Here’s my biographical oral history interview with Gregory Panos, 2025 Inductee into the Augmented World Expo Hall of Fame, talking about his journey from the early days of computer graphics to becoming a virtual reality evangelist and consultant, community builder via SIGGRAPH, as well as his long-time fascination with identity, volumetric capture of people, memorialization, and his ideas around a celebratory process of virtual immortalization as elaborated in his 1994 paper “Using Virtual Reality to Document Human Existence.” Thursday, June 12, 2025 at Augmented World Expo in Long Beach, CA. See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR Podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR Podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So continuing my series of looking at AWE past and present, today's interview is with Gregory Peter Panos. In this conversation, we start to dig into the early history of computer graphics and his journey into marketing and sales, but also generally moving into the role of community builder in the context of SIGGRAPH, but also starting to become an evangelist for virtual reality technologies and kind of build his own devices and show a number of people their first VR experiences. He's also a writer of the Virtual Reality Sourcebook, and also he is really into this idea of identity and capturing your identity through these different tools of volumetric capture, but also in this context of expressing your identity and memorializing your identity and telling the story of your life through these immersive technologies. And so he wrote a paper in 1994 called Using Virtual Reality to Document Human Existence. And so in that he talks around this process of virtual immortalization and how as you're getting scanned, he wanted to treat it as like this sacred moment where it's like you're going into a spa and it's really a celebration of like capturing your identity and your identity. expression. And so with the tools and technology, then Gregory has been capturing people's identity for a number of years. And so he kind of talks about that as well. Gregory is somebody that I've like run into a number of different times over the past decade. Probably the first time I asked him to do an interview was at SIGGRAPH. And he said, no, he wasn't ready or it for whatever reason, he didn't want to stop and do an interview or just wasn't time. But He was being inducted into the AWE Hall of Fame this year. And so I think he was ready to just kind of take a moment, step back and recount and share his journey into this space. So I just wanted to share that as a context for bearing witness and holding space for capturing these types of biographical oral history interviews. So we're covering all that and more on today's episode of the Voices of VR podcast. So this interview with Gregory happened on Thursday, June 12th, 2025 at the Augmented World Expo in Long Beach, California. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:02:25.103] Gregory Panos: So my name is Gregory Peter Panos, and I go by Gregory Panos, Greg Panos, Greg. And I started in XR in my early 20s, and I was very privileged to get a degree in communications and TV production direction in film at Ohio University School of Communications. I graduated with a Bachelor of Science, cum laude, and I moved back to New York, where I was from, in Westchester County. And from there, I was looking for work in the television industry, and I almost ended up at ABC Television. And I would have had to be a union member and then join the crew and get inducted into that whole scenario. But I read an article in Omni Magazine about Jim Blinn and the computer graphics going on at the Jet Propulsion Lab. I was so totally fascinated with the idea of computer graphics when reading that, that I went into a deep dive and I did a lot of research at the library and I found that there was a leading computer graphics lab in New York, out in Long Island, called New York Institute of Technology. And I really wanted to go there and do anything I could, sweep the floors, you name it. And I kind of gave up on the idea. I just wasn't courageous enough to approach them. But I found a computer graphics facility that was not far from where I was living in Westchester County called Magi Synthavision. And I got my nicest suit and I drove up there and I met the man that was running it, Dr. Philip Middleman, who was an expert scientist in ray tracing. Never even heard of that before. And he hired me to help do marketing. I was a very young, handsome young man. I looked good in a suit, drive a nice car. And he figured, okay, he can sell some of our services to people that want computer animation. And I worked with them for about six months and Disney gave them a contract for Tron. And there was no more services I could sell because they were completely booked up for like a year from the Disney contract. So I went down into Manhattan and did the same thing at another company called Digital Effects. And I was going to try to work in the advertising industry and bring computer graphics to advertising. And within a short period of time, they got a big contract to work on Tron from Disney, and that whole production house was saturated with that work. There really wasn't any chance to market or get any kind of commission doing that. But I hung around for a while, and I tried, and I learned a lot, and I met a lot of interesting people. And my third stab at it, I went out to New York Institute of Technology, where all the Pixar founders were working for an independent lab funded by Dr. Alexander Schur, who owned the whole campus at NYIT. He had made a lot of money on the various government grants for people that were needing education and founded the university that way. And it was kind of like the Walt Disney of computer graphics. Before even Disney knew what computer graphics was, that's what he did. And he funded this whole lab. He worked with Digital Equipment Corporation. They completely furnished the lab with electronics and equipment. He himself went out to University of Utah and he hired all the people that ended up running Pixar, Ed Catmull and Alvy Ray Smith and others that were there. And so the lab was full of scientists and artists and engineers. And I couldn't get a job in the lab right away, but I did have enough credentials academically to teach television, TB 101, in the university part of the school. It was kind of like more of a community college, really. And I wasn't really enjoying that, but I was effective as a teacher. And I tried to sneak over to the lab every chance I got. One day, someone went in there, and they made the code, and the door was left open a little bit, and I kind of snuck in behind them. And I ducked into the first office on the right, and the executive vice president was sitting at his desk who was running the lab. He was the adopted son of Dr. Schur, and his name was Bruce Laskin. He was a really super smart guy, really friendly. And I told him who I was and that I wanted to work in the field. When he found out I worked for two other computer graphics companies before I landed there, He said, do you want to work with us? I said, yeah, I would love to in any capacity. And he said that they're spinning off a commercial venture called CGL Inc, Computer Graphics Lab Inc. And they're going to start selling their paint and animation systems into the commercial market. And they need people to work with them in marketing. So I had a huge amount of marketing intelligence in the field. He hired me on the spot, and it turned out that, yeah, I got hired into NYIT in the graphics lab. I was just over the moon. And they moved me into the main office area of a beautiful mansion where Dr. Schur's office was, and I was in an adjacent room right next to him. And I had my own computer. I had a VT100 workstation. I was hooked up to their mainframe. So I built a database of competitive products and companies and services and who was doing what and who had contracts for what in the field. And I became a crystal ball. And Dr. Schur personally would talk to me all the time and ask me about the industry and build strategy for how they were going to grow their company. And they hired a couple of other marketing guys who weren't particularly that good, but I was one of their little, you know, gold nugget finds and information to help them grow all that. And I had friends in the city that worked in the art field, and some of them worked at the factory with Andy Warhol. And so in the process of running around the city and going to advertising agencies and artists and the like trying to promote computer graphics and the products that could be used to make them. I ended up becoming the primary information source for Andy and some of his people at the factory and got them completely fascinated with the idea of him making computer graphic art. But he was considered a sheep skate and he did not want to spend $150,000 for a paint system. And Dr. Schur was very old school. And he's like, you know, this man's worth millions of dollars as an artist. He can afford to buy one. We're not going to give him one. We're not going to let him come in and use it for nothing. I didn't think that was a good idea. I thought it would have been good to compliment promo stuff to just get the publicity. Years later, Andy ended up working with Amiga and Commodore, and they gave him some of those Amigas and some support. He did some computer art on it, very sort of half-assed, and it actually ended up becoming an actual art show at the Warhol Foundation once they discovered this after he had died, these 20 or 30 things he did on the Amiga. But he had an opportunity much earlier on to really get engaged in that. And when I was at NYIT, my dad passed away and he had started a business in Florida selling artificial candles and fruit and all these different sort of knickknack items to Woolworth and Kmart and importing and exporting. And we kind of had to close out the family business. He had a lot of money invested in there. And my sister and my brother and my mother, we all were living in Florida at one of our places there trying to deal with all that. So I was down there for a couple of months and there was a demo that I somehow found out about in Orlando at the Naval Equipment Training Center where they were demoing a high-speed real-time computer image generation system from a company in San Diego. So I went up for that and then I met those people and once they found out what my credentials were in computer graphics they offered me a job out in San Diego as a sales support engineer to sell their systems into aerospace and entertainment and Within a month or two. I moved to California. I've lived in California ever since and that was in Gee 1982 or 83 I left New York and

[00:10:54.402] Kent Bye: Just to also orient us in space and time, you said you were 23. What year was it when you were 23, just to get a sense of when the story started? 1956.

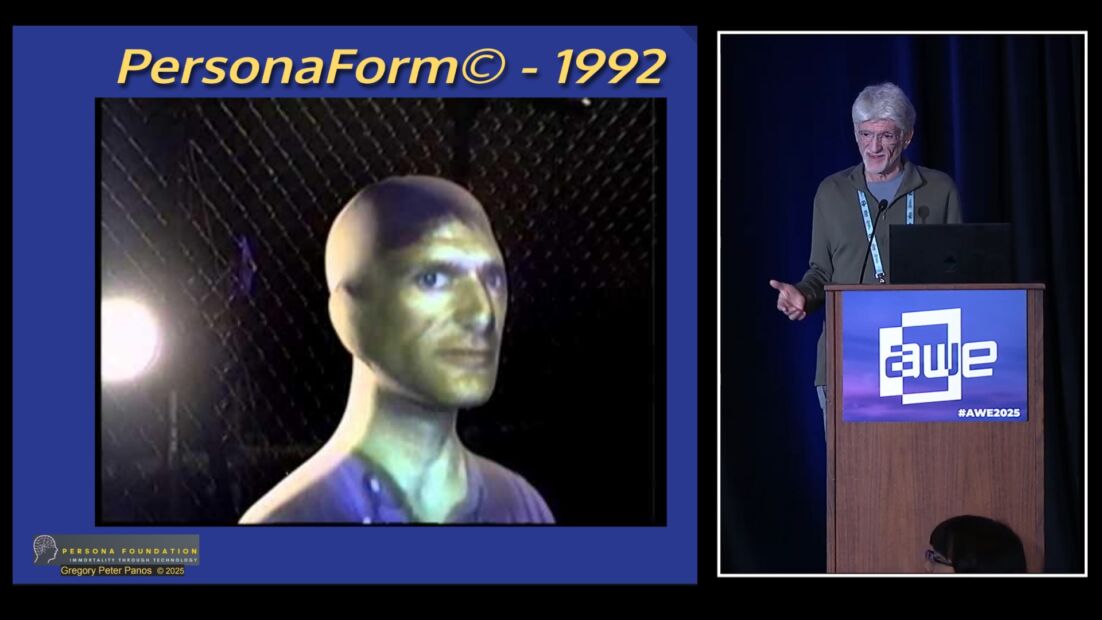

[00:11:02.447] Gregory Panos: So, 56 to 66, 76, 78 to 89, 80. And so, yeah, I worked at NYIT. I worked at Magi like around 80 and then 81 at Digital Effects in 82. at NYIT, and then I left NYIT in 82. I don't know who Steve DiPaola is, but he was also there now. He runs a huge department in a university in Toronto. And a lot of other interesting people that were there at the time went off to do fabulous things. So once I landed in San Diego in 83, I worked for them for about a year. I learned a lot about real-time image generation and modeling and model optimization for real-time, a lot of really down-in-the-weeds type stuff. And Rockwell International Corporation had started the space station division to bid on the space station contract. They bought three of our machines, one for space division, one for space station, and one for some other group. I was recruited out of that company to join Rockwell in the space station division to work with that machine and do pre-visualization work for contract support to try to win more contracts. And when I came up to Rockwell and Downey, I got a little apartment nearby and was working all the time and running that machine and hiring people that I knew to help. And then also we designed just a beautiful graphics lab with carpeting and pin beams and the machines the way they were, the fans were fine-tuned, made this beautiful cord. It was just an amazing ambient environment to come in and get computer graphics demos. So all the heads of NASA, that was like the jewel of the company to bring them into our lab and give them dog and pony shows. And I was the crack operator to like show them and fly them through models of the space stations in real time and never even seen anything like this. Even NASA hadn't adopted the technology yet. And we won a lot of contracts. And this was a time when a lot of the engineers there did not have a lot of charge numbers on their green sheet that justified their job. I ended up having a dozen of them on my green sheet. Everybody wanted computer graphics support to show what their designs were like and how to navigate through them. So I was pretty busy there, and I ended up with the computer graphics community in Los Angeles, mostly entertainment, and I became chairman of SIGGRAPH Los Angeles, which was the largest chapter in the world at the time. I was chairman twice, vice chairman twice, and that became my real communal family, the effects industry that was growing in Los Angeles. And so I worked at Rockwell until 89. They lost the space station contract to McDonnell Douglas. I moved over to the space division, which is another building, but I had more tech to play with there. But I was in a lab that was a black lab. I mean, there's clearance. You couldn't get in there without high-end clearance. So I was cleared for all that, but I couldn't give demos or bring friends in the way I used to. And then we started getting assigned to weird military projects. I got assigned to space-based laser, brilliant pebbles, kinetic kill vehicle, all Star Wars weapon programs. I just thought the physics of all that stuff, the expense, the potential for space junk, just morally made no sense to me. I didn't want to throw my youth away working in a lab sequestered away on this crazy stuff that I couldn't tell anybody about or show anyone. I just felt pigeonholed. So I left. I joined another company that had a very new computer image generation hardware system that had an office nearby. And they swore that they wanted to sell into the entertainment industry and creative endeavors. So I joined them as an application engineer. for about a year, and then they wanted me to sell to aerospace and defense, you know, help them create accounts and sell systems for them. And I write again on the same situation, like morally, I'm not interested in this stuff. And three of the other people who were pretty high up in their company had all just left for Silicon Graphics. They started the advanced system division and they were really hot to sell into the entertainment community. And I started having some health problems at the time, and I just decided not to follow everyone to Silicon Graphics, and I kind of retired at that point. I started writing and speaking at conferences about technology and computer graphics. And I discovered virtual reality and I realized how it wasn't very hard to cobble together virtual reality system on my own. And I started building virtual reality systems for private clients and myself, mostly artists and scientists. I started teaching at the Learning Annex in Los Angeles. There's an adult education. That's where I started onboarding hundreds and hundreds of people into VR for the first time. I had a close friend who taught part of the class, and I put everybody through VR.

[00:16:15.254] Kent Bye: Just a quick follow on clarification, because I know there's like General Linear and the VPL, the Visual Programming Language. So when you were putting together these VR systems, was the first VR experience something that you had created yourself, or did you try it out for someone else?

[00:16:29.308] Gregory Panos: We tried out the VPL system. I knew quite a few of the folks at VPL. One of my people I met, I got him a job there at VPL. I didn't want to go work for VPL, but like I said, I was kind of trying to stop working for other people and follow my own bliss and write and create art and the like.

[00:16:51.229] Kent Bye: So you'd seen the VPL, and then you wanted to create your own VR headset. You figured you could do it.

[00:16:56.953] Gregory Panos: More than just VPL. They were getting all the press at the time. Jaron Lanier was the Wunderkind with the dreadlocks. And I was sort of the handsome, buttoned-up, suit-and-tie dude that knew all that stuff, did a lot of that stuff. I wasn't like a philosopher the way he was or anything. But nevertheless, I was a good ambassador for the tech and the democratization of the tech. And I started speaking at a lot of conferences and putting panels together, some with Jaron and lots of other compatriots working in the field. And there was a crossover. And one of the people that I put to VR for the first time was Skip Rizzo. And he actually said something at the award the other night that I broke his VR virginity. But there were many people like that in the entertainment industry. It was the first time they had ever done VR. And I was showing an architectural simulation with pre-baked lighting, which could actually render on the hardware at the time. And it was very impressive. I had a head tracker, and I built the whole thing myself. And I can build VR systems in my sleep. And I have no technical knowledge. I didn't go to school for this stuff or computer science. But it was just joyful being around people and turning them on to this. and just seeing where their minds would go, and what they would think of doing, and I was always happy to help them. And I began to think about authoring things, and I wrote the Virtual Reality Sourcebook. And I took all the knowledge I had, and categorization, and nomenclature, and every kind of specific under-the-hood descriptions I could create, I created categories. some real pioneering categories for the field that included virtual characters and tracking systems and display technology, all different categories. There were like 100 or 150 entries in the book. It was pretty thick. It was like a consultant's Bible. I sold it for $120 a copy, and I used a friend's copy machine and hand-marketed and hand-sold these books, and I lived off of that for a while and continued updating it. Originally, I had been put under contract to build out a book like that, and they didn't like it because it was all from a first-person point of view. like me as a futurist saying where I thought the industry was going. They wanted a very neutral point of view from an industry point of view. And they said, look, keep the advance. We don't care what you do with the work. So I just started printing it myself and publishing it. And I had a friend, Eric Hazeltine, who was at Disney. Well, he was, I knew him. He was running the simulation group. He used aircraft and I was at Rockwell. I knew him professionally through the aerospace industry, but He left and became CTO of Disney Imagineering, and he bought one of my books, and another Imagineer had called me and came down to my house, and he wanted to buy his own copy of the book. And I said, you know, there's one that's in the Disney library. And they said, yeah, I can't get access to that. And he said, why? He said, you know, Dr. Hazeltine won't let go of the copy. So I ran into Eric and I said, well, you know, why aren't you sharing this with the other? It's in the library. It's in the Disney library. He says, you printed it on copy paper and it accepts ink and mine is full of notes. So I've been using it as a strategic guide and I have contact names and phone numbers and other details on my copy of the book. So it's kind of out of circulation. This other imagineer, he bought his own copy and he went on to do all kinds of things by that book and I had a client, a young man, who bought one of my books and I went up to Santa Monica to deliver it to him. His name was David Blackburn. He ended up being a lifelong friend and he worked in the motion capture industry. That book was a goldmine for him. He was a really, really bright guy and he could sell the pants off of you. He used that book to do consulting work. He brought consulting work. We worked on projects together, 50-50. And I had exposure to all kinds of clients and products and projects that I never would have had on my own. I'm not that good at marketing, in spite of the fact of being hired to do it and not being that successful. But between the two of us, we did really, really well. And he was my friend until he passed away a number of years ago. inspired me to do more and be more and after the source book selling that and going to SIGGRAPH and setting up booths in virtual reality world and speaking at conferences I was selling books I sold one to Steve Wynn's brother who runs all the resorts out in Las Vegas and he ended up doing all kinds of VR projects from discovering people in the book to help him do that and Other celebrities and famous business people bought that book and it was like a nexus of information for the future for them. It was very gratifying to have customers tell me about that and for me to really put all my intelligence into it. My whole life has been based on sharing information that way and hoping that people do something with it. You know, if they bring me in on it or they need help, I'm there for it. But after the source book, I started teaching. I taught at Cal State Long Beach, advanced virtual reality course, graduate course. And then I had other speaking gigs, a lot of major conferences, the World Science Fiction Convention. And a bunch of individuals contributed to what became my Wikipedia page. And so there's some historical timeline there of conferences that I've spoken at that were listed, the ones that seemed interesting. And publications, I became an executive editor for, associate editor for Virtual Reality Systems Magazine out of New York. I wrote articles in Computer Graphics World. And I was a... a proselytizer, I don't know what you want, a promoter of the tech who also had hands on. And then, let's see, where does that lead me? More or less to present day where I continued doing that for the rest of my life. But around 23 years old, I got some news that might mean that I may not live very long. And without going into a lot of details, it really was an existential crisis. I thought, you know, everything I know, what am I doing? And I came up with the idea of virtual immortality. The whole concept of life archiving and re-simulation using available data of an individual, a living individual. And I was going to use myself as sort of the guinea pig and be the spokes guru for virtual immortality. I started digitizing myself with 3D acquisition technology. I became an expert in 3D scanning tech, which I had already investigated for the source book, and I had a whole chapter on it, but I knew all the people, all the various companies building technology, primarily a company called Cyberware, and I got scanned young, and I got a copy of my data, and then the whole rest of my life I made it a concerted effort to be digitized in the next version of scanning technology to scan my person and to hold them hostage until they give me the data and then keep the data safe somewhere. And so I've been scanned probably a dozen times since I've been 23 years old over a course of five to 10 years each time, almost 70 now. I've done my own 3D scanning for the last 10 years using portable devices. mostly of other people and other things, a few here and there myself. I wrote a paper and I published at a virtual reality and disabilities conference in 1992, my first published paper, using virtual reality to document human existence. That's the seminal generational paper on virtual immortality that has been written that early. There have been examples in science fiction, and I used to give sessions at conferences and show to these examples all these wonderful movies where they had these effects of people being scanned or something. One of the best movies was Looker by Michael Crichton, so I use that all the time. Susan Day goes into a scanning system. What's funny is the way these figured into the plot of each of these movies was usually very nefarious, the 3D scanning and the immortality of life. And I met the director, Brett Leonard, through friends in Santa Cruz. And he tapped me to help him develop some ideas for the movie The Lawnmower Man. And at the time, I brought him some drawings and diagrams. I had developed a system using this three-dimensional concentric helical exercise machine with a VR visor in it. So that was my design. And then he got it, and then he showed it to some of his other designers and people that built it into one of the primary effects of the movie. And there were lots of other things in the movie. And if you go back to Lawnmower Man, you get a copy of the DVD. the director's commentary. I think I'm the only person that he mentions or gives credit to in the whole entire industry. But he mentions me by name as this brilliant person that helped him come up with some of these ideas. And at the time, it was just a casual lunch with him and his partner, who's no longer with us, Jamil Everett. And they were just fascinated with my notebooks and my source book. And I made a contribution there. I didn't even realize I was doing it. It was part of the mantra of my life of giving, giving, giving, sharing. And who cares where it goes? It doesn't matter. If I keep it to myself, there's just no point in having it. So I became friends with Brett. I've been lifelong friends with him. I made his Wikipedia page, which I was surprised he didn't have one, but he had a substantive body of work there. I'm a master Wikipedia editor. I've been doing this for years for other people that I thought deserved to have pages after all the work that they've done in their life in electronic music, computer graphics, and in humanitarian issues as well. I can't even remember some of the people I've done, just enough of them. For me, it was like doing a crossword puzzle or homework that was worthy homework, more on the spiritual work side than anything else, but very detailed, very fact-based. So after Lawnmower Man and the Sourcebook, I started working with SIGGRAPH and people in the motion capture industry. My friend Dave Blackburn ended up working for Motion Analysis, which is a major motion capture company. And my partner, who I met in the early 90s, who I've been together with for over 30 years, he was a Broadway actor and a legit baritone and a very gifted singer. And he was fascinated with this technology. You know, people are sapiosexual. They're attracted to people that are very intelligent. So he was attracted to me because of my intelligence. I wasn't a bad-looking person at the time either, But I didn't know much about theater or know any singers. I grew up with a close friend who was very musical family. I love music. I gravitated towards people like that. I always liked them. They're always friends of mine. So we just had a great chemistry. And he and I both became interested in application of technology for actors. And we started what was called the Performance Animation Society, one of the first special interest professional groups for actors in Hollywood to learn and utilize motion capture technology and then I also kinda got deep into the ethics of owning your own data and I wrote a seminal article in Computer Graphics World called Whose Data Is That Anyway? and it was about actors being scanned and their motion capture being captured and then the studios owning it or the scanning companies owning it and not being presented to the actors as an asset that belonged to them, or that they could utilize or repurpose in some other project. And so I consulted with the head of contracts at the Screen Actors Guild on trying to help them formulate contracts to protect the actors' interest in these assets that they were being asked to do for movies. In some cases, they weren't allowed to even be considered as a principal actor unless they agreed to be digitized. Lucasfilm started doing that pretty early on. I also was known for going to SIGGRAPH every year and doing something at SIGGRAPH, but I would drag people into the 3D scanners that were being on the show floor, and then I would demand that they send the data to me, and then I would take custody of it for whoever it was that I dragged in there, if they were an effects person or somebody famous. Digitized Timothy Leary, I became friends with Timothy Leary. and the Mondo 2000 crowd up in the Bay Area. And I met my friend Daniel Kotke very early on, who was one of the three co-founders of Apple. Not technically, I mean, actually, but not technically. I mean, he was Steve Jobs' best friend, who Steve disowned for caring for his common-law wife and his daughter, who he denied paternity for. And Steve treated Daniel horribly and locked him out of stock in the company. Never fired him. He worked for Apple for decades. But he didn't get any founder stock. And Steve Wozniak, who's just a sweet, loving man, thought that was very unfair. And he gave Daniel some of his early stock. And he's been able to at least have some of that in his life. But Daniel and I became very close friends. And he's still a beloved brother to this day. And my life has been a lot about the people that I've met along the way and having them become important to me on a lot of levels that didn't have to do with business or commerce or technology. Of course, we were all sort of technology-oriented in some way, and that's one of the reasons why we all liked and enjoyed each other's company. And I was always proselytizing VR and AR and I built my first wearable augmented reality system in actually 1982 using a private eye display and a belt-based computer and started trying to figure out what kind of applications we could use this tech for. I wasn't interested in the military. The one idea I came up with was managing guest lists at celebrity nightclubs for VIP doors, because they were all like paper lists that they'd have to flip through. I used to go to Studio 54 in New York, and they let me in because I had model good looks or something like that. And I see the lists and lists and lists going through to find somebody's name, 10 minutes trying to find somebody's name on the list. I said, God, how do we optimize that using tech? So that's why I built that system. It was called the ID, E-Y-E-D-H-D, to identify somebody for entry into some secure area, and this particular case, nightclubs. Well, it wasn't a really good business idea because nightclub owners are very sleazy business people. They don't want to pay for anything. They wanted to charge me to use it at their nightclub, so for promotional purposes. And I did some tests, and it worked really, really well in that context of letting people in. And I had come up with all kinds of other add-ons for using a camera and creating visual identifications and other things to help the doorman figure out who somebody was important, even if they didn't know who they were, that they were important enough to let into the VIP list. comp them and escort them to a table using indoor navigation, just amazing stuff. And it took me a while to realize that I was an inventor and that even though I didn't like the idea of having patents and servicing patents with fees for decades and litigating and trying to license stuff like that was not my thing, but it didn't stop me from wanting to invent things and be creative. And All the while, always digitizing myself the first chance I could get. I would see a new scanner. Scan me, scan me, please, please scan me. And taking the data and then squirreling it away. And, you know, as the technology, I kind of sort of gave up on VR for a while. There wasn't any funding. And... it turns out that you know the internet happened and then we had metaverse online and everything went to 2d and nobody was that interested in 3d wearable tech was too expensive and too complicated it wasn't efficient enough to do metaverses i mean i got involved in a lot of the early metaverse stuff to try to prove out 3d and i mean 3d vr and i got involved in some business ventures that came and went and and other partners that crashed and burned and other people that became friends. And so my life has just been sort of serendipitous, dipping my toes into new tech and new people and their minds and their creative sense of self. discovering some of my own gifts in this particular area. And I ended up continuing to write. I ended up teaching advanced virtual reality lab at Cal State Long Beach. And it wasn't particularly successful as a teacher because A lot of the students, they were sold on the idea that they would learn virtual reality and they could go get jobs doing virtual reality at a time when very few companies had any virtual reality tech in their facilities. Just Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, Rockwell, the big aerospace companies had them. The students wanted to, they thought they would just go out and get jobs in the VR industry. So they were kind of, anytime I wasn't talking about teaching them or getting a job, they were pissed. And the more I wanted to talk about the culture and the science and the art and the history of it, they were bored and felt there was a distraction from them. So I had met Mort Heilig pretty early on also, and when I discovered who Mort Heilig was, I totally promoted him and helped him get speaking gigs at all different places, and I have video recordings of Mort Heilig nobody's ever seen before, whole lectures. Mort Heilig of the Sensorama. Yeah. So he's considered one of the grandfathers of virtual reality, along with Tom Furness. And he became like my adopted father slash grandfather. We were pretty close. And I did a lot of conferences with him, got him on a lot of panels. He was very curmudgeon-y. He had been treated very badly by Disney after he had been inventing stereoscopic photography and all these other things for Disney that they They just thought he was too autonomous for them. They wanted to own everything he was doing. And it's like, no, I'm following my own patents. They're not going to be Disney patents. This is stuff I'm doing in my own invention lab. And I'm showing it here at Disney because I want you to use it. But no, they wanted to own it. And so he got in a tip with them and they let him go. And that was like a sore point for him. He was this wonderful inventor man, this kind old Jew from New York that had done little movies here and there. He was just an amazing man and a lovely man. I think he needed promoting, and so I got him involved in every conference I could. That lifted him up a lot, and he ended up getting recognized and becoming celebrated. People like Jaron Lanier had figured out who he was, and other people in the industry that were doing things all figured, oh my God, Mort Heilig, he's really the grandfather. He had all the patents and stuff to prove it. Timothy Leary was absolutely fascinated with it, and I had 3D scanned him, and the folks from Silicon Graphics ended up deleting the data. I met a lot of people through his network as well, who were spiritualists, And they were all fascinated with the potential for technology. Certainly, I was mostly talking about virtual immortality and 3D scanning and human simulation to these people, like in a profit way, like a profit. And they were very responsive to it. And I was, oh my God, this is a fantastic thing. So I created an idea of what's called personiform, which is, you know, we're all struggling to find a word to describe some of these things. So a human simulation, photo-realistic of a real person with a real personality that is imbued to animate and re-simulate the person. In my mind, a simple word would be personiform. So you would have a personiform that would live on beyond your corporeal existence. Well, it's a word. Somebody else invented it. It's not a commercial word. It didn't really catch on. I just had to kind of promote it and use it as much as I could. It hasn't become a meme, but it could be at some point. Just a reductionist word to describe a more complicated thing that we all can grok or understand when we witness it. So I thought maybe we should put a scanning facility together and start digitizing and scanning famous people, celebrities, political figures, sports figures. And I got a P.O. box on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, and I had intended on building just a beautiful scanning system that would be run out of a studio right on Rodeo Drive, almost like a salon, a scanning salon. And I was working on a design for a 3D scanner with multiple motors that all had tuned frequencies. And the scanner, the way it 3D scanned you, it would celebrate your body with these musical tones as all the motors spun up to speed and changed their speed. And so it was like a transformational experience of being scanned. So a famous actor would come in there and sit down and, you know, they would get their makeup and get right and stay still. And this thing would like be going into an x-ray at a hospital, but not a clinical setting or like a beautiful salon setting. and celebrate their persona in the process of the digitization task. And I never got to build that system and I never got to build the, you know, have the facility. I wasn't born rich or anything. I was sort of upper middle class and didn't earn enough money where I could afford to do this stuff. I've had other people that I knew that were wealthy and they took a stab at doing things in their life that they could fund and they achieved various levels of fruition that I was not able to achieve. Maybe it's just, you know, a lot of this stuff is just early on that I came up with it. It just wasn't its time and maybe in the future that's what will happen. Nowadays, we have companies like Meta, with their whole facility in Pittsburgh, building huge machine learning models of humans that have been scanned in a gigantic photogrammetric volume. We have Paul DeVevick's work in the light stage that was built at USC and then moved to Google. Shiram Azadi, who we're in that group now, was just given a presentation at TED using the new glasses. So this weird crossover between 3D scanning and motion capture and VR and AR has been going on for a long time. Some of the same players move through the ether of these technologies, and I'm one of them. who's adopted newer technologies. I'm always an early adopter. And the AR systems we have today are like a vision of many of us at the early time. VR had envisioned what happened at some point. I worked with a system called the Virtual I.O., which was actually an AR overlay system, but you could put a little shroud in front of it. And I used that to put a lot of people through VR, build a VR system with it. And I could also do tracking and overlays, but Like I said, it was very early, and it was not easy to get people excited about the idea of wearable AR as an everyday thing. It had to be hooked up to a high-end machine. And even today, with all the promise of VR and standalone VR, some of the most important and coolest tech that I would show somebody is hooked up to a very high-end computer using a tether. and the device on your head is basically a display system that's doing tracking, and there's not anything more magical about it other than maybe, in this case, it's tracking your hands with different technologies. I actually came up with the idea, which was called constellation tracking. I called it scatter-gather. So, what Scatter Gather was, the emissive LEDs would be sequenced on the externality of the virtual display, and then cameras would be looking at it with infrared light, and they would compute all the points moving in the cloud, and that would basically describe the orientation of the system. Some of the other things I came up with were the persona booth, where you stepped in the booth, and it basically said, turn right, turn left. And it did photogrammetric pictures. It did 3D scanning. And as soon as I could get my hands on 3D scanners that were in portable devices, Google Tango Project had the Asus Zenfone AR. They had the Tango tablet. They had the Lenovo Fab 2 Pro, all with 3D time-of-flight scanners. And that became my Andy Warhol moment. The one thing we learned from Andy Warhol was he always said that if you want to take pictures of celebrities, bring a really crappy, like, Instamatic camera with you and just act like a kooky fan and just... Oh, can I take your picture? Click, click, click. And so the celebrities, if they saw a big professional camera and you looked like you were a photographer, they didn't want you to take your picture, you know, back in the day. But if you had this little handheld junkie camera that everybody can buy at a drugstore, and you took their picture, they didn't mind. And so one of my friends living in New York at the time was Patrick McMullen, and he, early on, he was part of the Andy Warhol entourage as well, and we would go out with Andy, and we would all get into clubs with him and stuff. If you were with Andy and everybody was holding hands, that was holding Andy's hand, like 15 people all holding hands, and Andy's the one in the front, you'd all get in the club. You'd all go right into the VIP entrance without paying or anything. So I always tried to get to the factory before they all left to go on their club junkets, and then make sure I was holding somebody's hand and get in. Otherwise, we would get stuck. We would be outside, and that would be it. Someone would have to come get us. But Andy's philosophy to Patrick was this Instamatic thing, you know, bring an Instamatic and the celebrities will let you take pictures. Well, Patrick amassed thousands of pictures of celebrities going all the way back to the 80s. And he's published books about it. And he became a very legit celebrity photographer. He's really an A-list photographer nowadays where he gets invited to these events and he's like the only photographer they let in. But he can use any camera he wants because he's Patrick and they know who he is. that ship sailed, you know, and he got on it. So I had taken that same philosophy that I had learned and applied it to 3D scanning, like gorilla 3D scanning, like you do gorilla interviews. I'll bring the 3D scanner with me, and I'll say, oh, can I do a 3D photograph of you? And they're like, oh, what's that? Oh, let me show you. I walk around them, I scan them, and I bring it right up, and I spin around their avatar, and I show them, and they're like, oh my god that's fantastic and then I email them the data of course they don't know it's point cloud data it's a file they don't know what to do with it I could describe what to do that I could give them a viewer they just they don't get the idea that this is like sacred data that came out of this wonderful sort of Gift that this man this little odd man Decided to scan them with this one device that he's got in his pocket of 10,000 people around them Nobody has this device in their pockets like a secret weapon and the idea of scanning other people and being like I don't know a harbinger of things to come and taking the time and recognizing them and being charming and enough to allow them to do it and just became a whole philosophy to me. So I have thousands of 3D scans of people and places, some of them famous, some of them since passed on, and they're all pure point clouds, which means that there really is very basic data. machine learning, computed polygonal models based on photographs that have been reverse analyzed from points of view. You know, photogrammetry can make beautiful models and they look really good and it's cheap and dirty and easy to do. But real 3D data is point cloud data that comes out of a, you know, a handheld scanner. And that's been my philosophies. Build a device, build technology that celebrates your physical form in the present moment of existence. And treat the opportunity to digitize somebody as a sacred moment in time. And so this 3D data that I've accumulated is something that you would use in a time machine. So if I wanted to go revisit a younger version of myself, I could bring it up. And some of the demos, one of the ones that I showed in my talk yesterday, were a 3D head of Richard, of my friend Alan, and myself, all in an augmented reality pass-through environment. So walking around them, looking at these people, it was one of the demos that I gave. And there are other demos that I show where you can input this data. And in some cases, like there's a program called Resonite, which is a 3D metaverse that runs on a high-end machine, but it works beautifully in VR. I can import the raw point clouds of people without having to polygonize any of it. And in some cases, it includes sensor noise. I mean, it's a real sort of poetic technique to digitizing somebody with this handheld technology. There's a way to do it. There's this very magical sort of painting that you do to get really good data. And if you don't do it well, you do too fast or too slow, you bring the data up in a program like MeshLab, and you'll see outlying points and sensor noise and spurious reflections. that you manually have to go sort of cut and shave out of the scene. And the scanners aren't intelligent to know that you're scanning a person, to add detail around the eyes and the mouth, and not to use a lot of detail or real estate on other areas of the body that are just surfaces with clothing or like that. That's where we're headed and that's where I'm working on now is trying to develop specifications for AI machine learning systems that understand point clouds, understand 3D data and acquisition of objects and people in the real world. And they can take any kind of scanner or sensor data that's been acquired by anybody in any technique and they can clean up that data and regularize it and make it more efficient, which leaves only the essential elements that are important to human perception when you render and re-simulate the data. And a lot of things going on in AI right now with taking single photographs and taking video and giving prompting to AIs to do animated stuff. So I showed some of that yesterday, made a bunch of people laugh. I've been working with spatial displays to do volumetric imaging. I've been working with voxelization for a long time, the Gaussian splats, NURBS, NURFS, all various techniques of displaying 3D data. And many of them have evolved to try to overcome technical limitations of rendering and density of information. And the Gaussian splats into the scan of Earth was something I showed very briefly, where people have digitized statues in places around the world, put pushpins on a globe interface, you spin the globe around, grab a pushpin and it takes you right into the Gaussian splat. You can wander around and look at it. This is great for monuments and museums, historical archiving, virtual museums. The idea of having virtual museums with living, talking avatars of real people, to me, is just a wonderful and beautiful way of people experiencing the past, the present, possibly the future, and doing it with data that came from some real person in some real time in the real world. And that's where the time machine aspect is of it. But nowadays you can feed a photograph to a number of programs, TripOSR, Hunyan3D, I mean there's half a dozen of them I listed in my talk yesterday where you can just feed it a couple of photographs and make a beautiful 3D version of it without scanning them, without having to use point clouds. And so our need for the kind of human simpatico that you desire from your technology is going to take twists and turns as the technology takes different directions. And what ends up being commercially viable and what everyday users that don't have a lot of technical knowledge will end up enjoying and using and relying on for legacy memorialization in their life may look very differently from where I started with manually 3D scanning people. But I think we as humans are sort of universally acclimated to the existential panic over loss of life and loss of loved ones and fear of death, which is the continuum that is, you know, fear of death of other, fear of death of loved one, fear of death of self is sort of the ultimate fear of death. And some of us have health challenges and we've experienced fear of death of self. And so we've ended up dwelling more on that end of that continuum. Others have witnessed fear of death of us. Some of us have lived beautiful lives and hardly know anyone that's been hurt or died or other than just living a long old life and passively going to sleep one night and that's the end of them. But having a Wikipedia page, memorialization, accumulation of assets purposefully for life archiving and human storytelling and re-simulation and virtual immortality. That's the philosophical world I live in at this point. And my story is interesting and all the sort of privileged places that I have done things or touched things or discovered in my life and the motivational factors for moving me on my path in different directions to get me to where I am now where my work, if people look close enough at it, looks as if it's significant enough for me to be given something like an XR award. This little XR conference that generally to the world very few people know anything about. to us is this fantastic nexus of things going on, of these brilliant people, the stuff going on, stuff on the show floor, people giving these sessions. I'm just swimming in gratitude over the fact that people are recognizing this, that they're stepping out, they're showing what they're doing, they're doing the work, they're publishing, they're doing products and projects and artwork. I don't feel alone. I feel like I'm really in a family of people that matter and that they're doing really valuable work. Certainly your aspect of where you play and recognizing people and taking the time to interview them and create stories for them. will have a much longer lifespan than a lot of things because maybe just this one interview is enough information for an AI to learn about me. I've been doing experiments with Google LM, you know about Google LM, feeding it documents and information about me and having it have a conversation. And Richard reminded me with somebody we were talking to earlier today, Some of the Google ALMs I've done in my work recently, one of the experimental features of the Google ALM is you can interrupt the conversation and then you can start talking to it as if you're talking to the two people. And I've had some information on Wikipedia, a few other little papers, my original paper in 1992, through very select things for it to have knowledge about, for them to be talking about. And then I interrupted it and I said, hi there. And it's like, oh, hi, you know, the two characters. I said, this is Greg Panos here. I'm the real Greg Panos that you're talking about. And the way the model responded, they were like just honored and surprised. And they were like, oh, my God, it's Greg Panos, yourself, the real person. Oh, how wonderful. Oh, we were just talking about you. And so I started answering questions and they started interviewing me. And I recorded this interview. Richard and I were blown away. We were just blown away how this artificial intelligence was just sort of doing as commanded to absorb and to discuss and then to discover in real time, real time interaction with myself. And, you know, granted, it was a very sort of sandbox, little tiny little sandbox we're working in. But to me as a human being, to hear the interview played back and I taped it and listened to it, I felt, I just, I felt glorified, you know. And I thought, my God, you know, if that can do that for me, this has a big value to everybody, any person with any life that's living that speaks language. that can talk, they may not scientifically or culturally amount to much in their mind, and yet this technology has the ability to make them feel better about who they are and their meaning and their existence and their life and the loved ones in their life and whatever they share, and that's a real positive aspect. I don't dwell a lot on, like the recent panel you were just on, I don't dwell a lot on the nefarious use of deceiving somebody to steal from them or to make them kill themselves or do something horrible or attack someone. Of course, this all could be used very bad. And certainly my work, I mean, some people could look at my life's work and say, oh, this is just a terrible thing that this man did. This idea of the stuff that he generated, wanted to be doing, is just horrible. Nobody should ever do that. sort of Luddite point of view like let's smash the machine so you know we don't ever have to encounter this threat and I think we're kind of beyond that now I think we're getting to a point where the machine learning models are they have so much capability and certainly when you augment them with retrieval augmented generation are you familiar with that is yeah when you add personal data to the general database and then it can relate stuff from the augmented retrieval information to a lot more other published works that it had absorbed and categorized to make the conversation wider than it would be if it was just confined to just published works or documents. So, you know, the idea of Personaform, when I realized, you know, I'm not going to fund this. Celebrities, you know, they're already famous. Everybody's kowtowing to them. They get everything. Yeah, they're important. They should be digitized. A really important part of our culture. But someone else needs to figure out a way to pay for it and do it and convince them to do it. And now we have the agencies like Creative Artists and Endeavor that have relationships with 3D scanning companies. Creative Artists, it calls it what's called the vault, where they do this huge amount of work, 3D scanning and motion capture for their clients as a service. And then they build a database, you know, that model for them to repurpose them as actors or give them sort of lifetime experience. beyond their actual physical career. And some of these people get old, they lose their hair, they get fat. I mean, Russell Crowe put on a lot of weight and they could make a shrimp, you know, optimized version of him and put him in movies. And, you know, it's part of the What I don't like about it is part of the commercialization of profiteering and that whatever reason drives the technology for them to adopt it. But one of the people who runs one of the big agencies Brian Lord, I made a Wikipedia page for him like 10 years ago because I just saw some interviews of him. He seemed really likable and he was really liked by people in the community of actors and George Clooney and people like that. He's the agent for some of the top actors in the world and one of the founders at CAA. I figured this is a man who will get behind the 3D scanning of the actors for their clients. That's just part of the everyday DNA of what they do. And I've never met him. And I made the Wikipedia page for him. And just like a year ago, I saw him giving an interview about the vault and what CAA had been doing. So my vision was for this man to sort of take up the mantle and have the bravery to start talking about it as something that was legitimate and worth doing and he did and he's working with another facility. My idea would be to go to CAA and build their own in-house facility and then have somebody who is just the right temperament to work with the actors to do the digitizing and the like but not be formed out to another company or not to acquire another company and just send them across town to some other facility but And also to build out the scanning area as this place of spiritual celebration with specialized machines that were designed to scan that are beautiful in the way that they operate and poetic. So it's an experience for the actor. It's not just this cumbersome step, a bunch of like cookie makeup things that they have to do to put up with clown makeup for six hours before they play a clown in a movie. nothing like that at all, something very spiritual, create an emotional response. So I don't know if they're gonna get there, and that's what they're gonna do, but that was what my vision was. And that would be fun to meet him someday and let him know that he has a Wikipedia page because I intuited that he might be a person that would be open to that and get behind that, and it turns out that's exactly what happened. He'd probably be thrilled to hear it, and probably the only thing I would want for him is to sign up my partner, you know, so he has an agent, so he can do other projects, you know, that are all sort of legit projects that aren't experimental works. I engage Richard in experimental work, and... He sang Uncanny Valley. We wrote lyrics for the song Uncanny Valley. He sang it and I just showed up my talk yesterday of him singing it using a Azure Connect, volumetrically capturing him while he's singing it and then reflecting it as a three-dimensional stereoscopic volume in the looking glass. And people loved that. They watched it yesterday. I've had him doing performances capturing him as a singing avatar and then exported the data and then put it into AR and have him standing in the middle of the living room singing and performing. So the beauty of what's happening is a lot of this stuff that I dreamed about that I thought might never happen We're getting to the point where you can go buy at Best Buy, plunk down $500 or $600 on a MetaQuest 3, and there's enough free software for somebody that's artistically inclined and has enough technical curiosity to find these programs that are free experimental artworks, more or less. but are real tools and start utilizing them to create assets for things that they want to do creatively. For young people, you know, that have talents, they can sing or act. This is the news like virtual dollhouse for them or the virtual little proscenium stage that's made out of little pieces of cardboard that might change the directory or their life. It might convince them that that's what they want to do or that's what they don't want to do. They want to go do something else. I just wish that they lived in a society that wasn't organized around capitalism and the fact that they have to have a job to live. They need a roof over their head and that requires rent. They need a job to be able to pay the rent. I love the idea of universal basic income. The whole idea of money and wealth is just a virtual construct to begin with. There's no intrinsic value in it. Even gold itself, gold bars, has nothing to do with any of that stuff. Caveman time, gold bar would be glittery. They might kill each other over the fact that one or the other would want possess the glittery thing and I think that's where the whole idea of money and owning property and investments and all that is unfathomably just hard to grasp for me on a spiritual level that we live in this world and I never grew up, my parents never pushed me to be a doctor or a lawyer or somebody that made enough money to stand on my own. I've just been lucky enough to drift from one situation to another where with some amount of minimal attention I was able to earn enough income to have a roof over my head or have a car or have stuff to eat. and spend the whole rest of my time just wondering and playing and discovering and learning. This past year I've had to learn how to modify and play with Python code to get it to run locally on a machine to do machine learning and image generation and 3D. model generation from various types of media and I'm not you know I don't know how I'm not that technically smart I guess compared to other people I'm very technically smart but I hang in crowds of people that are so much more intelligent than I am on a technical level in math and science that I'm in awe of them, but they motivate me to learn more and do more and to discover on my own and to uncover little details of stuff that will get something working, working well enough to show it to somebody. I'll show it to relatives and they'll think I'm a frigging genius for this stuff. And I try to explain to them that their kids can figure this stuff out quicker than I can. and that I wasn't born with some special thing. Maybe I was a bright child or I ate correctly or my mother didn't have problems during her gestation. I mean, any number of things could happen to somebody to disable them to being on an equal playing field other individuals that never had anything happen to them that grew up healthy. And so I'm a baseline person. I think of myself as a baseline person. I don't think of myself as an exceptional person. I think I've come up with some exceptional ideas in my time, but in 10 years a lot of this stuff will be very obvious and won't seem unique to anybody. and will be integrated into levels of our society that is commonplace and easy to understand or grok, for lack of a better word. And the children of the future will figure this out very easily. You know, I really enjoyed the panel you were on. You were kind of like wrestling with some of the other people on the panel. I mean, Lewis made most of his money litigating patents in haptics. So I remember Lewis from early on and he got the haptic patents. I didn't realize, you know, having a patent and original basic technology was like having a ticket to being rich. But the reality is you'll only get rich from it if you want to become legally nasty over people that are coming up with the same things around the same time that start using them. And you filed some paperwork earlier than they did. And our government and our capitalist society says, that's yours, that's your invention. And you have to spend money and lawyers and you have to make people's lives miserable for them to say, I give up, I will pay your licensing fee or I will stop what I am doing. And I've known a number of people that have done well financially that way. And some of them are brilliant inventors. I mean, he certainly is. I love the brilliant inventor side of them, but the business side of them with the lawyers and the business people behind the scenes that are taking those inventions and capitalizing on them, for lack of a better word, and litigating and suing and creating havoc is the weeds I don't want to get into. If I had patented a lot of what I did, I would have been able to do a lot of that, but I never wanted to go into that space. And to be honest with you, a lot of what I came up with was so early, patents only last 17 years, they wouldn't be valuable. I mean, they would be listed as sources on other patents. And some people wouldn't be able to patent things that I had patented or disclosed because the information exists that it had been done before. They would have to do something a little different to get a patent. So it might be harder for people to do that. And I've known inventors who didn't like the fact that they hate science fiction because science fiction shows this stuff years before they're able to actually build up a real prototype and actually patent something. and then they have to fight over the idea that who had the idea first and was it possible for someone to build it earlier than they did and part of the idea of IP is that not only wasn't thought about but it wasn't practical to build and so we'll give you the patent because you built it at a time that you could and you patented it at a time that you did and So, you know, here we are, you know, in this world where information sharing is king and some people run off with the goods and make some money with it and they don't talk about that. And you wonder how they got into a situation where they had as much as they did. And they'll never tell you, you know, you have to do some extra homework to find out. Is this somebody, do you want to be like them and do the same thing? They'll probably like welcome you in and help you do it. Most of the time they won't say anything about it and you'll have to find out for yourself and then you'll be like, well, that's kind of awful. You know, I was impressed and now I'm not. And I imagine it's something you encounter a lot that you learn things and you kind of shake your head and say, well, that's disappointing. I'd hope for more or better. Any more specific questions?

[01:09:49.383] Kent Bye: Yeah, well, just a question I like to ask all my interviewees is, what do you think the ultimate potential of all these XR, spatial computing, immersive technologies, and spatial capture might be, and what it might be able to enable?

[01:10:03.442] Gregory Panos: Yeah, so that's a good question. In my mind, and I'm kind of single-minded about it, it's about life experience and a proper memorialization of it and discovery of those data lines, lifelines of information. I have a little video I did in 1994, I think it is, and I show it all the time. It's my original Persona Form vision. I'm like 27 years old in the video. And I really, I describe it very, very succinctly back then about why people should digitize themselves, why it'll matter for them, not necessarily right now, but as things go along, and that they should scan themselves and they should assetize and create assets on a regular basis with a sort of sense of sacred nature of the unique nature life for which they should be grateful for as evidence of self-documentation purposes. And I think all these platforms will evolve to basically process and display and give you the opportunity to interact with this kind of data. But it'll be structured in a very realistic way and reasonably model real human existence the way we understand it, the way our biology and our evolution has created us to live in the real world, the virtual world that contains loved ones and oneself and others. And it will be just a marvelously accommodating and interesting and comfortable place for us to spend time in. I mean, certainly people as they get separated and COVID taught us, you know, being alone in isolated spaces. I spend a lot of time in social spaces in VR. Every Monday, I join the XR Social Club from 6 to 8 p.m. Pacific time in VR chat. And I've got about a dozen friends that I've made in there who some of them I've only met for the first time in real life here over the last few days. Some of them work for Meta, others are artists. And I'm just blown away with the people that have come up to me and said, hey, it's Joe. It's like from VRChat. I said, oh my God, we've been hanging out for six months every Monday. And they realized that was me and they came up to me here at the conference. We got to meet in real life. But my ability to go in these spaces on a regular basis on Monday is like some total of my legitimate interaction I have. I don't go out to a lot of conferences and things. I'm in a dozen things going on here in LA over the last six months and I haven't wanted to drive up to LA for any one of them. I'm getting old. It's harder for me to drive long distances and as much as I want to be around them, I'm sort of afraid of getting sick. God, I would love to have more of these things going on in VR and everybody to be rigged up so their onboarding experience and the amount of friction that would be required for them to join us or join me would be at or close to zero. I think that's where we're headed. That's what's going to happen. You know, people can philosophize it or reject it or find rationale or to hate it or love it. But I just think it's in our nature. And that's where we're going to go. And I think eventually we'll get to the point where we'll visit our loved ones and we'll have experience with them. My grandniece will have a chance to experience me. I've never met her. She's like six years old already. She lives on the East Coast. I hardly ever go back there. My sister doesn't really like to do FaceTime with anyone other than her kids and her grandniece. So I talk to my sister on the phone very rarely and I haven't had anybody put my grandniece on the phone or on a video to meet her. I'm kind of disappointed with the way my family just, I'm at a distance from them and I'm a concept. And as long as I'm alive and I'm not sick or dying or something going on, I'm out of their mind. Every once in a while they see something I'm doing on Facebook and they wish me congratulations on the award or whatever. I don't think they really understand that much about who I am or what this is or who I'm with or who my friends are. they would probably be impressed with my social group, my circle, and the people who like me or care about me or have a sense of my work or value it. And this is true for all of us. We all have loved ones and family and we want more from them. We want better relationships. We want more closeness. We want more sharing. We want more forgiveness. We want more gratitude. And some of us get none of it and live isolated lives. Others get more than their share. Some people, their families disown them because every time they talk to them, They need money or there's an emergency and they just don't want that in their life. There's just so many reasons for relationships to fall apart. I think we have a lot of opportunity ahead of us to come together and to make new family and bring together people you don't. necessarily ever anticipate will become part of your new family. And that's been the poetry of my life. It's hard in the framing and the fact that I have a physical family. It's been more or less disappointing in that way. And I have to constantly rehash my gratitude over who I am and what I have. who my partner is and how much they love and care for me and did I have any of that because I have friends that it's been a long time since they've had any kind of relationship and they're lonely and they're horny and and the only advice I can tell them is learn how to cook and learn how to be funny and if you can do those two things you will not be alone you have love in your life And, of course, you have to get out, and you have to meet people, and you have to also deal constantly with rejection and not have it be about you. Love yourself. Love cooking for yourself. Love watching TV and laughing by yourself. And I think a lot of the technology, if you don't love yourself enough, you're not going to spend a lot of time documenting who you are in your lifetime. It just doesn't seem right when you don't do that. And if you do, you'll do it without really having a lot of friction. And not specifically for any purpose. It won't require a purpose. Because you already won the prize. You already love yourself. You already care. Your parents had you. They love their child, presumably. They want their child to love themselves. They don't want them to hate themselves or feel lonely or abandoned or any of those things. So the truth is, if you're alive and you can look in a mirror, there's somebody there that loves you. It's hard to imagine, you know, for me, people that don't have that. I think I'm really lucky that even if I didn't have a partner when I was single, I was not incomplete. I felt complete and I liked who I was and I thought it was funny and I thought, you know, gee, now I'm really happy to be who I am. And I think the technology has a lot of opportunity to help people do more of that, more of that self-discovery and self-love, and help them itinerate the things to be grateful for in their life and remind them and exercise their gratitude. and to prepare them for interaction with other human beings where the interaction is productive and fruitful on levels that they didn't specifically think about or anticipate having happen in any successful way. organically evolve because of their preparation and the experience of using the technologies to sort of have them come to terms with their own existence.

[01:18:26.645] Kent Bye: Yeah, for sure. Is there anything else that's left unsaid that you'd like to say to the broader immersive community?

[01:18:35.322] Gregory Panos: Yeah, I would say if I was giving advice, I would say find your niche, find your passion, find whatever it is that makes you particularly excited. You don't need to validate it with others in the real world. You just need to just open your heart and discover the uniqueness of who you are and what you'd like to be doing or what you witness in the world that you're attracted to or would like to do more of. or to do something like somebody or with someone that's doing some of those things. And don't be afraid to talk to people and don't ever be afraid to ask for help if you need help doing anything. It's an art to Free yourself from the fear of rejection, or being alone, or not having the help that you need. Just be conscious of the fact that everyone has a very complex life, that they are trying to focus in some way. If you enter into their space in their life, you run the risk of distracting them from their life process of quantifying and feeling grateful for the life that they have. So try to add value to other people. Pay attention to them. Listen to them. Try to figure out who they are and do the work in your mind. How can you help them do that? What can you do for them? And if you do that, then if you're hoping or expecting anything, the likelihood of it returning is really, really high. So have faith.

[01:20:11.104] Kent Bye: Awesome. Well, great. Thanks so much for joining me here on the podcast and congratulations on being inducted into the AWE Hall of Fame. And it's a real pleasure to get a chance to hear a little bit more about your journey. It weaves back through a lot of the history of VR and a lot of like key turning points from a culture perspective, the book and, and also just, you know, being involved with spatial capture for so long. And certainly we're at a The point where a lot of these ideas and technologies that you've been playing with for a lot of years are consumer technologies or at least available on consumer devices. And people can start to do their own capture and think about what's it mean to tell the story of our lives. I appreciate the way that you shared your story here today. yeah, I just think as we move forward, other ways that we can leave a legacy behind of our work and how it can be accessed by others, but also some of these assets that might be animated in other ways. So thanks again for joining me on the podcast to break it all down.

[01:21:06.459] Gregory Panos: Pay attention to your life because you'll get to a point where you'll regret not remembering it. And you really, really want to fight regret throughout your whole lived life as much as you can. And, uh, just enjoy and push your life forward and just don't live in regret. Learn from it.

[01:21:29.083] Kent Bye: Awesome. Well, thanks so much.

[01:21:30.205] Gregory Panos: Yeah, very much.

[01:21:32.725] Kent Bye: Thanks again for listening to this episode of the Voices of VR podcast. And if you enjoy the podcast, then please do spread the word, tell your friends, and consider becoming a member of the Patreon. This is a supported podcast, and so I do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring you this coverage. So you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Thanks for listening.