I spoke with Michaela Ternasky-Holland at the Immersive Design Summit 2019 about her entry into the immersive space, some of her early immersive storytelling projects, and working with at the Museum of Ice Cream as a creative assistant to the founder. See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR Podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR Podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So on today's episode, I'm going to be digging back into my archives to have this vaulted, unpublished interview that I did with Michele Tarnaski-Holland back at the Immersive Design Summit back in... February 23rd of 2019. And so part of the reason why I'm digging into this is because I ran into Michaela at the Onassis Onyx Summer Showcase to talk about her latest project, The Great Debate. And I've interviewed and featured Michaela four other separate times, but there's actually two other unpublished interviews that I have with Michaela on other separate topics that I just wanted to dig into just to have more of a complete evolution of different aspects of Michaela's career into the She dipped in and out of immersive design into VR, and now she's doing much more of like artificial intelligence storytelling. So it's just kind of like a interesting career trajectory that we talk about how a lot of the funding of XR and immersive storytelling has dried up. And so now she's got her focuses on to like more AI projects. But I just wanted to go back and to air some of these unpublished interviews and conversations that I had with Michaela. So I did this conversation with Michaela at the Immersive Design Summit and at the opening night party to the Museum of Ice Cream, which has a little bit of conflicting opinions within the immersive industry because these end up being like selfie palaces, people going and taking pictures. selfies of themselves into these different spaces. And so it's kind of got this bad rap. And so we talk around that. And then I also share my own direct experience of the resistance to that lore and baggage that I'm bringing in, but also finding myself reveling in some of the spatial immersive experience of diving into a giant pool full of these kind of plastic objects. nuggets and finding myself feeling compelled to like share a photo of that moment but we also talk around Michaela's entry into this point and a little bit more of her early stage of her career of different projects that she was working on at Time Magazine but also like the piece that she showed at the Sheffield Documentary Film Festival in 2018 face-to-face also some of the other projects that she was working on before she kind of went off and did some of these independent productions and So after this conversation, the next interview that I published, which I think is actually the first public interview that I did with Michaela, was when she was working with On the Morning You Wake to the End of the World. She was an impact producer for that project. And so we talked a little bit about the plans for On the Morning You Wake to the End of the World. So that was premiering and won the top prize at South by Southwest 2022. And then at Venice Immersive 2022, there was the premiere of this trilogy of Quill animation pieces that was called the Reimagined series, where they were taking like these folklore stories and kind of reimagining them in a contemporary feminist women-centered context. And so the first one was Nisa, and that showed at Venice Immersive 2022. And then I actually did an interview when I was in France for New Images and Michaela was there after touring around on the morning wake to the end world all over the world they actually wrote up a white paper that was describing some of the lessons learned from creating these impact projects and so in the next episode we'll be diving into that unpublished interview and then after that on Tribeca immersive 2023 is when they had the second volume of reimagined and that was Mahal and I did interview with the creators of that and And then finally, I did some remote coverage of South by Southwest 2024 on the third edition called Young Thing, looking at Reimagine Volume 3. So in the process of interviewing Michaela this year at the Anastasonic Summer Showcase, there were like references to these other moments that then I went back to like dig into the conversation I had at Reimagine. new images. And I was like, oh, there's other references to even prior conversations. And so I just wanted to go back to my backlog and air this in a trilogy of unpublished interviews with Michaela recounting different aspects of her journey into this immersive space. So we're covering all that and more on today's episode of the Voices of VR podcast. So this interview with Michaela happened on Saturday, February 23rd, 2019 at the Immersive Design Summit in San Francisco, California. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:04:28.646] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Hi, my name is Michaela Holland. Currently, I am the creative assistant to the founder of the Museum of Ice Cream. But my in to the immersive design kind of field and just immersive interactive genre in general was actually VR and AR. And then before that, it was actually being a dancer and a performer at big theme parks, Disneyland, SeaWorld, Legoland, as well as Disney Cruise Line. So that's kind of my growth into this experiential world. Backwards.

[00:04:56.609] Kent Bye: Interesting. Yeah. So how did it begin for you to start to get into this immersive realm?

[00:05:01.894] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah. So I was 19 years old and I was dancing against my parents' wishes professionally in Los Angeles area while going to school full time at UC Irvine for journalism. And so moonlighting was kind of like what I was doing and happened to go to a audition and book Disney Cruise Line, which was a contract that began in two months. So I quit school and did a nine month long Disney Cruise Line contract as a 19 year old and was one of the was the youngest performer on the ship, youngest crew member on the ship, and just kind of immersed myself, quote unquote, in like a weird meta way into an immersive environment that wasn't just the client facing end, but also on the back crew operations and obviously that then like sparked my interest in like okay if I'm about to go back to school for journalism and I'm about to go back to UC Irvine and leave a life in the Bahamas and traveling around the world and living my best dancer performer life I'm going to make sure I make every moment count. So I took all the skills I learned at Disney, also taught myself video and audio skills while I was on the ship, brought that back to my school, brought that to kind of what was then a literary journalism program, very written-oriented, long-form-oriented. We were learning Seabiscuit, studying Gay Talese, studying Joan Didion, studying very much long-form. How would you write a novel about nonfiction events? So really good storytelling. But then realized, you know what? Everyone I talked to, all of my professors, it's like, print is dead. There's no money. Get out of media. And I was like, well, people spend thousands of dollars going to Disneyland. How can I bridge nonfiction storytelling in Disneyland? And that's really where I got my journey started.

[00:06:44.643] Kent Bye: So it sounds like you were doing there and had journalism and dance and interfacing with these different theatrical elements. How did virtual reality then come into play for you to get into this immersive design in the context of VR?

[00:06:57.527] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah, so it was June 2016. I had just graduated school. I was in LA working as a production assistant on commercial sets and other things and making a name for myself as a PA, trying to work my way up to being an AD, assistant director or director one day of film, thinking that That was something I could do while I was trying to figure out what immersive interactive was for nonfiction and just happened to stumble upon a panel that was a VR related journalism panel and was like, I could do that. Like I had hot flashes, I had chills all at once. I was like, that's what I'm supposed to do. And I like ran up to the panel. And I was like, how do I get involved? And they were like, well, you can start teaching yourself 360 video. And just like I did on the ship teaching myself video and audio storytelling, I then just fell into teaching myself 360 video storytelling techniques and how I would do it. Saved up some money, bought a camera. I would go to a set all day, go to Disneyland and perform at night, and then be at like 3 AM in the morning teaching myself how to stitch footage I had captured over the weekend. Then so one of the projects I started working on was a homelessness project in Orange County where I followed different groups of homelessness, homeless people in like the Chapman University areas in the like what they call like the ditches or under the overpasses of Orange County and just like finding all these amazing people who just unfortunately were homeless at the time and documenting their stories using a 360 camera. So yeah, that's kind of how I got my in on VR.

[00:08:18.516] Kent Bye: And so, uh, was that the face-to-face project or was that something else?

[00:08:21.578] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Totally something else. That was like kind of my gateway drug into VR. I then went on to be very lucky enough to get a job in New York city, working for Life VR with Mia Trams at the helm. She and I together worked on volumetric VR experiences. So we did like a historical experience called Remembering Pearl Harbor, a volumetric capture of Buzz Aldrin called Cycling Pathways to Mars. We worked on a project called Lumen with Stanford Medical Hospital about calming your mind and body through breathing in VR. And then was actually able to do a ton of 360 videos. So from the course of late 2016 through all of 2017, I covered the inauguration, I covered the election, I covered the solar eclipse. I went to London and shot behind the scenes of Murder on the Orient Express for People magazine and was able to climb canyons in Zion, was able to scale canyons in Grand Canyon. capture all this in 360 for these different publications owned by like a parent company and then the highlight of that journey was actually being able to edit and completely post-produce from beginning to end the first ever bottom to top client of Mount Everest in 360 video for Sports Illustrated which later on was awarded a Webby and an Emmy which I'm very much a little a little weird about I don't like to share it's very like one of those things where I'm like yeah it's like it's a thing like it's just like you work hard you do you're the right person for the right place the right time but uh it tends to be something very celebrated by people when I tell them so I like to I like to not leave it out because people will get mad at me when I leave it out

[00:09:52.606] Kent Bye: Well, I was told yesterday that you were participating in this really profound experience at Sheffield. What happened in that experience there?

[00:09:59.853] Michaela Ternasky Holland: So after that amazing year at Time Magazine, 2017, I decided to leave the company just because of corporate weird things that were happening. This company got sold to Meredith... which was like the head of like more like Midwest mother type publications. There's a huge hold on innovation at the time. So I decided to move on and work at a creative agency very briefly and then actually ended up working on my own passion project. And that was a story about a woman whose face was accidentally shot off by her ex-husband. She was still alive, though, so she wears a facial prosthetic every time she leaves her home. And I was lucky enough to find this story through a photojournalist. And she and I collaborated on a 12 minute long VR documentary that I went to the woman's home and helped film and helped edit. But I had a larger idea for the actual storytelling aspect of this piece, which was included a three room installation, physical. The living room was to be more escape room style. We would recreate her home. environment, put the photos that the photojournalist had taken over three years on the wall, very much like a living room environment. You would sit by the TV, watch the woman's home videos before she was shot. You would open drawers and find poetry she had written before and after the incident. You would find the newspaper article from the incident. You'd find the affidavit her friend wrote. So very escape room-esque in the living room, but also a way to calm down and prologue yourself into her story. Then I had this idea to move people into the bathroom, which was a one-on-one intimate environment where you were then faced with eight different quote-unquote facial prosthetics, which we actually took her prosthetic, 3D scanned it, and then using 3D technology, we were able to expand the VR facial prosthetic just a little bit to fit the VR housing for the phone. for the 360 video and create eight different skin tones and eight different eye colors for all of our users to choose from. I didn't want anyone to feel like they were forced to be a blonde-haired, blue-eyed, lighter-skinned woman in any way, shape, or form. I didn't want you to feel like you were taking on her own ailment. Rather, you were just taking on a version of that for yourself so you could have that experience of not only being blind, because the woman is blind, but also being enamored with this idea that you have a face that's not your own. So touching that also had that same feeling of you're wearing something that's not your own, but it's representing who you are. And then that led, of course, into the 12-minute long VR documentary we shot, which had Google Tilt Brush drawings in it as kind of an out-to-in experience. We had 360 video and then a fisheye lens with a color grade to be able to show her hands cooking food and her hands putting... glue on her facial prostheses and et cetera, et cetera. Once you finish the 12 minute long VR experience in the bathroom, you then went into the living room and based on decisions you made in the living room, very much in that escape room way, that then triggered or unlocked your end experience in the dining room. And then before you left, you were actually giving a physical photo of yourself wearing the facial prosthetic because behind the bathroom mirror, it's a one-way mirror and there's a camera and Because it all started with a photojournalist and photo storytelling, I wanted to end with photojournalism and photo storytelling. So I don't identify the piece as VR. I identify it as compassionate nonfiction storytelling, which is very much a transmedia blend of all different styles. Because for me, it's all about balance. I never want someone to feel like the experiential mediums or the technologically advanced mediums overwhelm you. But I also don't want the classic mediums of photojournalism or videojournalism to feel dated. So for me, I really try to find that balance. And also how to make you feel comfortable in a space. I think that the story itself is very disturbing. I don't find the story at all pleasing. Obviously, the ideas of forgiveness around the story are really touching, but I want to make sure that you as a user coming into the space feel that comfort as much as you feel the discomfort in the sense that you're being taken care of, but you're also being pushed a little bit outside of your comfort zone to hear her story, to understand who she is a little more than you would just by maybe watching a documentary about her.

[00:13:56.377] Kent Bye: Wow. And is this experience available for anywhere or what ended up happening to it?

[00:14:01.380] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah, so we debuted it at Sheffield Documentary Film Festival. It was the commissioned project. We did the whole project from February to June. And then unfortunately, the family of the woman has asked that the project never be seen again just because of sensitivity for her and her family. They were all in 100% to show it at Sheffield. But obviously, when something is out there in the world, things and feelings can change. I never want to be accused of exploiting anyone in any way. So the project actually has taken like a soft fold for now. If it happens again that we do something maybe in the US, that would be amazing, but I'm not pushing anyone to do anything they're uncomfortable with. And I think that's a huge part of this kind of new era of storytelling, especially in the nonfiction realm. The reason I call it compassionate storytelling is because it's not about being unethical in a way of bringing human into storytelling and bringing people into a human space. It's about how you as a creator are being compassionate, not only to the person you're telling the story about, but also to the people that are listening or the people that are giving their time and energy to be receptive to the story, especially if the story is something as disturbing as what face-to-face was and still is.

[00:15:08.203] Kent Bye: I find... A typical approach, which is people sign release forms where you basically give over your consent to the rights to whatever you recorded over to this one individual. And then another model is that like, well, what does it mean to have shared consent or shared ownership in some ways in that? you are building the trust with your subject and that you're capturing something that's a very intimate part of her life and that she's basically consenting to document and to show it but within that very limited context and then at that point it's somewhat like she's withholding her consent of that side of the story and that you know basically that means that it has a soft fold and you don't show it but that it's like, well, if there's another opportunity and they both decide, okay, we're going to show up for another short run context that could happen. But there's not, as far as I know, like existing legal frameworks for how to like codify that, you know, what is being created is in some sort of like shared consent or, you know, I've just, for me personally, I've just been building off the goodwill of the people that I've interviewed. But as I think about, well, what would it mean to remix some of these interviews that I've done and released in some context? And what if I want to create this nonlinear memory palace? what are the frameworks to be able to have like a shared ownership to see like, well, if people don't want to participate in that, then, you know, I could maybe include what I had said in the course of an interview, but not the other. So it's sort of like, what parts do we own of an experience? And in a conversation like this, I own what I say, you own what you say. and we have a shared agreement about, you know, creating this context in which that we're wanting to put this information out in the world. But I feel like that the way that film production has existed up to this point has been very much like I'm going to just seize ownership. And it's almost like a colonial process of just like taking this. And because you have the resources to produce it, then you own it in a way that I don't know, it just feels like finding new models of figuring out how to navigate the ownership, but also the legal frameworks to be able to navigate this and make it more clear.

[00:17:04.866] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah. I mean, I think that, like, the idea of legal framework is really intense. I find the courtroom really... My stepdad's a lawyer. I find the courtroom very inhumane. I think that for myself that, like, there's still a lot of hurt. Like, I'm not saying that I'm being a bigger, better person in any way, shape, or form by not showing the project. There's definitely a huge ego in me that's like, but I spent this time, this energy, and personal funds, and la-la-la, but at the end of the day... Like if you want to be a documentarian storyteller, if you want to be like a nonfiction storyteller, especially in this realm of installation building and physical like technologies that are advanced and like something so close and so intimate that really is so beautiful for the guest, but can be kind of scary for like the person you're doing the story about. You really have to let your ego die. And you really have to say, like, take a step back and say, for the long run, I want to do more harm than good.

[00:18:00.843] Kent Bye: And for the long run, you want to do more harm than good or more good than hard.

[00:18:03.404] Michaela Ternasky Holland: I want to do more good than harm. I don't want to do as much harm as I would do good. And also for the long run, who am I as a person to dictate that? I'm no authority in this world to say that she has to show the project or anyone has to show any sort of project. to be an example that there can be more of that in the world that i think that if you want to make money don't go into non-fiction storytelling you want to have incredible real experiences and like have real human creation and real human collaboration which are some of the most beautiful things understand that is impermanent understand that humans are humans and that a project can be a human in a sense that it can just turn against you or it can move away from you and like that beauty of what it brought to you in your life when it was there and when you had that opportunity to be with it in a way is really beautiful and that that's like growth in a sense and then I've learned like yeah you do make some legal framework for yourself so don't put your personal money into a project that without some legal ramifications and making sure you're gonna get reimbursed for that if something does happen to the project. I was a young producer, I still am very young, but that's no excuse for maybe the oversight I had and the naivete in the world I had. But I do think that for people who go to court and they fight and they fight for their rights and they fight for this person and they sue that person, it's not worth it to me to continue that kind of devastation in the world of nonfiction storytelling. I understand you spent a lot of time on the project, but that is a person you're working with. So understanding that with eyes wide open is really important for anyone who I think wants to get into storytelling, especially now with things like VR and AR and volumetric capture. And even like now this like newfangled, like you can recreate a person from the dead practical thing that they're doing in like the Star Wars movies, but it's quickly turning into like also historical like recreations as well. like there's a lot of ethical issues with that and if we're not even like bringing our human selves to the table to be like hey this is inhumane or hey this is human then like the story of ethics is like a null and void it's almost like you might as well just like take it off the table if we're not even being human ethics doesn't allow you to stop being human if anything you have to be human to understand ethics right or you have to be human to have an ethical or moral code so yeah

[00:20:21.550] Kent Bye: Yeah, we're here at the Immersive Design Summit where right now there's actually a panel discussion happening about ethics. And so I think there are a lot of open questions around this and stuff that I think each of us are trying to figure out how to navigate that. But for you, it sounds like that you stopped maybe doing a lot of the VR work for now, at least, and that have at some point transitioned into working with the Museum of Ice Cream. So how did that come about?

[00:20:43.476] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Cool. So basically, I think that VR and AR still have a place in my heart, but it's like the story has to dictate the medium. And to me, like, I have a couple stories I want to tell with those mediums, but it's just not the right time. I need time to heal, obviously, from face to face. I need to, like... grow as a human being and as a person. So I was very lucky to just get linked in one day by the CEO and founder of the Museum of Ice Cream. And she basically met with me and was like, we'd love to work with you. And I was like, cool, that would be great, thinking as a contractor, thinking in six months. She called me the next day and was like, we'd like to offer you a full-time job. Here's the position. I was like, I'm not ready for a full-time job. I'm not ready for a salary. I'm enjoying myself as a freelancer. I'm enjoying being an independent artist. And she pretty much just sat with me for three hours and told me what they're doing in the company and why I should work for them. And she sold me on it. And so now I'm her creative assistant. And if you think of Museum of Ice Cream as just like kind of like the debut of the world of like experiential, there's more to come from the company that I'm really excited for that I can't really talk about. But know that like... One thing I always tell people is that, you know, the aesthetic of Sleep No More and the aesthetic of Then She Fell, those are all incredibly life changing experiences. But what about the experience for families? What about the experience for fun and happiness in the world and brightness in the world? And while Museum of Ice Cream might not be everyone's cup of tea, like the fastest way you can get someone to put down your phone is their phone is to give them an ice cream cone or give them a spoon or share a pint with them. And like, to me that's like the basis of who we are at the museum of ice cream it actually stands for movement of imagination and connection we're truly trying to bring people together in a way where before you used to have to go to spaces to understand your new phone you just have to go to spaces to understand your newfangled laptop with all these weird gadgets and gizmos and now i think there's a true need for us to go into spaces to understand who we are and understand how we're connecting with people understand even how to have safety in conversations and meeting strangers. I think that there's a huge like need in the world for more spaces that facilitate that kind of play and facilitate that kind of happiness and that joy and that kind of belief that anything is possible and so much less about like everyone's going to just stab you behind the back and murder you one day or you're going to fall in love with someone who could take a complete advantage of you. Like those are true narratives, but they're not the only narratives. And so in the way they're false, if those are the only narratives that we as immersive designers tell. So, yeah, that's kind of like my thought around that. And in a way, if Museum of Ice Cream is one step to curing loneliness, because we had our opening party last night, you know, so I'm sure a lot of people came alone. I'm sure a lot of people felt like, you know, OK, we're going to do this thing. I'm kind of nervous to talk to people. But then suddenly they were sharing a mochi in the gummy garden and they like had a weird moment where they both laughed at how ridiculous the whole situation was. But they made friends and they kind of cured their loneliness in that moment. To me, that is like way more powerful than any like... crazy, immersive, interactive, like tracked storytelling, immersive thing that we could ever put you in.

[00:23:46.419] Kent Bye: That's fascinating. Yeah, well, I had my own experience of the Museum of Ice Cream. And as I'm learning, well, I wanted to ask first just to get a little bit more context. So when was the Museum of Ice Cream created and where and then like where you kind of came into the picture?

[00:24:00.987] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah. So a little history, Museum of Ice Cream first debuted as a temporary exhibit in New York City in 2016. It was wildly popular, tickets sold out, lines around the block. Realizing that they might be onto something, our founders Manish Vora and Mary Alice Bunn decided to also open up a location in LA, a location in Miami, and a location in San Francisco, all of which have now closed down as they were temporary leases. all except for the San Francisco location which is now our quote-unquote permanent location we signed an extended lease with that company and now we're going to be housed in that place for a long time which is really exciting and so basically if you look at 2016 as like the origin story 2017 is kind of like every single sequel prequel sister location opening up and then closing down in kind of a course of the year towards the end of 2017 we announced that SF would stay permanent and so Now, all through 2018, it was kind of like this weird growth phase for the company. And now they brought me in towards the end of 2018. And now here I am, the creative assistant. So I haven't been with them super long to know like all of the pains they went through as far as the MOIC journey. But I know like starting now. into 2019. There's so much more to come and that no one should think of us as the underdogs in this community even though we seem very much like we are just a pink army ready to go with our spoons and sharing the world of ice cream and imagination. There's a lot more happening that I'm excited to unveil to the world in the months to come.

[00:25:37.086] Kent Bye: Okay, that helps. Because my process as an experiential journalist is interesting, because I'll go into an experience and I'll have a reaction and then I'll have an experience. And then it's a variety of different things that happen. And then I didn't have an opportunity to talk to someone who's in the process of architecting and creating this process of this, this experience and the deeper intention. And so I'm very interested in the experiential aspects of the design. but also I have my own concept of the experiential design aspects of it. So I wanted to get a sense of where you came into the design process. So it sounded like it had already, it was already existed, but it sounds like the evolution of this was that they had the first small pop-up, it was wildly successful, they expanded. Presumably they may, did they have any variations between those different spots?

[00:26:21.628] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Each of those spots kind of blended into whatever city they were in. So Miami was very beachy, had like banana swings, was very tropical. New York was very artistic based. It was in the meatpacking district, very much like took things from like the Whitney era, like the Whitney Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, kind of recreated ice cream art. And then L.A. was very much just about fun and play in the sense that like had just like a very... vibrant world to it, like a mint garden that was real mint. And then you'd spray the mint and like it was just very, very playful. And I think our San Francisco location might be the one that we have the hardest time with because it's the historical location. But of course, it's the location we decided to keep was the location that became permanent. So while it's nowhere near a perfect museum, they're very exciting things to come for that location to help improve some of the like some of it's like what we call like some of its more lovable features.

[00:27:18.373] Kent Bye: Well, it's interesting that you had like all of those different spaces happen all at once, because I would imagine what would be maybe even better would have been to like do all of those individually and then build another one that was building off of all the lessons. Did the San Francisco one, did it change after all the ones? Was there a synthesis process where you started to like take down some of the installations and build new stuff based upon the lessons from all those different places? Or was it pretty much the same?

[00:27:43.874] Michaela Ternasky Holland: I think all those different places were pretty much the same. The hardest part is we're going into pre-existed spaces. I know that San Francisco has gone through its own revamps, its own remounts, just like any kind of working art exhibit does. I know that the things to come for it is gonna be a huge improvement for it from beginning to end. Now that I think that the company is able to really sit back and look at like all the different things after that kind of whirlwind that happens when you first start out and you're first very successful and you're just trying to scale, scale, scale, and then scaling back and now taking a moment. I know that the future of what's to come with more potential locations, we're all going to be learning from what happened in the previous locations and what was successful and what wasn't successful.

[00:28:26.561] Kent Bye: Cool. Well, so onto my own personal experience of it was because like, well, first of all, I don't eat sugar, which unfortunately means that I missed out on a whole layer of the haptic sort of food flavor. And I think that I would have had a different experience there, but also I could imagine that. children like they love ice cream and so i just imagine how they would go into this environment and it'd be just like these art pieces but also this food and so it feels like this very sensory experience that i completely missed out on because i don't eat sugar so i think there's one part but yeah maybe we could talk a little bit about that aspect of kids love to eat ice cream. And there's so many ice cream shops all over the place. But this is a whole experiential element that they're able to add on top of that. And so do you get a lot of children, a lot of youth and the whole family, it's like a family thing that they go do?

[00:29:17.785] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah, I mean, we get arranged. I mean, I've seen, like, I've heard of a group of 16 geriatric adventurers. They call it the Adventurer Club. Drive, like, over two hours to come to our exhibits. Obviously, we get lots of families, lots of kids. A lot of millennials, obviously, for the photo-taking aspect of the museum. Then a lot of, like, really cool cats that, like, roll in from Vegas. Like, I had this really... Great conversation with this couple, just like decked out top to bottom, bling, big fur coats. And they were like having the time of their lives in the museum. So obviously, yeah, if you think of it like similar to very much like a Disney, like the overall marketing, the overall like idea of it is to kids because of just the very nature of it. It's ice cream. It's sweet. It's fun. It's a great place to take your kid. That's safe. You know, there's nothing crazy happening if ice cream's involved. But on the other hand, there's a lot of adults who like who yearn for escapism or yearn for that sweet tooth. And they like come through our doors just as enthusiastic and just as joyful as the kids. I mean, if you had a chance to peek down and see the sprinkle pool and like all the attendees that were just like playing in the sprinkle pool for hours on end, like you see the joy in their faces that something like that brings to them. And I think children and adults alike have an access to that joy while children can access it faster just because of the very nature of like them not going through heartache and then not going through sadness and then not feeling kind of those like distraught stresses of life. Do you think that when adults tap into it, it's even more like kind of that magical chemistry that happens across the whole family?

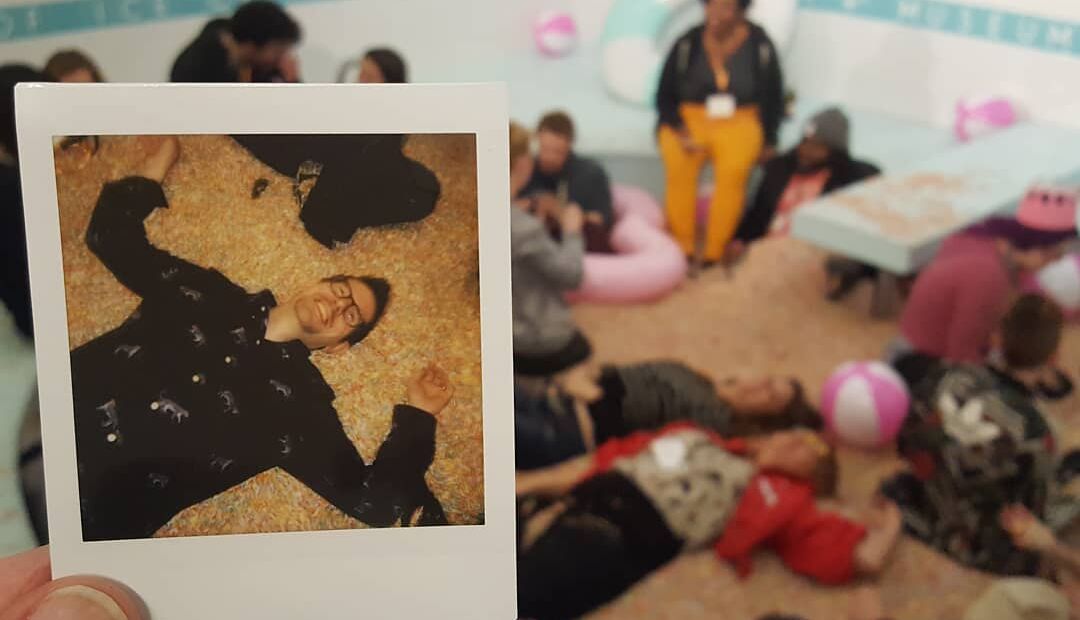

[00:30:48.043] Kent Bye: Well, yeah, you mentioned the sprinkle pool. For me, that was the most visceral and enjoyable part of all of the different installations. And I didn't go in at first because I was like, I don't want to have to deal with having sprinkles all over me. I don't want to have to, like, pick them off for the next hours. And And then I walked around a little bit more and I was like, you know what? I should just try it out. I'm just going to give it a shot. And so I took off my shoes and I jumped in and then there was some other people from the VR industry that were there. And I ended up like talking to them, but also just started talking to like a bunch of like random people that had also wanted to just jump into this giant pool of plastic sprinkles. And that I just felt myself moving my hands through it a lot and just enjoying the real visceral haptic experience. And people were like throwing sprinkles around. And so. There was such a interesting sensory experience that, uh, I don't know, like there was a part of me that someone actually took a photo and then I took a photo and shared it because it was like, I'm having a direct embodied experience of something that was really memorable. I want to remember this. And so, but previous before that, there was a lot of like photo opportunities that I was like, ah, I don't know. I don't really feel like I'm really present or really connected in this moment. Like it's not something that just feels like hollow in a sense. Like if I were to take a photo of some of these places, I wasn't having like an emotional experience in that moment that I felt was authentic. It felt like here I'm in this amazing place or this place that's interesting, or there wasn't anything that was connecting to a larger, like it just felt authentic. I mean, the word that came to mind was vapid, which is, it's harsh, but that was sort of like the impression of like, I didn't know what the deeper intention was. And it just was like, there's a certain culture of the focus on the self and the narcissism that can come on people taking a bunch of selfies that like, look how cool I am. That felt like some of that was architected for that. And I just, I'm not into taking selfies or like, but I, so I have a lot of judgments about that. But eventually I did the sprinkle poll and then I ended up posting a selfie. So it was a little bit of a journey of like, oh, this is so like, ah, I hate this. And then to the end of the night, actually posting something to Instagram, which I don't very often, but, but it was like a journey for me that I went through. And I don't know if people have a similar reaction or like what the sort of experiential design aspect of trying to create those authentic moments or creating these opportunities or what is it about that? That creates that like, yeah, anyway, that's where my experience.

[00:33:10.005] Michaela Ternasky Holland: I mean, something to really think about is that when Museum of Ice Cream debuted, there was no such thing as a selfie palace. I think if you kind of look at the timeline, Museum of Ice Cream and maybe one or two other type of things like that were the originators of the Museum of Ice Cream. And I think if you talk to the founder, she actually has a lot of frustrations with that. She never created that space to be a space that's known as like an Instagram palace or for the Instagram community. Anything, she created that space so people would get off their phones and be present with each other. And that was what the space was meant to do. It was meant to be so sensory, like you said, and meant to be so like, you know, loaded with all these fun treats and sugar to eat as you were going through these kind of really cool art installations. And very much it's successful and it was successful. It's still successful because it's such great macro design. everything's so beautiful on the macro level. There's not much detail in any of the spaces, if you've noticed, because that's what the focus was. The focus wasn't meant to be like, oh, let's just go and do this really cool little treasure hunt exploration of all these little details in the Museum of Ice Cream. It was, let's just get this big explosion of colors, explosion of these amazing moments of these crazy unicorns you can sit on, things that you weren't really able to do in 2016, if you think of our world as 2016 world. Now, Flash forward, we're in 2019, completely different world. People totally realize that's a cash cow and they've like created, dare I say, bastardized versions of what that is to be. But I think, I don't know if you took the time in your tour to really listen to what the guides were trying to say. And I know those tours were a little frustrating for the guides because people were obviously very tipsy and just like wanted to take a bunch of pictures, but really like... If you came back on like a more sane day, the guides try to really tell a scripted story that involve activities in each space. So for example, like in the rainbow room with the unicorn, we try to ask people to pick a color and then only step on that color as they leave the room. And that might seem really trivial, but again, it's just a way of like, you know, we call that really shiny room the unicorn stable. We like try and like ask people to text their cherry on top and let them know they're thinking about them in the cherry room. You know, we try and like really bring out more script and narrative and characters with our guides who are not only trying to do food management, room management, safety management, and then also story management. And that's a lot for like a 20 year old going to college to do. But those kids show up every day and do it and do it very well. I actually think for like the eight hours they're on shift. And so while there might be, like you said, like this kind of vapid experience if someone was just walking through the spaces and eating the food, I think what makes the experience to me really real and really human is the guides in those spaces. And like when you take a moment and actually listen to the stories they're trying to facilitate in each of the spaces, you actually have like a very rich experience whether or not you're eating the food. And that's actually something that I'm really passionate about bringing into our newer spaces is obviously more detail design, but also more narrative and story design and more characters that they can really like feel attached to and feel like there's a mission or feel like there's a journey or feel like they're a part of a certain collective or they're celebrating a certain thing. And I think that will just really help elevate the experience as well beyond just like the amazingness of the sprinkle pool, which is obviously like what we're well known for.

[00:36:24.076] Kent Bye: Yeah, well, what happened was that I started into the very first room, and so I started with that room, and there was sort of a flow, and then people started asking each other the questions on the curiosity cube. I got handed this card with questions asked to people, And none of the questions were very interesting to me. I mean, in terms of connecting to people, like I do a podcast where I like ask people like super intense questions. And so there's a bit of the art of conversation that I'm really tuned into. And I felt like actually those cards were taking me out of that experience in that moment. because all of a sudden people are talking about stuff that they're probably not really actually interested in and it became this whole like game where people were trying to get enough of the things crossed off on that card that those cards functionally served as like people looking at their phones it was like i was present in the moment and then everybody in my group all started doing that and i was like i'm not interested in having this experience right now I don't want to talk about my favorite ice cream because I don't eat ice cream. I'm like, I don't need sugar. So there's a bit of like me not connecting to the deeper intention of connection at that moment. Like I ended up having connection with people based upon these emergent moments in the sprinkle pool that was more organic, but it felt like I could understand the intention of having something like that. But for me, it took me out of the experience. And then I kind of like, I was like, how much do I want to go through this entire journey with something that I'm not connected to in that moment. And also I was like thinking about doing interviews. It was like sort of jumping in between different contexts, but that was my experience of that moment.

[00:37:56.704] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah, I think I feel you in that sense where because I come from a journalism background, I also get, it's like a term I've heard and I like a lot. It's the idea that you really like to take a step back and not be in the thick of it because you're observing or you're scoping out another interview of some sorts. And I think that one thing to keep in mind is that people come to the museum ice cream from all walks of life. And so those connection cards, we couldn't say who was all coming to the Immersive Design Summit and we couldn't necessarily tailor what we would call like a lesson to like only advanced socializers. And so what we really do is we try to play to the common denominator, right? So like, We get people who come into our spaces that like all day, every day, live on their phones and have really no idea how to have conversation with someone else. You, on the other hand, you are obviously like a very much advanced socializer. So things like high fives, things like asking people ice cream names might seem really trivial, especially in in the sense in the real world of journalism or what you're trying to do with experiential storytelling. But for us in the Museum of Ice Cream, it's very much narrative that we can tell and get away with and make it fun and make it interesting for people who come from maybe a common realm of like, everyone is direct messaging me all the time on Instagram, and I have trolls on Instagram constantly telling me how fat I am, or I have that guy from school constantly bullying me and attacking me. So I think that there's obviously, again, going back to that sense of we used to go to stores to help understand our technologies. In that moment, I think we were maybe playing to the beginner, intermediate group of people who might come to us to be like, I'm going to have a good time tonight, but I'm not really sure how to get that started. And so that's kind of where those connection cards really play to also to kind of help everyone understand that we're not taking ourselves seriously as Museum of Ice Cream to be like, wow, we're supposed to have this really deep moment. No, it's supposed to be like, hey, you're here to eat ice cream. You're here to have fun. Like we totally get that. Let's have fun and let's eat ice cream. Let's have 10 strangers give you each other high fives. I do agree. I think that some of the prompts could have been a little stronger, and I wasn't involved in the writing of them. But I think that, again, if you think of it like if you went into some sort of lesson or workshop and, say, you totally understood the iPhone 6 forwards and backwards and upside down, and then you went to a beginner's course of how to unlock their phones, yeah, of course you're not going to feel engaged in that experience. But anyone who really has never had an experience that deals with an iPhone 6 unlocking their phone can just be like this momentous moment of something they've been trying to figure out forever. So I think everything you said is 100% valid to the advanced socializer you are. And then 5,000%, I'm sure there was other people that felt that way to you. But for us and the types of people we have come into our spaces, families who never talk to each other, families that never have dinner together, families who might just, you know, do it for the gram. We're really trying to like bring them together and bring kind of like those common denominators of people who represent maybe like the 90% of us and not like the intellectual 10% of us. Does that make sense?

[00:40:54.284] Kent Bye: No, yeah, totally. And yeah, that's what I say. It's like, I have my own experience of things. So it's hard for me to like make grand judgments about my own singular experience of that moment in time, but trying to understand the deeper context and the audience that you're trying to serve, because I, I do see that there's a lot of isolation and loneliness that we have. And you said that that's a big intention for how you're trying to break out of that. And so how do you measure your success as to how you're connecting people? Because it's like, you know, having the connection cubes is one approach. And for me, I'm thinking about like, well, I think about in terms of like, there's things that are happening in the minds, the communication, and then there's things that are happening, just like a shared embodied experience with other people. And then like, what are the components of like, really feeling like you're connected? And like defining that and then figuring out backwards, like how do you actually cultivate that connection? Because I'm not convinced that like a card and having the prompts is the best way to connect people. Like, I guess there's a bit of like, what is the definition of connection and how do you measure it? And then from there, like, how do you sort of design towards that goal?

[00:41:57.591] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Well, connection cards aren't something we do in the museum at all times. It was something we do for event. And we did a Valentine's Day version for bingo. So usually the experience is you go through the experience sans card.

[00:42:08.542] Kent Bye: Oh, you do?

[00:42:09.964] Michaela Ternasky Holland: OK. Yeah. So that was like an extra layer we wanted to give you all. Because again, we just we didn't want you to feel like you were just getting a run of the mill like museum of ice cream experience. We wanted to gamify it. We wanted to make it feel a little poppier and like give you kind of all a mission. So that's why we had those bingo cards. We also did it for Valentine's Day and people loved it.

[00:42:29.401] Kent Bye: So there's a bit of a game of trying to complete all the things you mean?

[00:42:32.444] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Totally.

[00:42:33.225] Kent Bye: But it's like a social game because we were told like, if you complete all the boxes, then you win something at the end. And then there was a part of me that was like, ah, well, I'm probably not going to want what they want. So there was no like deeper incentive for me to do that. But it seems like you're trying to create these interactions that are having a gamified element, but it's through the interactions of the social interactions.

[00:42:53.783] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Right, exactly. And again, for example, I don't think you would have just buy a ticket to the Museum of Ice Cream and come into our space on your own accord. So I mean, obviously, the fact that you felt like you had no interest in getting whatever we were offering, totally fine. But I do think that there is that sense that people come to the Museum of Ice Cream because they know it's a very specific experience. And so they want everything and anything. They really buy into the brand. So you asked a couple of questions, and so I want to kind of address those. How do we measure connection? I think it's really seeing how the group themselves are engaging with the guests or the guides, how the guests in each group are engaging with the guides, because the more that they're engaging with the guides and listening, the more the guides unlock really fun activities that make it very obvious that people are actually engaging with each other in the spaces. Dance parties, Simon Says, you know, telling each other secrets in the unicorn stable. Like, things that move just beyond, like, I'm on this unicorn taking a selfie, or I'm on this gummy taking a selfie. It's, like, very much so, like, we have cameras set up in every room for safety, and so if you look at the kind of, like, the string of cameras, you can see people, and you can see, okay, like, that group's not as successful in what they're doing as far as connection-wise, and people, we go into groups of, like, 12 to 15, so they come in as... mainly as strangers, you know, like people only come in groups of two to three usually in our experience, unless it's like a big birthday party. And so we're seeing like, you know, strangers like playing Simon Says all together with people they've never even met before. Or we're seeing strangers, you know, make like scream tunnels with each other. We're seeing strangers help each other write messages and dream. And to me, to us, that's like creating connection or even just a family instead of it just being a family of people that are going together completely silent and like eating the food when we're seeing like a family engage and connect and like really interacting with each other and the kids running around and having a great time to us that's all like forms of connection so like to me those are all like quote unquote like you're asking like how are we measuring success or connection we're seeing kind of those like true like what we were meant to do play as people seeing those like aspects of play come to life like physically through talk through play etc etc in the groups and our guides will know oh my gosh that was an amazing group you know i felt really connected to them they were so enthusiastic they were listening to the rules but still like engaging with the game so that's like how we measure all of that you know and i think that you also mentioned like human connection and what that is and it's just like It's just one of those interesting things. I don't think that we can bottle it up and put it into some sort of serum and drip it into everyone's drink. But I do think, like you said, there is a lot of isolation and there's a lot of awkwardness. People tend to be very awkward nowadays in a really interesting way. They first come into the space, it's like, The sprinkle pool is the first thing they start with and it's amazing to see them go from standing in line, no one's ever really talking to each other, everyone's on their phone, they jump in the sprinkle pool, they have this amazing time and that really breaks kind of like the barriers of what we can then do with them when they come down into the vault into the other spaces. And from there we kind of, like you said, so you kind of did, you did your experience backwards where you ended at the sprinkle pool.

[00:46:02.832] Kent Bye: That's where they, that's how they told us to do it. Yeah.

[00:46:05.441] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Totally fine, because it's like the event wise, that was just like how we were working on the flow from the mezzanine down to the vault. But actually, if you come again on like a real day, we start our experience in the sprinkle pool for now. It might change, but we start our experience in the sprinkle pool. A, it's most Instagramable spot. We like to get it out of the way. People usually sometimes go to the space if we do an opposite flow day and they're like, where's the sprinkle pool? We want the sprinkle pool. So just to get them focused, get it out of the way, get their pictures. But also, like you said, you had a visceral moment in the sprinkle pool or something really interesting about that design aspect of what that is and so getting that out of the way for people and kind of giving them this clean slate this kind of cleanse of being like okay now you like are really bought into what we're trying to do now will you play with us because when was the last time you swung in a swing when was the last time you know you partied like a rock star with a gummy bear when's the last time you did the sprinkler when's the last time you rode on an animal cookie ride like outside the grocery store like That's constantly what our guides are reminding people. When was the last time you just thought about your cherry on top and texted them that you were thinking of them? Or sat them right next to you and told them that you loved them or that they were your cherry on top? It might seem very trivial, but in the world that we're living in, in the go, go, go aspect of the workaholicism, especially in San Francisco, it's truly, I think... a sweet light that we're trying to bring and like to me that's like all you can really do like with Disney it's a whole nother sweet light that they're bringing into the world and with us like we also want to bring a sweet light into the world and like to me that is nowhere near perfect it's nowhere near perfected in the way that like might feel like a perfectly timed immersive theater experience like Sleep No More or Then She Fell But it is something we are willing to figure out, and it's something that someone was willing to say was needed in the world. And to me, the beauty that a place like that was even built, and the beauty of the fact that people still want to come to that space, and the fact that the beauty is we don't have a focus just to take photos. We don't just have a focus to get people in and out and to rush them through the space. It's really a focus to be like, stay, hang out with us, have fun, eat ice cream. Because that's what that whole big lobby area is about. It's not about buying. It's not about merch. It's just like... be here as long as you want after you're finished with your tour and we will love and welcome you as family.

[00:48:21.828] Kent Bye: Yeah. What I'm taking away is that the order and the structure in which that I went through, it was not the intended design. And so I think that was a part of that, but also that it being a party and event and other conversations that were very vital happening. But I think that if I would, well, I think if I would have experienced again, outside of the context of like a bunch of super advanced immersive design people that are to see it with people that were actually kind of the intended audience. I think I'd have a different experience of that, but that you mentioned before that you're looking at like three things. One was like movement and imagination. What was the third thing?

[00:48:55.391] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Connection.

[00:48:56.372] Kent Bye: Okay, so movement, imagination and connection. So we talked about the connection a little bit, the movement, you're actually moving your body through a space. And because you're a dancer, you know what it means to sort of have a spatialized experience of what it means to move your body is a form of art. But how do you see that movement is a part of your design strategy of what you're doing here?

[00:49:14.855] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Well, I think even just the type of, like you were saying, hypersensorial experience you have with the sprinkle pool. Like the idea of the bodies that we were created, it's not like a seated, you're just eating ice cream experience. Because if we wanted to just create another ice cream parlor, we would have just created another ice cream parlor. And that's kind of what that is. But obviously, our space is you have to stand up, you have to walk. I mean, obviously, we have ADA. And we have those kind of like elevators and things like that for them. But this idea that like you are going through kind of like almost an Alice in Wonderland like journey. And I think movement. It's also, it's a double entendre in the sense that like we want people to be moving in our spaces. We're constantly having dance parties. If you could tell like our guides were constantly trying to get people to dance or get people to kind of just like loosen up. Cause I do think there's like a lot of tension we hold in our brains than physically manifested in our bodies. And people who aren't really like used to kind of letting all of that go in both the mental and the physical world, have like a lot of anxiety and stress and frustrations and I think that just kind of like not taking yourself too seriously is what ice cream is about you know like the idea of ice cream is like oh I'm gonna eat a whole pint of ice cream tonight before I go to sleep or hey we're gonna go share an ice cream fuck it let's have some ice cream like ice cream itself is like let's not take life too seriously like let's enjoy life like you're not gonna eat ice cream because you hate eating ice cream, you know, and obviously you'd have a different experience because you don't eat sugar. I personally am lactose intolerant, so there's obviously like vegan ice cream or there's actually a lot of things I can't eat in the experience, so I don't. But I do think there's this like really fun aspect that you'd like moving your body through the space and also dancing your body through the space or like making your body come to life by even just touching the sprinkles. All of that is one form of the movement of what we're trying to do. I think getting people off their phones in such a cramped way, you look over your phone or you look over your laptop, it's a very cramped environment, giving them space to really lengthen out and touch things and feel things or reach for things is really important. I think any reason why people love going to immersive or interactive, it just allows them to move in different ways, whether that's move through a space or move through a story or talk to someone they would never talk to. That's like in of itself a form of movement because you kind of move your body as you do that, move your mouth as you do that. But also movement in the idea that we are a movement. We are trying to kind of like bring this new world view of just like, hey, The world sucks. We're not trying to say the world doesn't suck, but what we're trying to say is that like there's still light and happiness in the world and we want to create a space for you to feel safe, to have fun and celebrate the world that you love living in as well. And so that kind of movement as well through the world, like again, not that sleep no more and then she fell are incredible pieces of art and they're not incredible like, you know, and more like the tension experiences and the drunken devil experience is not that all of those don't have a time and a place. But things like the Museum of Ice Cream and the Color Factor, I think, need to have a seat at the table because they're speaking to a very interesting genre of audience and demographic of audience that I don't think really have a seat at this table right now. And I find that really sad and I find that really frustrating. you know even just off-handed jokes of like yeah like and now we're gonna go take all the selfies in the world it's like right you're already setting yourself up to not understand that someone like in their mind's eye created an immersive environment in 2016 before immersive was even like a thing and there was a design aspect to that and there was a thoughtful aspects of that and it was like kind of the beginning of food experiences and like you know there's a lot of really amazing things that have happened in this industry because of places like the museum of ice cream and quote-unquote selfie factories and yes brands do it all the time now and it feels very much a bastardization of just commercialization without artistry and work But that doesn't mean every single person in that playing field is just all about that. And we're definitely not all about that. And I I actually like I play in that realm where I come from that indie artist journalism background. So I'm like, oh, but real stories and real people. But I also see like. I want to bring happiness to kids and joy to families. I come from a Disney background, a Legoland background, a SeaWorld background. And I'm sure those places are looked on as very much trivial and like the idea of an adult theme park or a Six Flags. How are you going to create a theme park that doesn't have an upside down roller coaster? Well, they can do it and they can do it really well. And so I want to like I want to caution or I want to like just give warning to anyone out there who really trivializes like selfie museums and palaces, especially ones that are more family oriented, because everyone should feel accepted and loved in the immersive design world. We are like a very young, tight community. And if anyone feels like they don't have a seat at a table, then we're already starting to do something wrong. And I caution all of us to take a step back and try to really re-circumvent and understand that all art and all immersive and all design should all be respected equally 100% no matter what.

[00:54:17.465] Kent Bye: Yeah. And I have to say, this is my first like selfie museum that I've ever been into. I cover more VR and so it's like coming into the immersive space. But I have heard a lot of just the talk around and there's a bit of a cultural bias that I was probably walking into where there was a bit of a dismissal of the validity of something like that. And what I could understand and actually seeing it would be and I think I saw this to a certain extent of people taking photos and selfies and like because we didn't have the sprinkle pool or whatever first to get it out of the way. Then when I went through it, then people were taking a bunch of selfies and stuff. But but there did seem to be a bit of like people have a lot of stories about what this is and what it's about. And I think the deeper thing is like what the deeper intention is, because it seems like that the Museum of Ice Cream is very economically successful. It's a thing that people are really resonating with.

[00:55:06.728] Michaela Ternasky Holland: And buying merchandise for like that's huge. Like, I don't know if you had a chance to look through our merchandise shop. Obviously, it's a lot of partnership collaborations, but we sell a whole ice cream line in Target from beginning to end. It's our own flavors of ice cream. We have these pinata plushies that sell like hotcakes off the shelf we have a whole like sephora collection like yeah and that's very branded and commercialized but like the whole talks that have been happening is like how do we collaborate with these brands and how do we collaborate with commercialization and like without selling ourselves short and it's like fully embrace you are and if people buy in they'll buy in and i'm kid you not we were sold out last week for no reason whatsoever but the fact that people still buy in and that doesn't mean it's a bad thing i mean people buy into disney people buy into sleep no more they're successful shows we just happen to also be a successful show so i don't know what exactly else to say to that but yeah i think that that's like a very important aspect of like what you're saying in the sense that like people obviously still are hungry for it so they come

[00:56:12.233] Kent Bye: Yeah, and imagination was another big part. How do you catalyze imagination? How do you use imagination as part of your experience that you're trying to create?

[00:56:21.119] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah, I mean, our founder, the whole reason there is a sprinkle pool is because she used to imagine the ocean as an ocean of sprinkles and what it would be like to swim in an ocean of sprinkles. So it literally is founded on imagination. I mean, who else would think of like riding unicorns in a rainbow room with like a totally retro disco unicorn stable? And while that doesn't all read on film or on camera or on Instagram, there's a story behind each of those spaces. Oh, why not be a kid again outside the grocery store when your mom used to eat together her last 50 cents of change so that you could ride the little truck? Oh, why not do that as an animal cookie in a carnival ride? What would it be like to have a garden of life-sized gummy bears and macaroons and So each of our spaces is breathing imagination into the real world. Is it done super well where you want to spend hours and hours in each space? Maybe not, but it's done to the point where like, hey, anything is possible. Anything is possible. anything is possible, even a pool of sprinkles, you know, or like anything is possible, even if you wanna go swing on a banana swing under a canopy of bananas, you know? And it's just that absurdity of like just taking away every boundary that could possibly exist in the world of saying like, that's ridiculous and that's stupid and that sounds weird and why would you ever do that? And oh my gosh, like, don't ever like have another original thought again and kind of like how we beat down even children today in schools like gotta study for the test gotta like be a lawyer gotta be a doctor like no like why don't you just go and create an ocean of sprinkles of your own and become a multi-millionaire And that's huge. Anything is possible. And anything should still feel possible in this day and age. And I think that's what Disney inspires the world. People like my co-two with South by Southwest World, they inspire the world. And that's what I think we're trying to do, even if it's not necessarily to the world of bourgeois middle class people who can afford like all of this like knowledge and wealth and understanding of education in the world, but also like to the high school kid that goes to school in Oakland that saved up all their money to go to the Museum of Ice Cream with their one friend. And that friend ditched them for the day. And so they had to go through the whole experience themselves. But every single one of those guides became their new best friend.

[00:58:35.337] Kent Bye: Great. And for you, what are some of the either biggest open questions you're trying to answer or open problems you're trying to solve?

[00:58:42.096] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Yeah, I think narrative design is my biggest one. I really want to see, like I think I mentioned before, like really thoughtful characters, not just overlay of characters. I really want to see thoughtful design and story aspects of the experience. I think there's this movement toward making ourselves more of like a magical kingdom and less of like a pop-up selfie palace. And so a magical kingdom needs to be like infiltrated by its citizens so like what do those people look like what do they feel like why do they live in this world without making them feel trivial or making them feel cheesy or making them feel like they were just thrown into the environment for the sake of having them in the environment and then also i think making our spaces feel more comfortable i think right now they feel very blockish very corner very like vinyl on a wall and go take a picture which again like someone who does something from scratch is like a kind of a guerrilla style, like that's kind of what you have to do to make your dreams come true. But now like, you know, the company's a little more well on its feet. So I want to see us do something more exciting and more adventurous with making the space feel more comfortable.

[00:59:44.336] Kent Bye: Right. And, uh, and finally, what do you think the ultimate potential of immersive experiences are and what it might be able to enable?

[00:59:54.662] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Ooh, that's a deep question. I think that there is this insane potential for everything and anything. I think from the time you're a child and you build yourself a fort and you pretend X, Y, or Z in that fort, there's an immersive experience happening. We are ingrained in immersive experience. The world itself is the most immersive experience you can be a part of. I don't think any type of theater or VR or AR will ever... ever replaced true traveling and seeing a different culture other than your own and living in that culture but i do think that there is a way that we can make things accessible to people who might not have access to doing things like traveling and expose them to new stories and new worlds that they haven't been able to in the sense that how tv kind of broke the mold and like bringing a whole new form of entertainment and a whole new form of education to the world I think immersive and interactive and doing it really well for people is going to also kind of break that same mold that TV did when it went from TV to radio and now immersive interactive.

[01:00:52.711] Kent Bye: Right. Is there anything else that's left unsaid that you'd like to say to the immersive community?

[01:00:56.752] Michaela Ternasky Holland: Uh, not at all. I just want to say thank you for anyone who's listening that does your own work or is just a supporter of like the field. Thank you. Because, you know, as humbling as it is to be able to be a part of this field, it's also more humbling to see the work that everyone's doing and to see the supporters who buy tickets, who come, who support in any way, shape or form, but even by listening to podcasts. So. we thank you we thank you that you give us a place in the world we thank you that you give us a home in the world and i just hope that we don't disappoint and i hope that we really again just think of you as a guest first and egos last and i think that when we do that we can create some of the best work awesome beautiful well thank you so much for joining me so thank you no thank you ken it was great to meet you i'm so excited to um be on this podcast and i feel very honored

[01:01:43.646] Kent Bye: Thanks again for listening to this episode of the Voices of VR podcast. And if you enjoy the podcast, then please do spread the word, tell your friends, and consider becoming a member of the Patreon. This is a supported podcast, and so I do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring you this coverage so you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Thanks for listening.