview to check out that piece and that piece the what is virtual art is available on vr chat so you can go check that out but the continuous present is not available for anyone to go check out just yet although it might be here in the future that's yet to be seen so we're covering all that and more on today's episode of the wisdom vr podcast so this interview with reverse and kylie happened on saturday june 12th 2025 as part of my broader rainy and submersive 2025 coverage so with that let's go ahead and dive right in

[00:02:56.098] ReVerse Butcher: My name is Reverse Butcher, and I'm a VR artist. I work with VR sculpture. I work with music composed natively in VR using Virtuoso VR, and I make artworks and experiences that work towards poetry, fine art, and music.

[00:03:12.283] Kent Bye: Great. And maybe you could give a bit more context as to your background and your journey into this space.

[00:03:17.741] ReVerse Butcher: Right. My background actually comes from fine arts and from performance, not from VR or computers. So actually, yeah, VR was something that I discovered about five years ago and then upskilled. So, yeah, I didn't come from a sort of a programming or a gaming background at all. But it's something I absolutely love and it's absolutely transformed my creative practice. I just finished making a book called On the Rod, and it was an artist's book, so it's a one-off. Everything was hand-painted and collaged and whatnot, and I took a found copy of Jack Kerouac's On the Rod, and I over-painted and over-collaged every single page to make it a feminist wonderland, because the book irritated me and it was sort of a way of talking back to culture. When I finished that book, I was at a bit of a loose end. And that book had sort of transformed my main focus from performance and publishing to something that was sort of more visual. And I'd always had that in my practice, but it was almost like I decided to step off the stage and do something different. And then when I finished that book, A friend of mine locally, who was also into poetry, had seen that book and said, I've got to show you virtual reality. And he was working for a local Australian VR company at the time. And he brought over a computer and a headset and said, I'm just going to leave this with you for three days. Put me in tilt brush and then left. came back three days later I made this poem you could walk through and he was like I'm gonna leave this with you for another week and then he you know went away for a week came back to pick it up and I built all this other stuff and he's all like I'm gonna leave it with you for a month and then after that I was like how do I get one of these things you know, tell me what I need to buy and what I need to learn. And he pointed me at what products were available and how to get started. And then I was on my way. But yeah, the idea of bringing something from like a narrative structure, this idea of poetry that is experiential was always something very core to my practice. But I had done a lot of that on stage. And it happened sort of around 2019 as well, which was just before the pandemic hit. So it was almost like the timing was perfect for me to do something that was actually sort of more solo based. I used to do a lot of like traveling and like you'd have to get on a plane to go anywhere to, you know, reach an audience outside of the Australian context, which is a lot of investment, time, money, you know, all of that stuff. It's a huge involved process. Whereas with VR, I could already look to the international context from my home studio. So that was very exciting for me.

[00:05:50.009] Kent Bye: Were there any other VR pieces of art or experiences that really inspired you as you started to develop your practice of creating spatial poems?

[00:06:00.273] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah, absolutely. In terms of spatial poems, I didn't initially find other people making those, although I have now. I did find people making works with music. So that was my sort of entry. And that's another part of my practice. So I ran into Rue. at the wave XR very quickly. And there was a group that we were all involved with called VR Art Live. And I was a volunteer on that discord for a while, I think until 2021. And we did some large scale sort of like festival, VR festival events, you type things with art and music. So that was my main entrance. I did sneak poetry into even the very first delivery in the wave though, but it was a sculpture of a skull and it had these, crying rainbows coming out and going out and there were flowers all over the thing and it had handwritten poems in every single color going down all over the thing so it was really sort of an interesting experience to watch people who were like into gaming and and maybe not into poetry come up to it and go whoa what is the words i want to read the words and i was like great okay this is a thing we can do here so that was probably early inspirations yeah

[00:07:13.991] Kent Bye: Nice. So it sounds like that you were involved with some of the music scene in terms of, you know, the way of XR, the way VR turned into the way of XR, but also creating music within VR. Can you speak to a little bit around, you know, whether or not you were doing music before that, or if you really came in to start to generate music because of your access to the tools within VR?

[00:07:37.188] ReVerse Butcher: No, I mean, music has always been a part of my practice. When I first started in my teens, I learned the euphonium and the drums and classical and all that stuff. But I found it very stifling and I didn't really stick with that for very long. I did very well at it, but I went directly to experimental music after that. So I sort of I wanted to sort of see what music could do if it wasn't sort of stuck to these very rigid principles. boundaries. So yeah, I've played in goth bands and punk bands and psychedelic rock bands and a lot of experimental music and stuff like that, often with a spoken word element as well, using things like chaos pads and loopers and all those kinds of noise generating things. But it wasn't until, again, I sort of took a I hit a creative wall with my live performance practice. It wasn't giving me the same kind of joy. And I didn't feel like I was able to reach the people with the ideas I was trying to get across in a really constructive way. Performing live, you know, as a woman on stage, your body is on the line all the time. There's a lot of, you know, it's a physically based thing. Yeah, you have to be very present and it's not always necessarily super positive. And after a couple of decades, almost two decades of that, I was over it. I just wanted to make art and I wanted to not necessarily be the person that they were looking at while they were experiencing the art. So, yeah, I wanted to get out of music and performance, and I found Virtuoso VR. It's an app that's made by a very small independent team who are brilliant, and it basically is a whole bunch of spatial 3D synthesizer instruments. Some of them are like a drum kit, which you could play in real life, and some are not playable in real life because they only really can exist in the terms of VR, but... What's brilliant about it is that you have the studio in your headset. Nobody else is listening to you around. The police can't be called if you're making too much noise. Nobody's going to hassle you. Your neighbors aren't going to complain. And you can mod it a little bit and put in your own helm patches. So it becomes this really versatile tool to be able to create very in-depth content. experimental music. So you can play a note, reach in and bend it while you're, it's the best. I just, I adore it. So it really reinvigorated my love for composing music and it allowed me to do everything I needed to do by myself without really requiring too much from other people. Yeah.

[00:10:03.802] Kent Bye: Very cool. And I'm just going to welcome you, Kylie, into the conversation.

[00:10:08.564] Kylie Supski: Hello, how are you?

[00:10:11.186] Kent Bye: Doing really well. Thank you and welcome. I wonder if you'd be willing to go ahead and introduce yourself and tell me a bit about what you do in the realm of immersive art, immersive performance.

[00:10:20.319] Kylie Supski: Hello, I'm Kaili Sobski. So we are currently living in Ballarat. And so before COVID, I was very active in a Melbourne spoken word theme and theater. We did the play together. I was doing photography at that time as well. There's beautiful botanic gardens in Melbourne. And then COVID happened. So it's all stopped. And we ended up in this beautiful old hotel. And with a really interesting project, we were both asked to write the opera, text to the opera. And Reverse was designing the visual for it. So that took us like two years. locked in in this really old spooky building and then after three years of COVID we were looking at different places where to go so we at the end we decided on Ballarat which is like close to Melbourne it wasn't our like first choice because we were thinking about actually going to Europe and Portugal and then we were thinking about Canberra in Australia and Tasmania which is really beautiful like New Zealand And yeah, we ended up in Ballarat, which is an amazing town. It's a small town, but it's so welcoming. There is a big artist community and they are really encouraging artists to get involved. And we got amazing opportunities. So I've got currently the... photography exhibition on this laneway in the center of the city. And in August, I'm going to be involved with Foto Biennale, which is like an international photography exhibition in Ballarat. So that's very exciting.

[00:12:09.755] Kent Bye: Very cool. And I think one of the interesting things about VR is that it's a place where people from all sorts of different backgrounds and training and expertise are able to come in and push the edge of their own artwork through the medium of VR that allows them to be inspired in different ways. And so I always like to get a little bit more context for folks' backgrounds. So I'd love to, if you'd be willing to share a little bit more around your background and your journey into the space of this intersection between art and technology and performance.

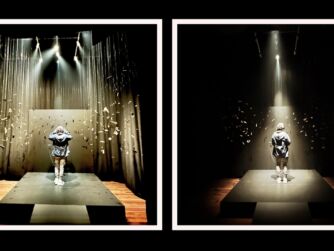

[00:12:38.820] Kylie Supski: Well, I'm originally from Poland and I finished the Master of the Green Logic. And then when I came and migrated to Australia, I got involved in IT. It was sort of a way of maintaining and getting money to maintain whatever you want to do. And I got into the poetry when I moved to Melbourne from Perth. And I was always working with technology. So when Reverse Butcher started to be interested in VR and building virtual sculptures in virtual reality, that was amazing. At the beginning, I was doubtful because she didn't have a technology background, but she picked up and in five years she achieved so much. And then because of COVID and limitation of performing live, I got invited by reverse to perform poetry in virtual reality. At the beginning, I was very sort of resisting about it because performing in VR, it's so different. It's sort of like performing on a Zoom call. We had some poetry performances on Zoom calls during COVID. And it's sort of like you're facing the screen and there is no... I've loved the connection with the audience when you're on the stage. I did a lot of performances on the street in Melbourne. and some political performances. And so performing electronically, like on a Zoom call, that was sort of like limiting because you don't have this connection. In virtual reality, that was different because you're sort of in this space that everyone's got avatars. I think there's more possibility of connecting with the audience in virtual reality. And my first big performance during the Rain Dance Festival We were rehearsing and rehearsing and then having 50 people, 50 avatars, you know, sending emoji and everything. It's amazing. So, yeah, that was my journey to virtual reality. I don't really do much stuff in virtual reality, but certainly performing poetry and spoken word in virtual reality, I think I'm going to do that again. So, yeah, that's very exciting.

[00:15:06.343] Kent Bye: Nice. So it's interesting to hear about that background in logic because I can see traces of that logic in terms of having a bit of an argument or like exploring more paraconsistent logic or logic of paradox or, you know, like in girdles, it was either consistent or complete. Most people choose the completeness, but there's a certain amount of inconsistency or things that are incomplete or that feels like there's a bit of like exploring that paradox that, you know, looking into more of the quantum metaphors to explore topics of love. And just curious to hear a little bit more around your creative collaboration and your project, because, you know, you have a series of poems that you're starting with. And the fourth poem is really focusing on how everything starts with the word. And so it sounds like you're starting with the poetry and then from the poem, then expanding out into the world and creating the spoken word performance of that. But I'd love to hear a little bit more around your process of starting with the poem and where this project began and how you start to work together as a team to put these series of poems together.

[00:16:10.936] Kylie Supski: So yeah, the process is sort of like the inspiration where it comes from. I usually draw a lot of inspiration from interacting with people, reading a lot of other poets, and philosophy, and the science. And that really affects my process, how I'm writing, that I get all these ideas and inspiration, but then when I look words, I look words and how they work together as almost like in mathematical equations. How do they connect to each other? It's sort of like someone said to me that My poetry is very sort of structured and logical, and I like the clean list, so I could have an inspiration. And then this process of editing, that's where my background in mathematical logic, and I've initially actually started the theoretical physics. So I did one year of theoretical physics, seeing life and EMC square being proven, in like five lectures and I had amazing lecture which actually was one of the people on earth that understands theory of relativity and then it came back quantum physics and then I've concentrated on mathematics and especially logic so the way how I'm connecting that idea is very I'm exploring this sort of a you mentioned Godot theorem which is very fascinating but I'm finding as well in Recently, I was writing things for this photo biennale exhibition. When you look at nature, how nature builds things, it's completely different to how humans approach The architecture, for example, I'm writing about the architecture of nature. So the photography that I did was as well as observing nature and flowers, how it's all built, that affected my writing as well. So yeah, the process is that I will get the ideas from texts, philosophy, poetry, and interaction with people, which is a really big part of it. And then I will be sort of thinking about it for a long time, and moving words around and very often playing on a computer, playing back using computer voices, how it sounds. I remember what Gertrude Stein, which I really love because she was very, you know, she came from science background. how she approached language as basically like a structure. And she once said that you have to hear how you're feeling when the words are coming out of your mouth. So what is the feeling that you experience? It doesn't really matter what they mean. I'm not paying attention much to meaning, like someone is asking what this poem means. I'm more about the feeling and what you're feeling when the words are coming out of your mouth. This whole concept of, so after all this inspiration, I'm playing with words, listening and editing and working together with reverse butcher on the poems that were screened during the Rain Dance Festival. That's interacting with another person and exchanging ideas. That's even more rewarding and enriches what you're actually creating. Because you've got two different, you know, mind workings together. And it's very sometimes full of friction. And it was funny, a reverse was mentioning to other people that writing the laugh, a poem about laugh, that was the biggest frictions that we had together.

[00:19:56.374] ReVerse Butcher: I think it was 25 drafts.

[00:19:59.937] Kylie Supski: So that's my process, getting the inspiration from environment, from interaction with people, from interaction with poetry, with science, quantum physics. I'm listening a lot to quantum physics and then working it and seeing how is that going to work when you actually reading or performing i really believe in a spoken poetry how it sounds and like you can read the poem and you get completely different impression that when you actually hear yourself even how these words are coming out of your mouth and how you experience that and so that's my process

[00:20:42.409] ReVerse Butcher: I find performing live when you're doing that, it's a bit of a, it's quite an intimate gift to give to your audience, regardless of whether they're sitting in the same room with you or whether they're in a virtual space, which is as embodied as you can get in the virtual world for right now. Yeah. You're able to sort of like when, when something's read, you don't necessarily get tone. The context is different when you're reading it to somebody or performing it to somebody. It's a very different feeling. I hope on both sides.

[00:21:09.363] Kent Bye: Yeah, the structure of this immersive experience of the continuous present is that you have a big long hallway after you go through a disclaimer window, and you're reading the poem to yourself first, and then you're going in and seeing a big giant sculpture that you've put together that has a lot of collage textures, but you're then also listening to a spoken word performance of usually the same poem and sometimes it's like exact word for word and sometimes there's like slight deviations, but more or less there's the music that we talked around that you were generating over top live performance. And so I found it like kind of an interesting multimodal experience where you get like repetitions of the poem where you're listening to it while you're watching and paying something to something else after you've already read it for yourself. And the poetry itself has a lot of repetition. So just to kind of repeat through different ways that you're consuming the poetry. And so, Rivers Berger, I'd love to hear, it sounds like you're also co-writing a lot of these poems.

[00:22:08.546] ReVerse Butcher: We did co-write poems. Yeah.

[00:22:12.048] Kent Bye: And so, you know, as you're starting to think around, like, this overall journey of the continuous present, Was there an idea of like, these are the themes that you want to explore from like love and time and other things? Or did it start with some existing sculptures that you'd created in VR? Like just trying to get a sense of where did you begin and how did you start to map out like what would be the most interesting topics to cover over the course of four or five poems?

[00:22:39.619] ReVerse Butcher: Well, we started with the poems. The poems were the base. So that was what we did. And we had this feeling that we wanted to make a work that was sort of about the idea of wonder, of being outside of yourself. A lot of other kinds of works in that theme are ecclesiastical in nature. They're sort of, you know, you get this sort of religious idea, but neither of us are religious. We don't really believe in that. But we do believe in this idea of something greater than yourself and an experience greater than yourself. And giving somebody something on that scale is possible in VR. So we started with the poems. And then after that, I thought about the symbols and how I would sort of create the same kind of feeling or the same message within one frozen frame. So, you know, that's with a sculpture. You don't have animation. It's not react. like an animated thing. And a lot of digital artworks and artists lean towards the idea of animation, whereas I lean away intentionally. I like the challenge of trying to do everything in one symbolic frame with a lot of fine detail into it. I borrowed from sort of alchemical symbology a lot of the time. So there was, you know, the rebus, the creature with the masculine and feminine sort of in the same body. And that was something that the alchemists, in alchemical books, when... You know, science was witchcraft and you could be topped for that. They often spoke in symbols and that was one for perfect balance. And that really appealed to me. So it was this idea of opposition with things being different, but still being equally weighted and both equally necessary. And the idea that, you know, we contain multitudes. Everybody is, there's a spectrum of this kind of thing and it's okay to be anywhere on that spectrum. So yeah, that's just an example. And then the music came last. Should we speak to how it initially came together? Or I think we probably should just mention it.

[00:24:33.935] Kylie Supski: I was going to mention about the continuous present. Yes, do you want to, please? Go ahead. The whole idea of continuous present It's Gertrude Stein again and T.S. Eliot and the quantum physics. The idea of the time as such is T.S. Eliot in fourth quote talks about it all the time. The past, the present, the future all together joined and looping. and creating this continuous presence that the past, present, and future, it's building to this continuous presence where we live. And it's not really that we live in a past or a present or a future. It's this continuous present. James Joyce, I got actually a tattoo of James Joyce about the continuous present. Hold on to the now, the here, where the present plunges to the past. So that's the idea of continuous present, where it came from. And I'm fascinated with this idea of time. There is this living in a now, but I think we're living in a continuous present. It's a stream of time and that time is not like linear. It's just everywhere and nowhere. So that's about the continuous present where we're talking about it. Do you want to talk about it? How... This whole idea started, you've mentioned something.

[00:26:04.249] ReVerse Butcher: Oh, no, I want to speak to what you're speaking to. The idea of time being not linear is something that appeals to me and my experiences as well. So definitely in terms of, you know, when you're experiencing something that, you know, makes you overwhelmed or, you know, with wonder, that's the kind of thing we were hoping to go for. You know, time does become sort of elastic. And again, in the VR space, this idea of time being elastic is sort of, It gets very odd. You're both embodied and disembodied. And I think your embodiment in terms of having a body is how we feature or how we function within time. If we didn't have a body, we wouldn't probably experience time in the same way, I think. But yeah, that's probably getting a bit woo-woo. Anyway.

[00:26:48.857] Kylie Supski: And in virtual reality, you're sort of a, you're not really in a space as we see it, three-dimensional space.

[00:26:57.141] ReVerse Butcher: But we are.

[00:26:57.741] Kylie Supski: That we, like in America or we in London or in Australia, we are in virtual reality in this continuous space that is not located anywhere. You go to VR and you talk with people that are sitting in houses all around the world. And I think that that connects with time, that time happens. There's different time zones on Earth. But when you're in virtual reality, you are in this continuous presence. You're talking with people. I'm not sure what time is in your place now. It's around 11 here in Australia, but you're probably in a completely different time. So this whole idea of time and space gets blurred in virtual reality. And that's amazing.

[00:27:43.346] ReVerse Butcher: And there's so many things you can do in that liminal, space that you can't do in physical installations or physical performances you can't do it and as an artist that's you know the cutting edge for me that's that is so compelling for a space like well okay well if the boundaries were this and now the boundaries are this how what's the next step you know so um that's how yeah

[00:28:09.275] Kent Bye: Yeah, I wanted to say a few things around time because it's something that I think about quite a lot in terms of, you know, the Greeks had two words for time. There's the chronos time, which is the measurement of time, the more linearity, you know, how you're scheduling and starting a specific moments in time. And then there's the kairos, which is the quality of the moment of the time, which is more of like, what's the feeling or the qualitative aspect or what's emerging right now? When's the auspicious time or the right time or the right moment? to do the thing. And to me, the Kairos really leans into that cyclical nature of time where there are kind of a sequence of a story of our lives. It's unfolding where we'll have memories or moments that are connecting us to the past and through our memories. And, but also we'll be looking into the future as well. And so, you know, this idea that it's all happening all at the same time and that our experience is linear in the sense that it's unfolding like is an unfolding process with an era of time, but that it's, so much of the feeling of our lives are connected to these moments that are in this more cyclical or more like polychronic rather than monochronic and kind of more that cyclical nature. So it seemed like intellectually a theme that's being explored quite a lot. And I feel like the use of paradox or oppositions and polarities where you're saying love is this, but also the opposite and having this sense of in terms of gender, like a binary of gender, but also breaking out of those binaries into more of a spectrum. And so just curious to hear from each of you some of the experiences you've had in your life of this either cyclical nature of time or, you know, trying to break out of binary spectrums through paradox or... contrasting polarities, which is a theme that I see throughout. I'm just curious to hear some ways that that's connected to your life experiences that you wanted to bring that out and explore it in this art.

[00:30:02.289] ReVerse Butcher: That's a great question. Do you want to start or?

[00:30:05.290] Kylie Supski: Continuing with time, and I'll get back to the binary. You know, time is like money. And we notice time because we've got watches, we counting and imagine people who are living in a time before the time was invented, and they were just, the time was only counted by the night and day, and before people had money. So because we've got currency, we are constrained by financial worrying about it, and the same with time, because we've got clocks on our phones, on our hands, and we constantly pay attention to it. So time and money, and in this poem there, to stop time, laugh is to stop time, That's what it is when you laugh, when you're in love, all these things going away and you live in this continuous present. But going back to your question, the binary, you know, how we think I came from the country that's really, really strictly Catholic. So everything is, you know, and when I left Poland, it was still communist or socialist Poland and everything was black and white and white. to be queer that's something that you don't really talk about it and everything was in red and white because you could see this red everywhere and white so there was this like gray background everywhere and the only thing that you could see is red and white and this binary condition of Poland being very catholic I was brought up in a very Catholic family. I had religious classes until I was in high school. And this, you know, how Catholicism thinks in a binary criteria. And then when you liberate yourself from that by migrating and that's completely open completely different perspective how you look on things when you meet people that that are queer and how you can change the way how you're looking at yourself how you can change yourself and from that comes this really amazing inspiration and enrichment that you're not trapped in this idea of right and wrong and men and women. And I've got this piece that I've performed in Melbourne, Binary Thinking, how we think politically about how our country should be, about migrants and, you know, this binary trap. I think it was called Binary Trap. And by exploring all of this and liberating myself from I don't mind, I'm not speaking about religion, but the liberation from my upbringing was really, really liberating, and how I approached then creativity and looking at things, and get the confirmation from it, that when you look at science and nature and philosophy, we're not supposed to be binary. So that's where my sort of inspiration, do you want to?

[00:33:28.532] ReVerse Butcher: Sure. I mean, those binary things you're speaking to, I think, are social constructs, really. And, you know, trying to break through and find a third or a fourth or a fifth or a space outside of those two expectations has been something certainly that I have been, you know, that has been a big factor in my own life, you know, in different ways. But Yeah, in respect to time, like I suppose my experiences with this idea that time is not linear, like I didn't have an upbringing that was religious at all. I did have a fairly conservative upbringing, but not a religious one. But yeah, it came from sort of like, you know, creative experiences, you know, performing psychedelics, those kinds of things. But, you know, that idea that there's a transformative nature to and that not everything will remain the same all the time, and that maybe all time is happening all the time, and maybe the story that is happening is always happening, and that there isn't like a break, or there's a lot of different ways of looking at it. Kylie has had a very sort of classical education around the idea of quantum physics and whatnot, whereas I've had a little bit of an unorthodox one. So that sort of really complements the way we can write stories about this together she will come at it from a very analytical point of view and I will come at it from a but how does that feel kind of point of view so we're really able to sort of speak to that and that's why we have so many arguments about certain poems because I mean with the two-stop time poem and specifically How can you possibly say anything brand new about love? It's like trying to describe the moon. Everybody has done it. How can you talk about it in a way that is both intimate to your experience and, you know, universal to everybody else's? So that was such an undertaking. We thought, oh, write a love poem. Sure, let's do that. That'll be fun. Ha ha ha. It took a really long time and it was actually really beautiful because I think that along with time and this idea of counting or measuring things, another measure of the human experience is words. The way that we define something forces it to be one thing and not another thing or one thing and not other things at the same time just by the nature of the way language works. which is incredibly limiting because several things can be true at the same time. And also what's true can change over time. So, you know, it's as a poet who loves words and who loves language, trying to escape it while using it You can't, but you do, and you try, and you have to almost deconstruct language, which is where all those collage techniques and those experimental poetry techniques you see me using have informed my practice, because the very structure, the skeleton of language, letters, all of those things, when you start bending and cutting and placing and replacing and assembling them in different ways, you see how meaning is multiple. And being able to represent that is very powerful if people can go on that journey with you and they can see it. And I always encourage other people to try it because the minute they try altering a book or cutting up a poem or any of those things, they suddenly see, oh, wait, everything is not as fixed as we think it is. And that's where shit gets really interesting for me.

[00:36:39.967] Kylie Supski: Yeah, language is really tricky and the limitation of Wittgenstein talking about language and we suspend it in language. It's actually, language is very binary because you've got words and they've got certain meanings and when you see these words you immediately associate the meaning. So to liberate the words and talking, for example, about laughing language, I've got this line, you can't describe laughing words because words are blind. They've got this binary attached. Even if one word means a lot of things, it's still very binary. It's still one, two, three. And it was very interesting quote from what Niels Bohr said, the quantum physicist. And that they're trying to explain the quantum physics, which no one still understands, and there's no good explanation for it, the same like consciousness. And he said, and I love this thing, that he said, language... in quantum physics has to be used like in poetry. In poetry, how you use language, you don't create the meaning by using words in poetry. It's more about creating images. So you combine words to create images and feelings and experience. The same like when you paint something, you don't use red and green and blue. You mix the cards. So when you mix the words, although they separate, but when you speak them, when you read them, they create images. And that's what he said about to understand quantum physics, you have to approach that like almost like poetry point of view.

[00:38:25.069] Kent Bye: I think that's beautiful.

[00:38:27.310] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah.

[00:38:28.482] Kent Bye: Nice. For the first picture, I wanted to ask around the use of symbols and this juxtaposition between, you know, using language, which I think is more of like an air element abstraction language where you're communicating these deep thoughts and concepts and ideas, and then you're moving into more of a spatial context. So drawing more upon like architecture and sculpture and kind of more of the spatial context, but also it feels like, you know, having like a still life of a moment, like a shot, but like in 3D. So it's like a sculpture in 3D with all these other collaging techniques. But it feels like I'm walking into a dream, walking into your dream. And I'm hearing some poetry, which is kind of like the meaning of interpretation. But these scenes feel like there's also like they have a lot of symbolic pregnancy in terms of. even deeper meaning above and beyond the words. And so just curious if you want to comment on your process of creating these sculptures and the kind of dream logic of letting the symbols speak through trying to draw upon these more universal symbols from alchemy and other other ways of just spatial relationships between people and the emotions on the faces. So there's a lot that you can communicate with the spatial context, with the art and the sculpture, and just curious to hear a little bit more around your process and how you start to think around the use of this type of symbolic dream logic in your art.

[00:39:52.677] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah, well, I mean, I think the minute you start to cut up language, you know, symbology and meaning becomes multiple and it becomes weird. You know, things start to happen, you make new connections. And that's definitely informed the way I've started to think about spatial and virtual sculptures. In terms of like the dream logic, I think that the subconscious and the threads that sort of drive us as human beings that we might not be totally in control of or not be totally aware of are kind of really important. I've got mine. You've got yours. She's got hers. And we may not understand them ever, but they do sort of thread through most of the things we make. In terms of like the emotion and the sculptures and the way they're sort of put together, I thought very much people sort of accept ideas or they connect to ideas in different ways. So having the text available to read, having it audibly available. sort of read aloud, having the music there, having the sculpture, all of the things are talking about the same idea. And that sort of gives people as many opportunities to connect to it in their own way as we can manage, which also gives us the pleasure as artists, as being able to experience all those things and link all those things together and control as much of that narrative as possible. But saying that the minute you create something and let it loose to the world, it ceases to be yours anymore. And people will make their own interpretations. If you look at No Beginning, the sculpture for the part four, with the four characters sitting and the faces going off into the eye, into the sky, it is about this idea of how many people are we in different contexts. We contain multitudes. We may say one thing and feel another, or we may feel one way and that may change. And what was really interesting to me was as I was watching people interact with the different faces on the masks is how different people interpreted different emotions off every face. There were people who saw, you know, happiness and, you know, maybe a conniving nature, the same thing. Some people saw fear and sadness. Some people saw, you know, sort of like rage or fear, you know, and it was just really interesting for me as the artist because I didn't expect that. That people were going to obviously take something very different away from what I intended. And that's OK. I'm really happy about that because you share the narrative and it becomes this shared experience. And in VR, you can do that because there is that sense of digital or virtual embodiment that people can sort of at least experience the virtual space in a somewhat embodied way. But it's this paradox. It's both embodied and disembodied. And that's what I try to do with the sculptures, too. This idea of what does it feel like to have a body and what does that mean? What kind of body and how can it speak in a particular way? Also having the idea of the body as environment or as landscape was really important to me. This idea of being able to travel through it in detail as an artist, that was important to my process. And making sure that there was a wide variety of different kind of bodies represented as well was a big thing for me as a feminist. So there's a lot of, it's a complicated question. I hope that's given you some answer and not too much rambling. Was there something in particular you'd like me to focus on or?

[00:43:02.995] Kent Bye: Oh, no, I guess the Ouroboros with the two women is particularly rich in terms of like the Ouroboros has a lot of meaning from like alchemy and the snake eating his tail, but there's a little bit of a remix to the way that you framed it rather than just a singular entity eating its own tail, you have two. And so it's sort of like a little bit of a shift of how the metaphor usually is. And so I'm just curious to hear like what that meant for you.

[00:43:31.388] ReVerse Butcher: Sure. Well, I mean, the Ouroboros certainly was probably the most difficult one to sort of, I guess, digest. Like it was quite challenging for a lot of people. It was challenging for me to make as an artist. There's the idea of the yin and yang, the balance again. You've got the idea of like the visceral nature of birth, I think, as well, which is often erased from a lot of classical art, you know, or even any kind of narrative around birth. There's this idea that You know, a woman goes into labor, screams, baby, that's the end. Oh, no, that's not how it goes. And this idea of sort of being connected by pain, I think, and being connected by this shared, very secretive, very sort of private or intimate experience that women have every day, all the time, all over the place doing this. But, you know, I also sort of, yeah, this idea of rebirth was important as well, the snake eating its tail. But, yeah, I did remix it. That is very true. Yeah, I can I can sort of speak, I guess, a little bit to like as a person who is not capable of having a child. Like that was also sort of me thinking a little bit about that kind of thing. It's not been something I've been sort of like desperate to do my whole life, but there is certainly a certain pressure and pressure. uh societal narrative around women who don't have children or who maybe have stepchildren which is my experience so um and they're no less your family you know but maybe you haven't had the experience that a parent that has given birth has had it's very different so yeah that's that's some of it yeah

[00:45:02.386] Kent Bye: Yeah, thanks for that. I think, you know, part of the language of VR is using these archetypal symbols. And so I find that sometimes they're universal symbols, symbols that are very specific to cultural context, and then sometimes very personal symbols. And I feel like this project is kind of spanning the full spectrum of different levels of symbols. And so I appreciate the additional unpacking of that. Yeah. So the collaging, I'd love to hear you maybe elaborate a little bit on the collage, because the collage is something that seems very specific in terms of the texture that you're adding, the different colors, the kind of remixing of text. And so just curious to hear a little bit more elaboration on the way that you're doing the texturing of these sculptures. Sure.

[00:45:43.693] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah, well, the textures are very unique to my practice, and they sort of stem from my earlier traditional art stuff that was sort of visual poetry, which is this kind of work that really sort of stands over the border of image and text-based artwork. It looks more at the idea of what the function of text is, not what it says, but what text does or what it can do. So it leans into some of those things about collage, erasure, poetry, all of those experimental things, which were, you know, initially very male driven, male dominated spaces, the beat poets on William Burroughs and all those people who sort of really defined those spaces at that time. Just part of the reason On the Rod happened, actually, was a way of speaking back to that culture. But yes, I had started initially building those collage pieces to sort of try and show how meaning was multiple in existing texts. to reach this idea of the third voice or the third mind, which is a William Burroughs thing, if you've ever heard of that. But yeah, painting on actual texts is quite freeing, especially if you find a text you really don't like or you think needs some work. With a pencil, a pair of scissors, and even a little marker, you can change history quite literally. It's fun. Anybody can do it, and it's very accessible. But, you know, the further you go along with those experiments, the more things become abstract and the larger the ideas and the more universal they sort of become and the more your relationship to image and symbols and meaning become nonlinear or broader, in my experience. From a technical side of things, once I created one of these Vispo works, I would then go on to photograph them with a high-quality camera, put them into Adobe Substance Sampler, which is an app that allows you to create normal maps and all of the different kinds of maps you need. And you can add things like metallics and masks and all sorts of things. I got quite down the rabbit hole with it, and it's so much fun. It allowed me to sort of create this really textured image material, it's like mixing paints almost, but sort of, you know, even more because you've got layers and layers, you can have, you know, PBR maps with 10 layers of effects on them, and I do quite often. So yeah, being able to make these kinds of things created an extra layer to the sort of visual language I was able to use in regards to the sculptures, like returning to Ouroboros, there's actually one, all of the textures on either side of the sculpture either figure in the sculpture are remixed and mirrored so they're actually the same textures but with different color remixes the main one the main one is one called three and it's because of the idea of three is the two parents and the child so um it's you've got uh one that's sort of quite yellow and and and tone they've got another one that's purple and orange in tone and they're sort of contrast but but they work together. It's a harmonic color balance. And that's kind of what I wanted to show. So, yeah.

[00:48:41.391] Kylie Supski: Nice. It's really fascinating to watch reverse, watching this process, because when you see the final product, it's a beautiful texture. And you may think, oh, it could have been created. And some people say, oh, can you create this then? They don't realize. how long and how really manual step this process is and watch this process is absolutely amazing it's like watching god designing our whole universe because you you look everything that's a lot of pressure man it all looks but it is sort of like And it's such an amazing process to watch and how complex it is and how much creativity. So when you look, when I look at the final product of reverse structures, I see soul. You know, I see it's sort of like going into the restaurant and eating some amazing meal prepared by the chef and going to the fast food and eating something. It nourishes you. The art like this nourishes you. I'm not going to mention the AI because it's such a problematic thing, but I think there's no soul in something that is created by machine and quickly. It's the same like the practice, manual practice, how things were made in the past and how they're made now. we're talking about art that has stalled. So the pressure of experience watching through this whole really long and elaborated creative process.

[00:50:23.567] ReVerse Butcher: I'm very lucky to have a supportive wife. No, no, sorry for interrupting you. I have a supportive wife who often I come in with this idea that sounds completely batshit and I cannot articulate it. Like just before, when I'm trying to, you're asking me to articulate something that almost, the point of making it is that words have failed. So there's almost no way to explain it in a clean or concise way without either talking for a long time or someone experiencing it. And I mean, I do have a book coming out through Steel Incisors, which is a small press based in the UK in September called Torn Textures and Hybrid Glyphs, which goes into Vispo and making all of that stuff. There's an essay in the beginning and it does talk a little bit about turning it into digital materials or PBR materials and putting it into virtual spaces. And this idea of spatial poetry where it doesn't remain on the page in one way, like you can fly through it or walk through it or experience it in different ways. So I'm happy to make sure you get one of those when it's released if you want. But yeah, trying to explain some of that Vispo stuff in a short timeframe is quite challenging. So thank you for bearing with me.

[00:51:29.790] Kent Bye: Yeah, for sure. You know, I think that's, you know, I do a podcast, so I am putting people in these impossible situations all the time of sharing my experience and having them talk around, you know, what they were thinking when they made it. So it's just part of the process. And it just helps me kind of understand the larger context of how things were made. Sure, sure. One of the things that I wanted to just bring up in terms of one unique thing that I think that you've been exploring in your art is the exhibition of that art in these different virtual contexts where there's a whole other experience called what is virtual art, where a lot of your art is featured in the fourth section of that. And both in that piece, as well as in the continuous present, you have this ability to go from to take your sculpture and to blow it up into like huge scale, like 10 story to 20 stories hall. And you have this mechanic of in the what is virtual art, you're kind of walking up a ramp and then overlooking and seeing different perspectives of that same art. And in the continuous present, you have a more of the ability of jumping through a ceiling, but the ceiling's invisible. And so it's like a reverse normal where you're able to land on this level of the air, but you're still able to look both up and down. And it gives the viewers the ability to really walk around your art 360 degrees. And I really appreciated how, you know, you could have made it small and I could have just seen everything really quickly, but by making it that scale, it's something that's a unique affordance of VR, but also allows me to have completely unique perspectives on the art that I wouldn't normally have a chance to have if it was an art in physical reality. Since you are doing sculpture and you can recreate sculptures in physical reality, but the exhibition of these is so unique that I'd love to hear any comments on the development of this exhibition strategies for making these huge scale pieces of virtual art and having ways for people to kind of explore in unique and novel ways using VR.

[00:53:17.065] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah, I mean, if you were to try and recreate any of the sculptures I've made for either the continuous present or what is virtual art, you'd need, you know, several million dollars in an airport hangar. You wouldn't be able to do it. And that's part of the reason why, you know, VR is such an intriguing medium to me as an artist. When I'm sculpting those things, they're at that scale. They're large. That's how I get all the fine detail. If you want the tiny moon on a fingernail or the eyelashes, it's got to be big, you know, and... One of the things somebody told me a long time ago when I was sort of starting out was that, you know, galleries, they really love big things. Don't make miniatures. And this was after I'd done 10 years of miniatures. And I was like, well, fine. So I sort of thought I don't have the time, space or funding to make anything that big. So I'm going to keep making miniatures. But VR allowed me to scan parts of the miniatures or to photograph and to rebuild or to reconstruct in a way that they did feel larger than life. And the idea of being able to walk into a book or a poem or in this case, a sculpture was incredibly compelling. And I didn't see a lot of other people at that time doing miniatures. similar kinds of things. Since then, I have met many fabulous VR artists who are doing the same kinds of things on different scales, or they're building in that regard. But you do have a lot of freedom to create these sort of dreamlike spaces that are very unreal. And yeah, I sort of don't think that if you've got the capacity to do something that breaks all the boundaries of physics, why would you make something that doesn't you know why would you do something that just involves sitting in a chair and looking at something or walking down a hallway that's i mean like we did have the hallway because you've got to ease people into it otherwise they'll just freak out but you know if you can well why wouldn't you that was just my approach i guess But I must say that Jessian from the Virtual Museum of Virtual Art, he did the design of the spatial thing, the building and the ramp sequence in the art gallery beforehand. I mean, we were talking in depth about how that might look. But, you know, he's a proper developer. I don't know what I'm doing with Unity on it. I learned what I did and I did my best. And he put up with me shouting some choice words at the screen many times for many months, trying to figure out how the hell to make that work. But Jesse was, you know, he, that's his world. He knows how to do it. So it was beautiful for me as an artist to hear and see someone like him takes such a considered approach to the art, the questions he asked me about it, the narrative and the way he built the narrative around it and this idea of the environmental narrative that he built around it was really beautiful and I will be forever grateful. He did such a beautiful job with it.

[00:55:49.431] Kent Bye: Yeah, it was really, for me, the highlight of that piece was seeing this new way of exploring this kind of large-scale art. So yeah, some real innovations. I'm looking forward to talking with him here soon. Oh, great. Awesome. Well, as we start to wrap up, I'd love to hear what each of you think is the ultimate potential of virtual reality, immersive art, and visual poetry, and what it might be able to enable.

[00:56:12.756] ReVerse Butcher: Well, I think that as the technology becomes more and more common and people are adopting it and it's easier or more affordable for people to sort of, once it becomes as ubiquitous as using a smartphone or something like that, we will see more and more people able to access these kinds of experiences. which is something I'm looking forward to. The idea of cross-platform stuff is interesting too. But VR, as it continues to develop, as the headsets get smaller and more comfortable, I feel like there's only going to be more opportunities for collaboration, more opportunities to sort of expand consciousness and to build these kinds of experiences. And I mean, as an artist, I've gone in directions that I didn't even know existed 10 years beforehand. And I'm looking forward to what in the next decade presents itself. Because I think that if we try to imagine what it is, we're creating a boundary for ourselves already. And there's already going to be new things that we can't expect. And it's our job as artists and as thinkers and as creators to be able to train ourselves to recognize those new ideas and work out how to expand and connect with them.

[00:57:15.194] Kylie Supski: I think we sort of at the stage, I remember computing in 1980, we are at the stage with virtual reality or a punch guard and the computers that occupied the whole building. And look how much progress was made from 1980 to now. You've got the computer in your phone. So virtual reality, we just sort of just slightly opened the door. But when this door is completely open, the opportunity for art is absolutely amazing.

[00:57:46.162] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah, I think so. And I'll be looking forward to seeing what those new capabilities afford us to experiment with, really.

[00:57:55.580] Kent Bye: Awesome.

[00:57:55.840] ReVerse Butcher: Anything else?

[00:57:57.542] Kylie Supski: What's that? Something to really look forward to.

[00:58:00.364] ReVerse Butcher: Yeah, yeah. Anything else?

[00:58:03.066] Kent Bye: Yeah, anything else left unsaid that you'd like to say to the broader immersive community?

[00:58:06.670] ReVerse Butcher: Thank you for coming along and engaging with it as you did. It really lifted up the artwork in a way that we couldn't do on our own, and it was an absolute pleasure and an honour to present it to you all, basically.

[00:58:19.921] Kylie Supski: And I'm really looking forward to performing on a poetry with the avatar and the chore glasses because that's really, I love doing that.

[00:58:29.971] ReVerse Butcher: We have some ideas for a new project.

[00:58:31.733] Kylie Supski: Thank you to everyone for coming to our shows.

[00:58:34.557] ReVerse Butcher: Finally, we'll be front and center, I think.

[00:58:38.353] Kent Bye: Awesome. Yeah, one other quick follow on. You have a new world in Viverse. Do you want to say a few words around that?

[00:58:44.397] ReVerse Butcher: No, I do. I do. It was a great project to work on. So HTC's creator program for Viverse commissioned me to create something called The Last Stanza, which is another art and poetry experience, but it's been gamified and it's cross-platform. So if you don't have a headset, you can still play it on your PC or mobile, which is fantastic.

[00:59:03.348] Kylie Supski: a bit exciting for the half of my um my audience that doesn't use vr because they're probably interested and they haven't been able to have a chance but now they can i think you just created a new form of poetry oh no i think there's a lot of people in a form of a game which is amazing because it opens so many doors to people there's so many people playing games she created a poem In a game.

[00:59:28.363] ReVerse Butcher: It was a lot of fun. And the prizes are poems. So you go through and you collect the stanzas. And the idea of the game is, where does the soul live? And then there's a number of different sort of plot points or levels that all engage with a sculpture. So is it the heart? Is it the brain? Is it the foot for the journey? Is it the eye for what we see and all of those things? And it just asks the player to... engage with those ideas on their own terms. And then the final prize is sort of like the final stanza. But I don't want to give it away because I hope everybody will play it. Working on Vibrous has been a dream. They've been delightful to work with. It's a very smooth and exciting and engaging platform. And I really look forward to seeing what they do with it next.

[01:00:08.348] Kent Bye: Awesome. Well, Kylie and Reverse Butcher, thanks so much for joining me today here on the podcast to break down a little bit more around your process of creating the continuous present. There's certainly no lack of deep ideas and thoughts and, you know, exploration of poetry and visual poetry and using the multimodal ways of exploring all these different similar themes in different ways. And yeah, just creating new ways of exploring this vast immersive art and Yeah, just really appreciated all the deep thought that went into each of these pieces. And yeah, just also the experience of being in VR and seeing the live performance and seeing the interplay between poetry and VR. Samantha Gorman of Tender Claws is also a poet. And so I really appreciate just the ways that poets are coming into VR. And I feel like the use of metaphor is something that poets are already using. And so this kind of visual metaphors and this development of the symbolic logic and archetypal ways of communicating, I think is a natural affordance of, you know, like walking into someone's dream. And I feel like that's going to be a language that's continuing to be developed by both the artists pushing forward what's possible with how to communicate, but also as an audience, upping our own levels of being able to read the omens and interpret the symbolic meaning of what's being communicated. Yeah, I feel like lots of really rich ways that you're exploring all these different themes. And yeah, just really appreciated hearing a little bit more about each of your process of creating the continuous presence. So thanks again for joining me here on the podcast.

[01:01:35.869] ReVerse Butcher: Thank you so much for having us. Thank you for having us. For everything, Kent. Thank you. Thank you.

[01:01:41.684] Kent Bye: Thanks again for listening to this episode of the Voices of VR podcast. And if you enjoy the podcast, then please do spread the word, tell your friends, and consider becoming a member of the Patreon. This is a supported podcast, and so I do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring you this coverage. So you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Thanks for listening.