I spoke with Maartje Wegdam & Nienke Huitenga Broeren about Lacuna as a part of my remote coverage of Cannes Immersive 2025. See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

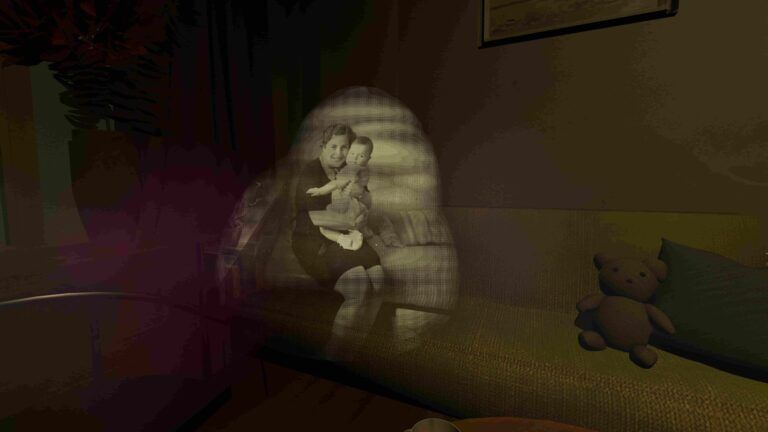

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR Podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR Podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So continuing on my remote coverage from Khan Immersive 2025, today's episode is with a So I'm going to read the description of this piece just because it's a bit hard to describe. So in the emotional journey that follows, you accompany Sonia through skewed memories, elusive images, and reimagination towards one moment of loss and grief during the Second World War. Combining conversations with Sonia, mesmerizing 3D modeling, animation, and personal footage, Lacuna explores who we are in relation to who we were. Meanwhile, you will find truth in imagination, beauty in the unknown, and an active unconditional love. So in this piece is kind of exploring memory and reconstructing those memories. And it's about a trauma that happened during the World War II where Sonia's parents were taken away to a concentration camp and they died in the Holocaust. And so it's a story that is kind of leading up to that point where. Sonia doesn't really remember her parents and then her parents buried these napkin rings in the ground and then like someone found those rings and then they returned the rings and so upon the return of these rings it opens up all these questions around the story of what happened to her parents. Sonia had all these letters from her parents to kind of fill in the gaps as to what had happened and she's kind of dealing with this spotty memory of trying to grasp onto what the story even is and so a lot of the process of the story is this kind of documentary process that start to have this kind of whodunit or true crime type of situation where you're just trying to figure out what the actual story is and what actually happened. So there's kind of this investigation process that the filmmakers are going on, but there's kind of weaving together Sonya's story, her parents' story, as well as the story of the craters. And so it's a process of weaving together this multi-threaded story with different emotional peaks, but also this kind of 3D jigsaw puzzle that you're putting together. The virtual reality aspect is that you end up walking around the space and that there's a lot of visual metaphors for this fragmented memory and hazy memory where things are kind of blipping in and out and it's not really clear the spatial context and eventually it'll kind of crystallize and you'll be transported to these different moments. from the past. And then on top of these 3D reconstructions of these rooms, it'll be like these photos and these artifacts, as well as the narration. So it starts with a narration and they're building up all the sound design and then building up at the last part, all the different visuals and 3D and worlds and kind of interaction design to explore how to tell the story in more of an immersive, interactive way. And it kind of gives you this feeling of trying to decode or understand this dream. And I actually found myself going back and watching it again, just because it was a little disorienting and fragmented in a way that it's a story around the creators trying to find the story. And so you're also in the process of trying to understand these different through lines as you go through the piece. And all these kind of foreshadowing aspects. So we talk around in this conversation, how there was a lot of like restructuring of the story and how to like unfold the complexity of a story, but also this kind of multi-threaded nature of how to tell this story within the context of VR that allows you to have these different interactive aspects that are symbolically reflecting different themes that are also being covered within the story as well. So we'll be covering all that and more on today's episode of the Voices of VR podcast. So this interview with Marcia and Ninka happened on Monday, May 26th, 2025. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:03:46.092] Maartje Wegdam: My name is Maartje Wegdam and I'm one of the directors of this piece, Lacuna and the writer. My background is in documentary film, so I don't come from a VR background. However, over the last years, I've been kind of opening up to explore more other ways of storytelling, like to expand the documentary form, so to say, the genre. And this is my first VR. And when, like early on in the process, the story really led me to think that this may be a VR. And then I felt like I had to surround myself with people that had more experience with the medium also. So that's how I met Nienke. Hello, that's me.

[00:04:31.951] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: I am Nienke Huytega and I'm a director, also a producer, and I love to make immersive experiences. So VR is one of them, one of the media I work with. I think the first Big piece that I debuted with is Rositne, a nonfiction short VR experience about MH17, the plane that was downed above Eastern Ukraine, 2014. And from there, I quite recently premiered a more, let's say, an audio piece at IDFA DocLab Drift. So I kind of navigate different styles of media, styles of experiences, and Lacuna, came about, I think, Marcia and I met in 2022 or maybe slightly earlier.

[00:05:20.404] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah, no, it was. Yeah. Yeah. I think summer of 2022, I think. Yeah.

[00:05:27.470] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah. And yeah, we really had a click. Marcia already started in 2020 with this project and perhaps slightly earlier. But I think the first recording with Sonja is 2020. Yeah. And when I met her, There were a few ideas about concept and were a few ideas, let's say, early sketches of what maybe could work. But the gold, of course, was the conversation recorded with Sonja. And that's where I got really enthusiastic. Sonja is a great human, very nice, sharp woman with a lot of humor and very courageous to have this conversation with Martje. And that's where I wanted to step in.

[00:06:11.124] Kent Bye: Nice. And maybe each of you could give a bit more context as to your background and your journey into working with immersive media.

[00:06:17.927] Maartje Wegdam: I started out well, like how far back did you want to go? So Well, I came from journalism and then I rolled into documentary film. So I think for me, not like the immersive media, but the documentary genre is at the core of my practice. Still is, I guess. So, yeah, I attended the New School in New York for documentary graduate studies. And then after I started making work, or well before already, but yeah. So I made a couple of shorts and then a feature film called No Place for a Rebel. which premiered in 2018, I think, which was about a former war commander who was abducted as a child and got back home as an adult commander and a perpetrator of the crimes he once was a victim of. So I guess I tend to explore these ambiguities. in my work and instead of really like seeking answer to these questions, like explore the questions themselves in the work. And I met Sonja in 2000. Well, in the meantime, I also started teaching at the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences. And through that teaching, which also had an immersive component, but also through my own practice that, you know, I just started to do little experiments, not like for like showing, but like for myself. And I did a residency in immersive. So I started to kind of experiment with other types than the long form or short form linear film. And yeah, then I met Sonja, the main character of Lacuna. And I met her when she just had received back three napkin rings, the rings that are also in the piece. So I learned about these rings through research that I was in touch with for another project. and she told me you have to contact Sonja because this might be something you know there might be a story behind it and when I met Sonja and she told me that she really didn't have anything to say about these rings that the thing that I wanted to know like what's with these rings how did you get them what's the story behind them we started kind of looking at these rings with the same questions but from very different backgrounds and then I felt like soon that this was a story about not having a story, about all the gaps that are there, but I just couldn't articulate. I felt a spatial component to it. I felt like it should be something where you can maybe walk into someone's... I really wanted to be in her brain, in her head, you know, and see how that feels or feel how that feels, like not to be able to retrieve these things, but I didn't have, like Nienke said, I didn't have, like now it's like comes together nicely and feels like it's very logical, but I didn't have a way to articulate that. Like how I knew it had to be snippets, but like what's the language for snippets, you know? You can do that a thousand ways. So I just knew it needs to be snippets and you should be able to walk through them or to be in them. But so I did feel from the story that this should be a VR piece, but it's not that I wanted to make an immersive piece. And that's why I found this story. So I think, yeah, for me, it's more... probably a next story will require like different techniques or different. Well, I'm open to a completely different form, the language that will suit that story. So I think that's my approach to immersive media. To find the language for the that part of the story that you then want to tell.

[00:09:59.955] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah, I was trying to figure out what was the first immersive experience while you were explaining your your journey margin. I'm not quite sure, but I actually think the moment I started feeling attracted to this type of experiencing, I think it started with a Duncan Speakman piece, maybe, an audio piece by him, a subtle mob, which then he still made under the collective of We Are Circumstance. And I'm not sure what the title is. But he created it originally, I think, for the Edinburgh train station. And then they brought it to Rotterdam, I think. Must have been, I don't know, 2013 something. Because I originally am trained at university studying film, but it's a very theoretical study. So I mostly studied film culture, film history, film analysis. But I graduated around 2010. And, you know, the internet was kind of shifting, the type of interactions we could have with the internet were also kind of becoming new. YouTube came on and a friend of mine convinced me that, oh, Nienke, maybe it's interesting for you to work with this cool guy, was a visual artist who wants to do a transmedia story around a modern day Icarus, an engineer building his own wings. I had absolutely no art academy training, but I was so, I don't know, I was kind of curious. I was kind of curious to kill the cat. So I got into that project and it's kind of my radar for other, like these fringe experiences that kind of feel like they come from film, but they behave differently. And I started to be, I guess, quite a student at IDFA DocLab. Like I really went to all of their exhibitions since my graduation. But I think when that piece from Duncan Speakman at Rotterdam Station was like an audio subtle mob, you play a character, there are four characters in total, but you are with a group of 30 people at random play that character. And it was a very open narration. So it's not a narration where the plot is particularly told to you, but you're part of the last bit, like there's a bit of openness. And I just got really intrigued with, you know, your own agency, the space you could take, And I think VR came in a very natural way on my path because it's the type of medium that provides a bit more control than a train station. It might be more solistic or more solo. But I think that openness where space also creates a carrier for your thoughts, for your presence, for a memory in this case, for Lacuna. I kind of think more from that will come. I'm not sure how. But yeah, kind of this alchemy kind of happened somewhere between 2010, 2015, I think, for me.

[00:13:06.348] Kent Bye: Okay. So I just had a chance to watch through Lacuna, which was premiering there at Khan Immersive in 2025. So it's a piece that has a lot of fragmentary nature of it. It's almost like a true crime in its structure in the sense that you're kind of discovering things, but it's also a story about how there wasn't a story until the memories came. And so there's an unfolding of those memories, which I think you mentioned, Marcia. And so... It sounds like you're meeting with this main protagonist, Sonya, and then the first meeting, you're not really getting a lot, and you have to keep meeting with her. I'm just curious, at what point did you have the breakthrough where you had enough to know that you could tell a story rather than... to try to tell a story about not having a story, which then ends up being kind of a hard story to tell because then nothing happens. And so it seems like the story was unfolding as you continued to pursue it, but in the absence of the pursuit may have not really developed or those recollections may have not happened. So just curious to hear a little bit about that process of going back. And at what point did you know that you had enough to tell a story?

[00:14:15.515] Maartje Wegdam: Well, I think I knew early on that there was more to it than she was telling me. So of course, in the piece, she's like, I don't have a story. So basically, that's the end of it. But it's not. But she did tell me that she had these letters from her parents. that I couldn't read for the first year and a half because of COVID. So I knew that there was this stack of letters, which I anticipated was like this diary, basically, during the war times. And so I knew that there was the parents' thread, basically. And although it was not her real memories, I also knew that there was the napkin rings and what else? The photos, which is also not her memories. But it's like, again, like something that is imprinted in your head from pictures that then becomes this memory. So I was really interested in the nature of these memories. And so it was never only about what is there, what is not there. It's just all these memories. different categories of knowing somehow of memorizing that i knew from early on that she embodied all these elements it was just that she was not convinced or she was not giving me access basically to that part of her so she was also thinking i think partly telling me i don't have a story because she also felt It's like kind of, yeah, survival skills. You know, I haven't been in a camp. You know, there's others my age that had way worse because they grew up in the Netherlands after the war. They have stories. And my story, I don't know if you know anything. So it was also a way of her to kind of redirect me basically so I didn't know exactly what the story was and when I would have enough but I knew early on that there was more to it so that's why I kept coming back and then she'll be like yeah I can tell you a little bit more but it's really not about me and then she'll be telling like a lot but I really I don't want to be the main character you know it's about the rings and the people who found the rings and so it was kind of balancing where the heavy point, you know, the core point.

[00:16:22.740] Kent Bye: The anchor.

[00:16:23.601] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah, the anchor. And so soon we diverted from, you know, what has happened with the rings and what has not happened. So that was basically one conversation because that was it. But then there were all these letters that I suddenly could read. And then, you know, there was all these, I mean, it was more the other way around. Then I knew how rich the story was and how many stories you could tell. with this lady in about this life, you know, there was letters even throughout. They sent even letters from the camp in Westerbork. So there's like other historical lines and the whole adoption process, like how she got to Suriname. That's really another story. So there might be even more stories coming from this. But Then it was more the question of how to distill the core from all these materials. And then it was basically getting back, making the connection between not knowing anything, like the not knowing that was still really big, you know. So I think also that we had a lot of conversations together, Nienke and I, like how do we make you feel also that that's big? You know, if you have a flat screen... Of course, you want to show nothing. You can show a few seconds of black screen and that's that. But here you can actually show the vastness of that void, basically. And to contrast that with what is there. And then I started kind of really like extracting all these lines. There's the line of the parents' storyline, what happened to them. And how did they feel about having to say goodbye to their children? That's their line. Then there's Sonja's storyline, which is from her youth, not knowing. First, of course, like being sent away to Suriname, but then not knowing what happened and then reflect like getting back to it at different stages, like in the 60s. when she gets to Amsterdam, then in the 90s when she gets these letters, and then now when there's a film made, like a VR piece made about her. So that's her line. And then there's like the author, the maker's line, like what's the question of... that you want to know, that you want to know what happened, like in your own confrontation with, like what you said, you kind of go into this like true, like whodunit kind of thing, knowing that then there will be an answer. So what do you do? So that's, as a character in the piece, that's my development. And then it was really like a long process to weave these three together, that then it becomes, you get something at every point, you get something on all these three levels. And then we found the scenes that belong to these emotional levels, basically. So, yeah, I think to conclude that it was not so much as how do we make a story of what's not there, but how knowing what all is there, how can we get the story as it often goes with documentary, I think. And that's why it also requires it required years to do that. Also because to understand, we needed to understand this story in a way, like on a deeper level. Also, like having a child in between, you know, like in the process. Yeah, first I identified with Sonja and the child. So what happened to her? So I was not so much focused on the parent. And then suddenly, you know, you just feel more in line with the experience of the parents. So it changes the story. So, yeah, I don't know if there was a definitive, like, do we have enough? But it just came more and more together, more together. Yeah. Yeah, I think you wrote...

[00:20:12.597] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: eight different versions of the script. First a very long one with all the necessary information you would traditionally want with a documentary. And then, of course, then you start trying it in a VR, you're like, oh, this is way too much information. Like people can just not listen to this while they're watching and walking. And then I think the last line, or not the last, but a very important line is that the visitor will have their own imagination as well. And I think that's where we went through the rabbit hole. We're like, oh, you know, we want to give people a comfortable space to make connections themselves as well. Make it their own. Activate their own. What if?

[00:21:01.066] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah.

[00:21:02.547] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah, it's kind of I think actually, Marty, at some point you created an extra research question, which is how could you trigger imagination someone's imagination in their head in VR while you're showing imagination. It's unanswerable. And I think I wouldn't claim we have fully answered it, but what we did see at Cannes which we didn't want to assume is that the story is particular enough and specific enough, but it has a very strong universal push that you understand whatever Sonja lived through, you also will have a grandma, a granddad, a mother, a father that might have a piece of history that you don't know or not fully knows. And the only key to that is a question or a simple one. And I think everyone, who visited at Cannes was very generous and lovingly sharing that connection. But I think when we started making or kind of listening to all these possible angles in the recordings, we absolutely had not decided our end. So the ending of Lacuna, I think, literally came last in the last four or five months of production.

[00:22:19.756] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah, it always said epilogue. There was a chapter epilogue, and then here will be the epilogue, but we never knew. Okay, what is it going to be? So we knew that there had to be some reflection, but yeah. I don't know if there's an answer to your question.

[00:22:35.563] Kent Bye: Yeah. Yeah. So that's all really helpful. And one of the things that, as I was listening to you, a follow-up question that I have is that in the film at the end, it says that Sonia never read these letters from her parents, but yet it sounds like that you did have access to those letters and was reading those letters. Did that help to flush out the arc and the story and Because the main narrative is coming from Sonia and her memories, but they're very fragmented. And so were you able to fill in a lot of the other gaps around what the story was by having access to these letters and being able to read them and be able to tell parts of the story that maybe Sonia didn't even have direct access to?

[00:23:14.703] Maartje Wegdam: Well, I think just to clarify, Sonja did read the letters. Her sister never read them. So Sonja read them once in the 90s and then never again. And then she let me read them. And then I read some of it to her. So you hear me reading out the letters, I'm reading them to her. So that's kind of a co-reading session, kind of, which also it was for me a way to see whether there would maybe new memories would emerge or to see if that would trigger new conversations. But you're right, it was also to... Because if you strictly go from Sonja's memory, there is not a lot. So there is not enough to tell the story from. So you need these other information pieces, like also the photo books, the photo albums, that give you visual impressions of what they look like, or that they were loving parents, the way they hold their children. So you get other kinds of information from these visual imagery. What struck me in the letters, which is interesting, I would have expected this year that I wasn't able to read them, that there would be a diary, like the war was from 1936 till 1943, they were writing letters. So I was kind of in my head thinking like, oh my God, you know, the war is approaching and it becomes more dangerous and there's always these anti-Jewish measurements. So how will they reflect on them in the letters? What's their political point of view? What are their... The pros and cons of going into hiding, for instance, you know, they're a train of thought. But then I got a chance to read the letters and it was really like 95% was about the kids, like what they ate. And you know what they said, they said Nana and Dada and they were walking. And so there was, you could only tell from the dates. And sometimes there was a little sentence that would refer to something in the war, but not like super explicit, only like two paragraphs or so. And they are in the VR. where they express themselves so to me that really struck me like oh wow and then i was like did they not think about did they not see it coming but then later on i felt like and also with these what i realize now also when you know there's so much like news like about conflict and war around you like it's also a mechanic to zoom in on what's really important to you right now and to like on you know the small family and things that are like directly around you and that give you a lot of love and optimism. So I think that I assume that that's kind of what happened. So, but it didn't give a lot of information as to what happened when, but I could make a timeline from like general research on like Amsterdam in the second world war or the Netherlands and what happened when, and then put their letters next to them. So knowing that the war broke, when they were in Amsterdam and when it was her birthday. So that you see in the Amsterdam scene, it's like you see a birthday scene and then the war breaking that is actually based on information. So everything that's there is based on these timelines. It's not a fantasy of ours. also the way the apartment looks is from the floor plan of the apartment we didn't invent a whole apartment so we really try to to use what is there the way it's there and then to kind of allow for different versions like for instance in the apartment of reality so there is the floor plan but there's maybe you can still imagine different ways of filling up that space and eventually we present you one but then you know like this is only one version So then it allows for your own imagination, I guess. So that's how we played with facts and assumptions, basically, or imaginations.

[00:27:03.513] Kent Bye: Nice. Yeah. And part of the experience of watching this piece was that you're doing a lot of things to replicate fragmented memories and haziness. And so I had this interesting experience where the experience of the piece kind of mimicked the way that the story was told, which was that I was sometimes having trouble dropping in and kind of understanding the context where the story was. And then, you know, eventually I kind of latched on to specific moments once the actual spatial context started to become more clear into these scenes. Then it started to crystallize more. And then I found myself, I went back and watched the beginning again. I was like, what was happening in there at the beginning? And then I was able to see like, oh, okay, well, this is like foreshadowing other parts of the memories that are being revealed. But that even then it's like these little glimmers that you don't, quite get a full spatial realization of it. So you're kind of like in this void space and you maybe have the cracks of the void space be opened up. And there's a dual mechanic there of head rotation. So as I turn my head, there's a head locked shaders that are morphing around, but then there's also the ability for me to walk around a space that didn't have as much impact on the world, but things were being revealed. And it was hard for me to know whether or not it was just being revealed or if I was moving into a new spatial context and that was revealing it. And so there was a part of the experience where I'm also trying to figure out the mechanics of everything of like making sure that I'm like discovering or seeing things and being unsure as to like how much agency is there in terms of, I need to do this to be able to reveal that. So the way that the story is being told, I think is also replicating this kind of like exile, being lost in a void space, in a liminal space, trying to grasp onto some memories that aren't quite crystallized yet. And so, yeah, I think by the end, I think the stories settle in. But in that beginning, I found myself a little wavering. After I'd saw it the second time, that experience was only from the first time me experiencing it. So as creators, I imagine that it's difficult for you to know for sure because you already actually know the full arc. And so it's hard to have that beginner's mind as to like how people are going to be parsing that. But just curious to hear that development of this form within the VR medium to sort of replicate this fragmentary nature of the memories and how the VR medium was able to really amplify that way more than any other medium.

[00:29:28.263] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Oh, it has been a very interesting journey. I think we have left, in our Unity work project, I think there are another 43 interactive tiny experiments not used. We had one really big darling we had to let go of. I wouldn't say kill because it's not completely killed, but I'm dying to tell this anecdote because the floaty, wavering, kind of almost wavy quality that you describe came from an idea, a very, let's say, our first conceptual moment in this production. We thought, what if... if you go through these memories of Sonja and they exist in multiple forms, so that the audio we always put down as a linear experience, so the audio would always be guiding, but then the visuals and the space would be a little bit almost untrustworthy. So depending on where you go stand, you might see a slightly different version or different color, different design. And, um, To get that interaction going, we thought maybe perhaps, you know, there's a portal that you can step into. Because I think we always wanted to work with an emptiness and a completely filled up scene. And to go between them, we thought maybe an interactive portal would be the way to go. So Harm, Harm van de Ven, who worked with us very closely, he developed and art directed this piece, has spent many, many hours making a beautiful portal. Creating a really cool portal. Very cool portal. It works like a dream. It looks like a dream. We have it in many variations in constellations, like what would it be if you have four or five portals at the same time? And it was an absolute pleasure to go through all these iterations. And now we're in this conversation. I remember while we were working on Lacuna, this whole process of figuring out portals and design, Margie, do you remember these pictures started to come in from the black hole they photographed for the first time? So when Harm had a portal done, I don't know, two weeks later, I saw news on a big news site like, oh, you know, they have figured out to reprocess certain data to get a picture of a black hole, but it looked exactly like our portal. And I think it was a very orangey kind of donut-like picture that you must remember it, Kent, like it was quite big world news. So we had a good laugh, like, oh, we're kind of making memory portals and science is going to go like, oh, let's just make a black hole memory portal. So that kind of just, I don't know, very serendipitously happened in our, um, parallel to our process. So we, um, we had a portal and then we started testing it last summer, 2024. Am I right? Yeah. 2024. So we had the narration laid down in a beautiful soundscape and mix from Rick Newdorp, but we tested it with colleagues who are quite experienced with interactive formats and they were very honest and gentle with us to explain that it gets a bit in the way. So this portaling between emptiness and between these very detailed scenes was also quite distracting. We really loved our beautiful portal, but then we kind of, because we didn't want to throw away the fact that there needs to be some kind of transition between emptiness and a lived scene. So we had a bit of a cry, figured out that the interaction is not working. I particularly did not have a good time at that moment. But Harm, yeah, is such a wizard. Like this portal is actually an element you can move around. So if you walk towards the portal, it can actually float away. And he kind of discovered that if you make it non-interactable but dynamic, so it kind of moves in the space and it, you know, it... Follows your gaze, basically. It leaves kind of a color shade or you can... So then at some point, the whole portal... Imagine a ring just got away, but then the color blobs just stayed. And then we use that to trick your gaze into opening up a second 3d scene. So this whole portal kind of morphed into some kind of quantum physics, ulterior dimension that was way bigger than, you know, a classic circle you could step into. But then I think at some point we really embraced the narration and kind of dared to let go of, I really wanted for people to kind of feel seamless. Therefore we needed to let go of the interaction, but I think by giving your gaze some agency in where you want to pull open the scene. That's how we, yeah, we actually discovered a new memory language, just to call it that. And then we started playing around with color and these shaders. And with this process going on in the summer of 2024, we also already invited three different visual designers to give a very specific look to the different moments, the Surinam moment, the Amsterdam moment, the Apeldoorn moment and the ending, because we figured out we didn't want to communicate dates all the time to tell you like, oh, now it's 1939. we kind of wanted to make you feel intuitively comfortable, like, oh, we're in a different moment now, and I'm not sure when, but it's clearly another moment. So we kind of picked these three visual designers to let them completely free and create these very standout scenes. So the emptiness and the scenes kind of, you know, they can work with that floaty, non-portally design.

[00:35:44.761] Kent Bye: Yeah. And the other thing that I noticed while watching this piece was that when it did get more crystallized into a spatial context, we're taking it into a number of these different locations, like a home, like a hospital context, when the soldiers are coming in and you're kind of like surrounded by these car lights at night and then on a ship and then, you know, into this new home in Suriname and meeting with her aunt that becomes her mother. And so it's, you have these spatial contexts. And I was really struck by like one of the scenes that you start describing what we're seeing in a way that it felt like this kind of blend of like, oh, this is how like you would tell the story in literature. You would be describing something, but we're also seeing it. And so, but sometimes we're not always, you know, in films, we're not always like explicating the location because we can see it and you just need to show it. You don't need to describe it. And so there's this interesting blend between giving these descriptions and then showing it, then also us allowing the viewer to be within the context of these spaces. And so context is a big theme in terms of being able to tell a story by taking people into the spatial context of the scene. And so you have from home into this kind of exile, into this long distance journey, into this new home through the spatial context. And so I'm just curious to hear some reflections and elaborations on developing these scenes that also have overlaid on top of them many times the photos. And so you have the archival photos that are also adding like more historical context and then the recreations of these scenes later. either faming photos or photos of the spatial context that then you're fleshing out. But love to hear you kind of reflect on the way that in VR, the place is so important that you really need to kind of ground people in these locations and then find ways to then anchor the narrative and the story on that through both the photos and the narration that is telling the through line. But yeah, just love to hear some reflections on that.

[00:37:48.075] Maartje Wegdam: Maybe it would be good to explain how we developed a few different scenes, because I think it's a bit difficult to generalize here, because what we were saying earlier, the different modes of memories and how that works, we took those ideas to create different scenes. So for instance, what you started with, the scene where you actually say you hear something and then it's actually being shown, Those are like four moments that are actual memories of Sonja. So she's only saying what she sees and what she feels, the rain on her skin, for instance, if that is an actual memory. So what I did in the conversations with her, she told me, I have four fragments, I have four snippets. That's it. And so with these, we took time to really do imaginations with these four snippets, like over and over again. So like we did like every snippet, we did it five or ten times. For instance, the boat scene, because you referred to it. She says like, I'm standing. So she just recalls it like I'm standing on a railing. I don't see the boat. I don't see anything. I don't know if my sister's there. So and then we felt from this audio And it's interesting because it is contradicting to what you would say in a movie. It would be like, see a cow, say a cow. But it is the whole point to show what is there, also to show what is not there. So if you only see two windows and you know that there's a boat, but you don't see the boat. So by showing those two windows, You don't show the boats, basically. So it is also a way of not showing something. But we wanted to, with those scenes, really focus in on and also kind of disorient you and put the audience in the child's perspective. I mean, you're showing not only the boundaries of a boat, but you're showing it from a child's perspective. So you also get the feeling like, oh, I'm in her imagination. So it's not just to show the... a sense of where you are, but to show a sense of how she must feel those things. So it's a way of getting into her kind of mental space more than the actual space, recreating the actual space. And that's why it also has this like Rizzo kind of style, colored, abstract colors, because it's something like intangible. And in these scenes, there is no archival materials. There's no photos in these kind of scenes. There's just like what she's recalling, and that's what you see. But then there is also, for instance, the scene... to contradict this is the Apeldoornsebos, the hospital, the psychiatric ward. There she doesn't have any memories of it. The only thing that she says is that she maybe, when the napkin rings have been buried, maybe she was there, but she says it's not a memory. It's just that I think it's maybe... Speculation. Yeah, it's a speculation. So then it is more a type of told memories or like communicated memories that also for her give her a way to kind of make sense of what it was like and also for us so you have the letters there so that the in those scenes the letters i guess are the instead of her memory the letters are the chain plus the narrator's questions And I think there we wanted to show you, we wanted you to give a feeling of this actual place, this psychiatric ward, because it's an amazing space in itself. We thought we cannot just pass by that. It's incredible that in the middle of the war, there was this space where 1200 Jewish people were living out in the open, not in hiding even. in the Netherlands where, you know, in Amsterdam, the Radzias were already, you know, like weekly repetitive thing. So like deportations were happening. And this was like this kind of heavenly space where people felt free to play sports or go to cabaret we know from the letters so we felt we need to kind of honor that space and use what is there and recreate more also because there are a lot of pictures and there's a lot of archival footage so in Sonja's memory although it's not her own memory but in her mind she has a picture in her mind of what it's like So we want to kind of ground you more in that sense of space of place. So it's a different kind of place.

[00:42:26.524] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah, and I think just a tiny addition that one let's say, borrowed memory she has is about a very tiny picture of herself on the path in front of the house they lived at that moment in Apeldoorn. And she's describing it to you. Maybe you remember this moment where you see a dark house and then this photograph appears. But her memory is not exactly correct with the picture you see in front. But the picture itself is also quite blurry. And Yeah, we kind of wanted to bring these two together, not to see the faults in our memory, but that, you know, transferring a lived life to a photograph, to a memory. And then a witness looking at it, that like it has four layers of existing. You watching it, the photograph, Sonja's narration, and then the original event. Of course, these are intentions we have as makers, and it's great if you catch that at that moment. But it's also, I think, through all these variations in these scenes, we want to make people really feel big history collides, kind of exists because we have personal history. We have these tiny moments that are a little bit imprecise, maybe incomplete, but, you know, they build up to something big.

[00:43:46.124] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah.

[00:43:48.268] Kent Bye: Yeah, I wanted to speak a little bit about my peak emotional moments and the experience where there's the anticipation and fear when looking outside the windows inside an apartment, I see these huge soldiers walking by. And then there's another scene with the soldiers that are not occluded or much. They're still like a scale differential where they're really big. But then there's the moment when... All these 1,200 Jews are hiding out in this psychiatric ward institution thinking that that would help protect them, but yet it gets raided and it's like in the night. And so you have these Jeeps or cars with spotlights that are creating this real interesting void space where you sense the tension of the raid and also the parents being taken away and the children having to be left behind. Yeah. And then there's this exile moment where they're traveling to a whole other country and meeting up with her aunt. And at the end, you know, there's back into the void space and the music kicks up to really draw the emotions, talking around the fates of her parents who died in the Holocaust in Auschwitz and Germany. the dates of their death. And yeah, I think just the way that it ends just to bring up the emotions of the whole experience. And so, yeah, as you were telling the story, there's these different spatial contexts, but there's also like the building and releasing of these emotional peak experiences and trying to really drive the emotional arc of the story. I'd just love to hear any reflections of, like you said, there's like at least 20 different versions of the script and lots of different ways to sharing this information, but it seems like the core heart of the story is approaching these different turning points and these peak emotional experiences. So I'd love to hear any reflections on the process of cultivating that contrast to build up to these peak moments.

[00:45:45.049] Maartje Wegdam: Hmm. Good question. Yeah, I guess that kind of refers back to, I think what we started with these different characters who all have their emotional arc and they all need to come together, including the visitor. So there's like four. So in like relatively short time, that's like half an hour, you have like basically four emotional peaks that need to, like, this is from the creator's perspective. So, and I guess they cannot be all at the same time. So the way it is structured is that in the middle of the experience, that's a little bit after the middle, I guess, that's the psychiatric ward. So her parents give away their children. So that is, I think in a sense, it is the void that it all turns around. So in a sense, that is the moment that this whole story kind of starts from. Otherwise, we wouldn't have made this story if that hadn't happened. So I guess that's kind of the black hole that kind of consumes everything. And that, of course, collides with the parents' really intensely emotional moment, which is the decision to give birth to children. And I think, I mean... In reality, when they were separated, they went to concentration camp Westerbork. And from there, they wrote letters on how they missed their children, or kind of in hidden language. And in the end, they were deported to Auschwitz, and they got killed. So I mean, if you continue the story, that line actually goes further. But we chose to stop their storyline there, because it is Sonja's perspective. And it is about this decision. So this decision is their key. So that is the key question of the piece. Like one of the, I think, maybe two or three key questions is like, how do you decide something like that? For the parent storyline, that's their key question. So since their storyline ends there, this is the key moment. And also because in the middle of a piece like this, you want to have some kind of raising the stakes kind of moment that you feel something's at stake. It was not just, that this family spent war together. No, they actually decided to hand them over to strangers. So it's like for you as a visitor to kind of realize like the depth of the story more. So that's, I think, why it kind of hits at that moment. And then earlier on, I think you have setting this up is like you get through this emotional moment because we set up the life of two young people, Sonja's parents, two just regular young people starting out to build a new life and having children and just having hopes for the future. So we, I think we, because we portrayed them in a really It could have been the neighbors. It could have been you, like, in that sense. And to portray their lives and their perspectives that they had, then that scene really contradicts, like, and the soldiers really break that hope and break that perspective for them. So I think that's also a turning point that was really deliberately chosen. Yeah, to kind of emphasize... That they were not Jews. I mean, they were Jewish, but they became Jewish during the war. They became the exception during the war. So they were just people, basically. So to set up that turning point, that connects with the turning point of them having to decide to take care of their children. And I think Sonja, earlier on, in the beginning already, says, like, I don't know how I feel towards my parents. Like, even in the introduction, you hear... me asking, so how do you feel about your parents? I don't know. And then she comes back to it in the middle, saying, like, I know that they love me, but I don't have feelings for them. And then you know that already when the scene of them deciding to hand over their children. So you know that that decision will not only rob them from their children, but also from their memory of them. So it becomes kind of intertwined. And then eventually you have Sonja saying that there's the layer of this questioning and knowing that you want to know more, but not having asked, where you have different moments in the piece that point to, like, I didn't ask then, I didn't ask then, I still didn't ask then, and now I didn't say I'm here and I still didn't ask and I cannot ask. So I think that ending, if she would have said that in the beginning, it would not have this emotional load. But that's because you have all this background of these former peaks that then it hits. And I must say, it's true what Nienke says. It's like in these 20 versions, I think every scene has been in every place. So it was kind of, I knew, it's like knowing what kind of arc you're looking for, but what scene would fit to, there had been additional scenes, of course, like what scene can have this function? Like there was other scenes with other artifacts that she received back and we had like whole ideas to how to tell that. And then it just, if it doesn't have a function like that in the story, then it's a nice scene in itself, but it's cluttering. So then it needs to just go out. So yeah, that's how we molded it in the end.

[00:51:11.666] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: So I think this is exactly the, let's say the, how would you say it in English? Like the skeleton of the piece. So I think deciding on these arcs, but as you pointed out, Kent, your emotional buildup, what I proposed in tandem to Marge's considerations for the script, we give you quite a bit of darkness at the beginning, the emptiness, the lacuna. And it's actually the effects on your gaze and your watching becomes very mildly more intense. It grows with the intensity of what Sonja is trying to express. So I think especially the scene where she's like, yeah, I know my parents loved me, but I'm not sure what I felt for them. The effects become a bit more outspoken. So in the design also, we tried to make this more gradual rising line. And I think the scene where a lot of the memories start turning around you, we kind of make a little flip there Because we take your agency as a visitor and the scene is spiraling around you and you get a little bit, well, maybe a lot disoriented or at least through the buildup of the music, you get into a rhythm and then we release you into the sea, like her final journey to Suriname. But I propose that quite quickly to the team, because I find it quite important. You feel a contrast in how the space absorbs you as pitch you out and kind of lets you breathe or kind of takes your own concentration. So they kind of collaborate with these moments with Marcia points out, but yeah. I really love music. So I kind of, because we mix the audio, the whole audio mix first. That was really the whole VR is built in audio first, then interaction and last visuals. So the whatever tension or let's say, yeah, tension arc, is that the word you would feel would already have to happen through audio and then through image, not the other way around.

[00:53:16.392] Kent Bye: Hmm.

[00:53:17.403] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah, and we also refrained from trying to give too much on all levels. For instance, this moment of these three trucks that became the end visual, but already in the audio, And in the music, I mean, it is an emotional peak, but you see in all the sounds, visuals, interaction, it goes down. So there's almost nothing left, basically. So instead of using like all the information, because there's a lot of information on when that happens, you know, this raid or, you know, there's... You can fill it up with all the things you think and you can actually show the raid. You can use the sound of trucks and of... I mean, but we were also thinking like... What sound will do justice to this event? I mean, what kind of things to describe will do justice to what happened there? It's like, and because it's not so much about what actually happened, but what the impact was on Sonja and on her parents, I think. it was really important to stay away from too much music and stay away from like all these visuals. But then after then what Nienke said, there's this like it almost feels like a pause and then it's kind of like a almost like a roller coaster that just goes over the edge. Then you're being released into this well, it is also connected to the theme of the flight, but it's also meaning, I mean, your body also needs to get out of that situation. So it's also a way of giving you a little bit of breathing space and just being able to be, you know, struck by the imageries and the sounds and kind of let be taken elsewhere. So yeah, it's always, I guess, double meaning, both from the content and for what you need as a visitor at that moment.

[00:55:08.749] Kent Bye: Yeah, just a follow on to the four storylines and the arcs, because you had mentioned that you are in some ways creating yourself as the creators of this piece as one of those four arcs. And when I was watching it, I was seeing the way that your journey is trying to pierce the veil of what the story actually is. And you keep coming back to kind of unpack it. But as I'm watching the story, I'm also kind of more focused on Sonya and I'm not necessarily tracking what that narrative arc of the creators are. So was there an emotional peak for the storyline of the creators? And then how does that story get wrapped up if that is indeed one of the four storylines?

[00:55:45.885] Maartje Wegdam: I would say it is one of those four storylines, but it is very subtle because, frankly, it's not about us. It's about, you're right, it's about Sonja and it's about her story. And it's not about, oh, my God, you know, now I found that piece. Like, what am I? So we felt like it was a struggle because it's like I didn't want to be in it, first of all.

[00:56:05.270] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: That has been quite a bit of a discussion because I have been convincing Marcia, I think, for the first year she needed to be in it. It's like, no, no, no, no. And I'm not sure if this did it, but I showed her a documentary I really admire. It's Stories We Tell from Sarah Polley. I'm not sure if I have the title right, which is a completely different construct, but I find it so beautiful that she's the narrator, but also her stepdad narrates bits about her, about her mom, and then they act out whole scenes. Anyway, it was a bit... That documentary was very hybrid in the sense, where do you place yourself as the creator, the narrator?

[00:56:46.664] Maartje Wegdam: But I have to say... I have to say, but that's not really the reason. Well, that's, yeah, it's a different description. But I mean, because she, it's her story. It's about her family. It's about her dad. So it's very logical that she would be in there. But this story to me felt like... Apart from the fact that I'm more comfortable behind the camera and as a creator than, you know, but I always said, like, if it's necessary, I will do it. But... For a long time, I just was not sure that it was necessary. I just didn't want to overstep. That was it. I just didn't want to step into the scene and then make it about me or my search for what? For truth or for... So I always felt it had to be about Sonja and her parents. But then when I think it's quite in a late stage when we found that as a bridge to the audience... Not for giving information, but asking the questions that you as an audience might have or to kind of infuse the questions in you so that you will ask them. Because otherwise you leave a lot of thinking space to the audience and it's already quite confusing. So to kind of have a lifeline. Like some guidance, I guess. That was a role that then I got comfortable with. Like in this way, I could actually see myself, not as a character, basically, in the space. So then the emotional or the story arc is not in such a... way emotional that it has this big peak but it does develop in the sense of setting out to kind of a whodunit kind of story and then realizing like oh you know what was I thinking like more like being confronted with what was I thinking that I would get out of this and how like maybe even being surprised that someone doesn't know where I think the emotional peak comes at the end when Sonja points at me and says, so what did you ask your parents about your past? And then also like in reality, but also in the piece, I feel like I'm tearing up. Like you're so right. You know, I'm asking you, who am I to ask you all these questions and be surprised about you not knowing anything and then coming to terms with that. And then, oh yeah, it's a piece about not knowing about your Holocaust, you know, youth. And then, but who, I didn't, you know, I'm now busy with you and not with my own parents who are in their seventies, you know? So I think that there is an emotional peak, but it's just really subtle. And we made it in such a sense, what Nienke also says, that in this piece, it becomes the question to the visitor. So it is not so much about what I... You don't hear my answer also. So it's Sonja asking me, but she's really asking you, like the person. So it's allowing you there to have your own emotional... peak and be like, oh yeah, a realization, like what should I, is this something that... Yeah, I do remember the moment when that happened, if I can reflect on that.

[00:59:55.059] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: There were versions of the script where we were struggling, we were finding a way to find an introduction into the experience and introduction into the story. I'm glad that bit where you hear Sonja and Marce kind of decide, okay, shall we start? Yes, yes, let's start. Okay, you're not filming? No, we're not filming. You know, it kind of lays bare how this has been made. I think that's a strength, but it was a bit of, you were not immediately convinced, Marce, that that could be in there. And we fiddled around with all types of introduction where you introduce yourself and kind of explain why you started interviewing Sonja. But it became very tried, how do you say, very like... Yeah, intellectual.

[01:00:36.342] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah, yeah.

[01:00:37.122] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah, very intellectual. So we still had no ending. We still had not a good beginning. And I think you proposed like, okay, I'm just gonna... Do a complete overall of the script. Is that okay? I'm like, yes, go for it. And then you came up with the forecasting. Like, what if you just think about a user, a visitor's perspective, you get into a VR that's going to be semi-metaphysical. Maybe it's nice to have a bit of a metaphysical beginning and you kind of pulled the rainy scene to the beginning, which already makes you curious. And you're like, oh, okay. You know, what's this woman going through? And then you just skip the whole introduction part, but you just use it as an induction, kind of almost like a hypnotic moment to get into it, to be comfortable in the scene. And then suddenly it was all solved. Not on a level of information, but more on a level of how the immersion makes you ready. And that gave a lot of freedom to put certain facts a little bit further away in the script. So we didn't have to push a lot of information.

[01:01:44.212] Maartje Wegdam: Hold you with your information. Yeah, kind of.

[01:01:48.417] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: shower you with facts. And then Martje very beautifully kind of put little breadcrumbs in different scenes so you could process it a bit more lightly. But that was, I think, the breakthrough. But that's also when we found our ending at some point.

[01:02:06.776] Kent Bye: Yeah. Yeah. And I have to say, just by watching this piece right now in this moment and what's happening in the United States, it starts to land a little bit differently in terms of these historical docs that I've been watching for many years now, but it just feels a little bit different when the global context seems to be inching back towards this not following due process and authoritarianism and these behaviors that have happened in the past. I just really appreciate being able to hear these stories of the impact of that and as I was watching it and also thinking about how this is a story that's still going on today. So yeah, I don't know if you had any thoughts on that.

[01:02:45.953] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah, it's curious always like when you're working on a project like for this amount of time, like how the context changes during the making process, but also afterwards. And still also, I think as the creators, we have to relate to the story again and again and in a different way. So still it unveils the same depth to us, you know, so it's still unveiling itself. it doesn't stop when it's finished when the piece is finished it doesn't stop unveiling itself and i think that's the beauty of it and in this story also kind of um yeah uncanny or kind of it doesn't make me comfortable let's let's let's uh yeah yeah i think um

[01:03:36.437] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: In 2022, I think we met when the full-scale invasion in Ukraine happened. And from 22 to 24, I think, of course, the situation in Afghanistan escalated. Marge and I had quite a few conversations about also all the children that are going through the same process as Sonia did, saying goodbye to parents or maybe saying goodbye to their country for forever, or maybe for a long time. So I think the universal message or kind of the universal angle of Sonja's experience, unfortunately, is continuing in many ways in the world because this project really starts and continues with, you know, the questions lost, the answers never given. Yeah, we find it very important that it's not just only a piece that was motivated from a Second World War historical interest. It started with an interest for someone going through a big loss. We cannot introduce Lacuna without explaining the context, of course, but I think Sonja can easily talk to someone who is six years old now anywhere in the world. And that, I think, like Marty said, it makes me very uncomfortable. Naively, maybe at the beginning of 2022, 23, I hoped, you know, this is a particular last type of piece about a witness of the Second World War, but it became so much more. And we're only beginning the tour this year with Lacuna, so we will still need to figure out how to present this in other contexts, in other places. We haven't had other kind of conversations yet with curators. I think people are still interested in, let's say, the cross-section of history and today. But yeah, we're also kind of aware that that can change or people can maybe start making other curation ideas. But for now, I think that the current situation everywhere and the historical relevance, they collapsed. They're now the same, unfortunately.

[01:05:47.089] Maartje Wegdam: I think what, yeah, to add a tiny note is that, like what you say, it is about witnessing, but it's, I think, even more about impact and experience like this in your early youth, like what the impact of that is. 80 years later. So, I mean, just count, you know, in 80 years from now, we will have just the same impact. So I think it's also about that. It's not only about witnessing what is happening now, but the actual personal impact on people and generations and like, that it's just such like an impact that like every rocket that is like hitting now is like, having impact in eight years so it's just not only now that it's happening and i think that's what its story i think it's something that it does is just shifting away from the current affairs and by looking at the past in this sense but it's also kind of looking at the future in another sense yeah yeah and so i guess as we start to wrap up i'd love to hear what each of you think what the ultimate potential of immersive storytelling might be and what it might be able to enable The ultimate potential. This is not a final answer, but I think what an immersive experience can do is Physically, with your body, not only with your mind or emotions, like a lot of experiences happen here, but I think with your body, it can take you somewhere. It can take you into someone's mind, into a space in the past. So it makes your body feel like you've been somewhere instead of that you watch something. And like through all these means as like giving agency or like whatever, how many degrees of freedom you can have, I mean, that can all evolve. But I think the whole fact that you can bring a person into a space, like you step into an airplane and you go somewhere to experience the world, you can do that. Can allow for, I wouldn't say empathy, but empathy. to go along with the either narrative or world or a character that is presented to you and to identify maybe with them. Or I just think it's a really strong, in the end, for me, a really strong like emotional tool that you can generate that or you can allow yourself to have these emotions because you're there with your whole body, I think. And that's something to me, I think, unique to immersive storytelling or immersive experiences.

[01:08:42.822] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yes. I'm trying to think of something that can add to this because this is something I strongly believe as well. But I think when I explain what I do to someone at Cannes who really makes film, I truly believe that integrating let's say your agency in space and time is a very powerful form of artistic expression, but also a very important element to your life that we often only, I'm not sure if unconscious is the word, but kind of not pay attention to, like we maybe take it for granted. So kind of integrating your space-time presence In my case, I really like narrative experiences and how they can kind of guide you into, you know, reflect on that or kind of discover a new way of being even, or a new way of experiencing. But to put it simply, I enjoy film a lot, but I think the ultimate potential of immersive experiences is that you will just like a very nice meditation or like a, a beautiful dinner, I think you have integrated your senses and your being here right now in such a way that you can walk away with something that lasts a lot longer than something you watched. I think Martje put it very well. And I think VR is just one medium for me, but I think this can also happen If I look at the other pieces at Cannes, they play around with AI also as a catalyst to have other types of conversations or other type of opera. The winner at Cannes, our colleagues, Dutch colleagues. I think you need to kind of touch on something in yourself. And I think the immersive art really helps you access that more particularly. Hmm.

[01:10:40.057] Maartje Wegdam: so not to say I don't think we want to say that every experience should be an immersive experience and I also you could argue for film being immersive to some point but like just let's stay away from that discussion I do like the discussion because for me film is very immersive but people forget to describe the chairs and the space and the darkness and the beard holding in your hand because that's part of it yeah for sure yeah

[01:11:07.679] Kent Bye: Nice. And is there anything else that's left unsaid that you'd like to say to the broader immersive community?

[01:11:16.268] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah, let's make more independent tools. Let's go for something really radical and make open source radical tools that are not going to be hijacked because I really want to say this because I think every time I go to a big festival, there is some weird meta update and everybody has to rebuild their project. It's so unsustainable and it's so unbelievable, unfriendly, not user-friendly by such a big company. There are a million of other arguments not to support meta too much, but this is becoming ridiculous. These tools are so unreliable. And we're laughing it off, but it's, it is not okay. Like we really need to make more like Blender style open source. Yeah. Our own tools. And I know it's not an easy thing to do and it's easily said maybe, but come on, you know, we're at Cannes and three, four projects are almost broken before the press comes in. Yeah. It's extreme. It's ridiculous.

[01:12:26.755] Kent Bye: Wow, so there was an update that got pushed that broke two or three experiences?

[01:12:31.399] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah, I think a week-ish before the festival started. It's something that relates to PC VR connections and anchoring, and we're not entirely sure what they updated because their documentation is so, yeah, not transparent. But in our case, I think we fixed it by updating both the software on the PC and the headset and kind of aligning it, rebuilding the whole build to get the right software number on both systems. So the fix was not that complicated. But before you have figured that out, I think our colleague Cameron from In the Current of Being, like he has been sweating it off, I think, to the very last minute before the press came in. It was, you know, I've seen this before at Venice a couple of years ago. Yeah.

[01:13:18.254] Kent Bye: Yeah. It's so unfair.

[01:13:19.696] Nienke Huitenga Broeren: Yeah.

[01:13:20.436] Kent Bye: Yeah. Well, there is Godot and maybe Valve will come through and release a headset that's built on Linux. But, you know, up to this point, yeah, we have to deal with some of these platforms that are not always mindful of the LBE context.

[01:13:33.008] Maartje Wegdam: Yeah. This is maybe not for the broader community, but it would be really kind if you would mention that we have an amazing producer here. That was actually without them, we just would not have been able to do this. So it would be just nice, like in a general sense that if you speak about this piece, just not only mention us maybe.

[01:14:00.839] Kent Bye: Awesome. Well, Marta and Nika, thanks for joining me today here on the podcast to break down Lacuna, a piece that debuted there at Cannes. And yeah, like I said, it's a piece that had a lot of confusion at first, but there's the through line of what is happening is resolved. And it's kind of like a puzzle of a narrative puzzle, as it were, as you're kind of piecing together what's happening. And yeah, there's certainly some moments that are going to stick with me in terms of these turning points and these emotional peaks and Yeah, I just thought it's a really interesting exploration of using the medium to piece together and tell the story in a way that would be difficult to really give the same sense if you're just using 2D media and it's kind of interactive components that are playing into those themes of piecing together the fragments. So yeah, just really enjoyed the piece and enjoyed having a chance to talk to both of you today to help break it all down. So thanks again for joining me here on the podcast. Thank you. Thank you. Thanks again for listening to this episode of the Voices of VR podcast. And if you enjoy the podcast, then please do spread the word, tell your friends, and consider becoming a member of the Patreon. This is a supported podcast, and so I do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring this coverage. So you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Thanks for listening.