Here’s my interview with Joshua Rubin, Interactive Emmy-Winning Narrative Director, Immersive Storyteller, and Narrative Futurist, that was conducted on Tuesday, June 10, 2025 at Augmented World Expo in Long Beach, CA. We talked about his talk at SXSW 2025 titled Building the Personalized, Responsive XR of the Future: Lessons we can learn from immersive theater and gaming See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR Podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR Podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling, and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So continuing my series of AWE past and present, today's interview is with Joshua Rubin, who I had a chance to catch up this year at AWE. Joshua is an Emmy award-winning writer and interactive and narrative designer, narrative futurist, and so he was giving a talk at South by Southwest that he was titling, Building the Personalized Responsive XR of the Future, Lessons We Can Learn from Immersive Theater and Gaming. So Joshua recounts in this conversation, his journey into interactive narrative storytelling, starting from games, but then moving into like immersive storytelling, also pulling in lots of different insights and traditions from immersive theater and theme park design. And so he's trying to come up with these broader frameworks for how to start to blend these two realms of interactive and immersive storytelling that is meaningful, but also giving you the ability to do this idea of story living where you're actually like an active participant and not only like becoming your own character, but also being able to dictate how the story is even unfolding. So it starts to get into more of like live action role play. And we've, we've seen some of that within the context of the meta movie project with Jason Moore, but this is his frameworks and different ideas of how to start to blend these two realms together, but also pulling in all this kind of historical information from like immersive theater and gaming and writing these interactive and immersive narratives and and just really being on the front lines of this intersection between theater, gaming, and the future of storytelling. We also dive into a little bit around artificial intelligence, and my mind was really preparing myself for this larger debate that I was going to be having at Augmented World Expo on the last day. It's a whole Socratic debate around the future of immersive tech, which is essentially like two people that were pro AI and two people were a little bit more skeptical in terms of just being more cautionary, but also recognizing limitations and all the ethical transgressions, but also the potential harm that can be done in the future for, you know, the different paths that we're going down. So it's a much broader discussion, but it comes up within the context of this conversation. And also as I was preparing for this larger debate, which I'll get to here later in the series. So we're covering all that and more on today's episode of the Voices of VR podcast. So this interview with Joshua happened on Tuesday, June 10th, 2025 at the Augmented World Expo in Long Beach, California. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:02:40.002] Joshua Rubin: Hi, I'm Joshua Rubin. I am an Emmy-winning writer mostly known for video games. Assassin's Creed II and Destiny and Telltale's Walking Dead and Outriders are some of the games I'm best known for. But I've been working in VR since 2016 when a short VR film that I made with Magnopus and Nokia called The Argos File won the Proto Award for Best Live Action Experience and premiered at the Venice Film Festival. That was kind of the first thing that put me on the map and opened a lot of doors for me. Because of that, I was able to create and be the narrative director for a sequel to Groundhog Day at Sony, which very few people played. But it was a continuation of the Bill Murray movie I got to work with Danny Rubin, who had written the original film, and it was incredibly funny. One of my favorite things I ever wrote because it had no zombies or robots getting shot in the head. It was really about love and family. These days, I am the story lead at Another Axiom, which is the company behind Gorilla Tag, and I'm the story lead for Orion Drift, their next big game. You know, Gorilla Tag is the first $100 million VR game. I'm so glad that they exist and have shown that there is a massive market for really beautiful diegetic VR games that create spaces and community for people to be. And these days, I'm really, really excited about location-based VR. That's really where most of my passion is going. I got to write the location based VR experience based on Black Mirror. And I am working with Felix and Paul on their next location based VR experience, which is based on a massive Oscar winning sci fi IP that I cannot name.

[00:04:32.426] Kent Bye: Yeah. Nice. And so maybe you could give a bit more context as to your background as a writer and a journey into both video games and, you know, what really drew you to the more immersive qualities, interactive participatory dimensions of storytelling since they can be oftentimes opposed to each other. So just curious to hear a little bit more about your journey into this space. Yeah.

[00:04:55.369] Joshua Rubin: Well, let's see. I was always fascinated by non-traditional forms of storytelling from a very young age. I've told this story about how my parents took me to a haunted house when I was five years old, and I remember In this one room, the strobe lights were going off on these brides of Frankenstein, covered in blood, and suddenly one of them reached right over the fence for me, the little fence that was supposed to be the proscenium, and I screamed like only a five-year-old can scream. And, you know, my parents, you know, considered all of their parenting choices as they rushed me out of there. But, like, that moment was so visceral that it has never left me. That feeling of the fictional world breaking into our world, and becoming real was so thrilling that I feel like I've always been looking for that. In college, I ended up studying what we now call immersive theater, what we were then calling performance art and the theater of images. I was studying the history of groups like the Wooster Group and Malbou Mines and the Living Theater and just having my mind blown and also getting to make it. I totally bluffed my way into senior level classes when I was a freshman and was making really outrageous pieces of experiential theater that would happen kind of all around you. One of the very first pieces I made, I think it was called Standing on the Edge of a Beginning. And in it, there was a room that I had found in the library building on the campus that had no doors and no windows, just stairs going all the way up and then it would end. And so I dragged a bed up there and a slide machine and covered the stairs going all the way up with debris and would have the audience come in and make their way up through the stairs while an opera singer was, you know, her voice was echoing through the chamber. At the top, there was then this whole death and rebirth struggle that would happen inside this room at the top that was lit only by the audience members holding candles around the bed. There was only room for the bed and the audience and me, the actor, with my hair down to the middle of my back in the middle of it. You know, probably a terrible fire hazard. Definitely a fire hazard. But it was amazing and it was so immersive. And so that was kind of one of the first things that I did. I then ended up going from performance art to Hollywood, which was not an obvious step. But there was part of me that also had always been obsessed with Steven Spielberg and James Cameron and wanting to be a filmmaker. So I spent years living in the Lower West Side. you know, the West Village, writing a screenplay over and over and over while doing all this weird theater. And my life probably could have gone either way, but the screenplay finally reached a place that it felt done, and it won the Nicholl Fellowship, which was a writing award that the Academy Awards does every year for best unproduced screenplay. And because of that, I got to go out to Hollywood and have kind of my pick of agents and producers. And I managed to start a film career that I managed to then have a film career for 10 years without ever getting anything made, which is kind of a classic Hollywood story. I sold scripts. I got hired onto projects. I sold TV shows. But the first thing that I ever got produced was Assassin's Creed II. And that happened by a total fluke where a guy that I had written a script for for free at the beginning of my career calls me up out of the blue and says, we are six months from ship on a game. I'm a video game writer. Now we're six months from ship on a game and I don't have a script and you are the only writer I've ever liked working with, which was a great lesson to me. And always say yes to everything because you don't know where it will lead and always be someone that people like working with. And, you know, Assassin's Creed II, you know, took my career in a whole other direction. And I was very lucky to figure out how to keep hustling my way from one video game job to another after that and building a resume that, you know, now seems to mean something.

[00:09:15.213] Kent Bye: Yeah, and this year at South by Southwest, you gave a whole talk sharing a lot of your ideas around immersive storytelling and really appreciated all the historical references that you had in there, but also a bit of your framework of the different considerations as you're writing and trying to live into this aspiration of story living, which is what Vicki Dobbs-Beck coined from Island Immersive. But just this idea of story living, that you can actually be a part of a living, breathing story story world and maybe you could just elaborate on from the video games which is already a part of world building and you're have some agency but there's not like the true amount of like let's say narrative agency where you can really decide where the story's going to go and so yeah it seems like we're moving into a space especially with gorilla tag and having these kind of emergent social dynamics and the story built into the world and they've figured out something in terms of how to design immersive spaces that don't have like menus or other things that are putting other ideas from let's say like our user interactions that we may have from the phone or whatnot so just curious to hear a little bit about the first turning point for you to really start to see whether it's from immersive theater, whether it's from these performances or what really captured your imagination of this potential for story living?

[00:10:38.547] Joshua Rubin: Wow, well there's a lot in there I could unpack for the next few hours. I think, so early in VR, right, when I started experiencing, you know, the first time I experienced that sense of teleportation, that sense of I've gone to another place, that I haven't just, you know, I'm not just having, you know, memories of a game I played, I'm having memories of a place I've been. That was mind-blowing to me. And I immediately started thinking like, well, how are you going to tell story here? And really realizing like this is a brand new medium. This is a brand new medium that does not have a lexicon, a grammar of storytelling yet. And how lucky are we to get to live in a time when there is the possibility of creating a new medium together? There's a quote by Chris Melk that I always found really guiding. This was way back when we were all first starting at this, and I think he said something like, I'll probably mangle it, but something like, the ability to experience a story with another person, a story that we don't just watch, but that we live together inside of what is essentially an altered dream, will fundamentally change not just the way that we connect to story, but the way we connect to each other. And this has kind of been like a north star for me of where I think story is going, where I think... I want to go in telling stories is to create story worlds that surround you and make you not the audience, but make you the story. And so I love the phrase story living. It's really stuck with me. I think I probably heard it from Vicki first, although I think I remember I thought I had come up with it and then I wrote her an email saying, hey, you're using my phrase story living. She's like, no, actually, we came up with that when, you know, we were working with, you know, the BAFTA Institute on a research project. I was like, OK, OK, yeah, you probably did. But, you know, for me, like I've really defined my own understanding of what it means, like what I think story living is and what its potential is. And I kind of break it down into three things. I think it is when you as a player have radical agency when the world is hyper-reactive to you, where it yes-ands anything you want to do, any way you want to play, anyone you want to be, and also that the story is hyper-personalized to you, that the story knows you well enough to give you exactly the catharsis that you need to grow as a human being. this is you know more than just living in a world right this is more than just a simulacrum of a world this is really story that is hyper focused on you as the audience slash player to go on an adventure and to grow as a human being So the question is, how do you do that? Because that's, you know, that's a pretty tall order. And I feel like, you know, I've been spending a lot of my career investigating and playing with ways of doing that. And sort of I feel like as a player, when we play a game, we want agency, right? We want to be able to have the freedom to do what we want to do and to solve things the way we want to solve them with as few constraints by the designer as possible. in a story we want catharsis we want meaning and structure and theme and in a lot of ways catharsis and agency are completely at odds right how do you tell a story if you don't know what your character i.e the player is going to do But it is possible to bring those together to find a really good balance of catharsis and agency. And what I have found is that some of the best purveyors, the experts of immersive theater, over the past 50 years that I have been a student of have really solved this. And a lot of great video games too. And there's a whole language that exists in the history of immersive theater that is shared by a lot of what video games has done that I think we can go back to. And in that South by Talk, I kind of set out these 10 building blocks that I think we can use from the history of immersive theater and video games for this future concept of story living.

[00:15:14.471] Kent Bye: Yeah, I feel like that there's this paradox of, well, back in 2016, I was talking to Eric Darnell, and he was talking around this paradox. He said story is a time-based medium, and so you have to have the beats that are unfolding in a certain time structure, and that, you know, as soon as you give a player agency, then they're going to be thinking more about how do I express my will in this experience rather than following the beats of that structure, you know, you have agency and freedom to break out of that structure, but it's the structure that is able to contain the precise timing of the beats that's authored by the storyteller. So more from the cinematic tradition over into the video game tradition where Lebowitz and Klug, they've created a spectrum of different types of stories that I often refer to as I think about this where on the far end of the spectrum, there's like no agency and it's basically fully authored stories and you have the Aristotelian drama And then as you start to go further, further down into more and more agency, so then you might have light decisions that are then eventually converging back into the main story. So you have a way to maybe flavor your experience, but it's not meaningful agency that's actually changing the course of the story. And then maybe in the middle, you have the branching path narrative, which you have all these different branches that are authored, but it takes an incredible amount of effort from the authorial side to basically come out with all these potential possibilities that, as someone going through it, they may not even know all the work that you've done because they will only experience a fraction of that work. And so they're still, at the end of it, making choices but seeing a linear story that is after that. but the complexity of all those potential possibilities are lost on them, I find. And then you move into something that may be more along the facade model where you have story beats where you make choices, but then based upon the choices you make, you have the best story that's delivered to you at that moment, leaning more into the agency, but trying to blend and add the story element based upon how you progress. And then the furthest aspect is the open world where you can basically do whatever you want, and then that essentially becomes a sandbox And at that point you've lost all narrative structure and then it's difficult to have a sense of what the story is at all when you're focusing mostly on how do you express your will to the nth degree within the context of what at that point is more of an open world game or an open world sandbox. So yeah, I'd love to hear how do you resolve the tension between that spectrum?

[00:17:42.423] Joshua Rubin: Yeah, I mean, you put it out there really well. Those are definitely these gradations. And I really do believe that there is a way to have the radical agency of that open world video game and the authored story. It is. And there's all these tricks to it that I've sort of been cataloging and, you know... Look at, for example, Zelda as an open world game, an open world game that tells a story beautifully. And one of the ways they do that is with story magnets, with these things in the physical environment that lure you toward them is one way to think of story magnets. You know, in amusement parks, they talk about weenies. The weenies are the large architectural structures on the horizon that draw you toward them out of your curiosity, whether it's the Sleeping Beauty's castle or the Matterhorn or the Space Mountain. They ground a world thematically and they draw you toward them and give you a sense of space. In Zelda, they design in a way so that there's always something over the next horizon. And that they kind of know very intelligently as you go over the next horizon what the next thing is you're going to see that's going to draw your curiosity. And they allow you as an explorer to let your own curiosity guide you into the story. So it feels like you have incredible agency, but they also are guiding you. At the same time, they also yes and you. They give you tools that you can play with, and you can play with those tools in any way you want and combine them and make things. And that gives you an extraordinary sense of possibility. But then they also, by the limitations of those tools, create the rules of the world. And the rules of the world become the world building and the story that you're getting. And those rules are grounded in the history of the world. On the other side, another tool that I really love is I went to see one of the great pieces of immersive theater I've seen recently was a piece called The Mannequins by a company called Deadweight in London. It's a one audience member and two actors is the entire performance. And in it, You enter into a space and you talk with what appears to be a doctor, but everything becomes very, very surreal very quickly. And I don't want to give any of it away in case you ever get to experience of it. But what is amazing is that you have incredible agency to guide and shape the show through how you respond and where you take the show and what you expect it to be and what you want it to be. And there's this incredible sense of freedom. And at the same time, you are getting a full story. And, you know, there are, you know, different endings, but every ending is kind of yours and yours alone and dramatically, thematically linked to what you've done that came before. It never feels like it's gone off the rails. It always feels like it was meant to be. And so I got to talk to the creator, Jack Aldisert, about how he did this. And he talked about this idea that comes out of Stanislavski, which is, you know, Stanislavski is one of the great acting teachers from the 1960s, I believe, who talked about this idea of intentions and events and how in a great improv scene, if you as the actor have an intention, you know where the scene needs to go and you know what the next big event is that needs to eventually happen, then you can allow your dance partner in that scene to go wherever they want and get there however they want and slowly kind of guide them through your intention as an actor by what you want in that scene to guide that moment. And there's another idea that he talked about, which is cadenzas. And cadenzas comes from like, you know, classical music and quartets, and a cadenza is when, like in jazz, there can be a period of improv in between set beats. And so that ability to have structure and improv at the same time is a key component of this, that there can be always freedom for you as the audience player and a structure for where you're going, but also a structure that feeds back from what you are doing and the choices you're making. inability to bend the story and have it go in different directions. There's another idea that comes from my years at Telltale, where we were always using incredible smoke and mirrors to give you a sense that you could do anything while in a very altered story. And one of the most important ideas that came out of there was this idea that who you are and how you express yourself through the choices that you make as a character is going to shape what the story is but everybody's going to have a different version of that story and they're going to come out with not just different endings but you know different emotional experiences based on the choices they made and that one of our primary goals is to make sure that the theme of the story that you experience is not something that we know ahead of time, but that every ending that you can reach is going to be thematically true to the choices that you made along the way. That we're not telling you what the theme of the story is, you're finding your theme.

[00:23:21.297] Kent Bye: Yeah, that was a great recap of at least half of the points that you're making throughout the course of your talk. And, you know, one of the other things that I remember in your talk that I was really jealous and envious of is that you actually had a chance to do the Odyssey Works, which I came across them at one of the Noah Nelson and Noah Persinium had a gathering. And I think one of the people from Odyssey Works had a book that they gave me that they wrote about their whole process. But it sounds like that this is a type of immersive experience for one person where they will... basically do a whole deep dive about your life, talking to your friends and family, and then cultivate this community ritual that is very much tailored to you. And so I'm just curious, what is your input to something like Odyssey Works to have something that is, you know, that's something where it takes a lot of labor for people to do this building of a relationality, gathering of all this information. And then at what point are you adding what your intention might be or what you want? Is that a part of the equation? And then, yeah, just curious to hear a little bit more about this Odyssey Works experience you had, because it sounds like a pretty transformative type of immersive story that is specifically tailored to you.

[00:24:31.471] Joshua Rubin: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, talk about a hyper personalized story experience, immersive experience. I've obviously been a connoisseur of these experiences and sought them out. And this is, you know, kind of one of the most incredible experiences I've gotten to have as a theater experience. In terms of how my intention is expressed, I don't think it is because you really are an audience member experiencing it, but the intention has already been set in that you have allowed them access to your life. And what you're getting is a feedback about you in which they are giving you something specifically designed to give you the catharsis that you need in your life right now. I mean, I'll tell you a bit about the experience. So I had just moved to New York, upstate New York, with my family. And what they had picked up on was that I was in a place where I was feeling, you know, stuck in my writing and, you know, afraid of, you know, the changes I had made and what came next. And also obsessed with sci-fi and dystopias and, you know, post-apocalyptic worlds is, you know, sort of my comfort zone of what I like to read and write about. And so they created for me this experience where they drove me out to a cabin in the middle of the woods in the rain and left me there overnight with no phone, no wallet, no way to leave. And as I sat in this cabin with this incredible food they'd left out for me, I started to explore and see the various weird things that had been left in there and among them were all of these books and as I sat down to read I noticed it started on the second chapter and then I pulled another book and also the first chapter had been ripped out. And all of the books in the library of the first chapter had been ripped out. And that ended up becoming a theme that played out through the next day when they drove me into what became this post-apocalyptic world that they had built in the countryside of upstate New York. through all of these pieces of debris and people that I would meet along the way. They would drive me for hours to this farm stand. And we now lived in a time where the currency was stories and people traded stories for food and such. And we eventually ended up at this old artist colony where there were all of these artists who were struggling with their first chapters and how to write their first chapter. And the final evening of this multi-day experience was they gave me time to go to a cabin and write my first chapter. And then everyone met in this meditation hall and shared their first chapters that they had worked on over this period. there were all of these incredible experiences i mean that was kind of the framing device but one of them that i'll talk about that kind of blew me away was i was brought to the farmer's market in ithaca and given exactly 11 and 11 cents because they knew that the numbers 11 11 were very meaningful to me and told to go use it to buy a sacred object that was important to me, but not too important. And I found this incredible piece of carved wood and then they took me by bicycle to this waterfall where I found about 50 people who were all in the middle of a dance. And they invited me to join them. And it was a ritualized dance where they all were choreographed and I had to figure it out as if I was entering into this society of, you know, cultists, you know, performing this ritual. And the ritual was they would do a series of hand movements. They would go to each person, we would do a dance to each other, do this series of hand movements, and then gift each other their small, important object that they had brought with them. And you could say yes or no by the move of your hand and then move to the next person. It was very simple and very beautiful. And I couldn't believe they had gotten 50 people to show up for this thing. But this feeling of stepping into like a story that was already ongoing. that I was just a player in, a part of, was very existential and very beautiful. And also the realizing that I could not let go of this piece of wood, that even though I traded it around from person to person, I eventually made sure I found my way back to the person who had it last and took it back because I was very good at finding something sacred and not very good at letting it go. That was a very good lesson. So that's very personal. But what was amazing about it was this experience of really getting to be the center of something this big was kind of terrifying and extremely beautiful and something that I would wish for everybody. But how would you do this for everybody? Part of the design seems to be that a group of artists decide that this is a practice where they're going to selflessly make theater for one person who they spend the time getting to know their life. Well, we can't do that for everybody. We can't scale that, as you say. But we have AI coming and we have AI coming in a way that can get to know us so deeply and so personally in a way that is terrifying but is also beautiful. And I've already had moments with ChatGPT where I have asked it to give me feedback on who it thinks I am and how I could be a better person and how I could grow, questions like this. And I swear I've never felt so seen. Like it is shocking and beautiful. And I think when we talk about personalization of story and what AI could be in its best form to allow us to be really seen and then to be a co-creator of a story with us to guide us into a story that can give us to know us those little things that we're going to need to grow as people would be amazing.

[00:31:03.260] Kent Bye: Yeah, I think when I first got into the XR space, I had seen Sleep No More, and eventually I saw Then She Fell, but I saw Sleep No More back in 2011, like three years before I got into VR. I just happened to be in New York City on a work trip, and my coworkers went, and I went, and my mind was absolutely completely blown open, and I... I went home and I stayed up all night writing everything that I could remember. It was basically one of those things where I had one night to see it. I wasn't going to be able to see it again. And so I did a little bit of researching online, but not too much because I didn't want to spoil things. So I was trying to say how many of these different characters did I see and record everything that I could remember. And I wrote a big long blog post, but it was really an impact on me to see this level of immersion that was probably one of my first real tastes of an immersive story that I felt like I was really able to be transported into another world. Really felt like walking through a dream in a lot of ways because there's no language and you have to interpret all the movements and it feels like very much a dream logic type of experience. And so during the early parts of thinking around immersive storytelling, I think I was thinking a lot more around like AI is going to replace these actors because we can't scale up doing something like Sigma more. I think as time has gone on, as the industry has continued to develop, I think I've grown more of an appreciation of how much humans can react to the humanness of it. But there's also like being ensouled by engaging with other humans in these different magic circles and contrived contexts. I think I've become less personally interested in how can we recreate some of these very human stories with AI because I feel like there's a certain amount of the insolvent that is being automated out that I just am more hesitant or more skeptical and also just the more I read around AI and all the ethical issues around AI and all the ways in which AI as a tool of consolidating wealth and power and who is benefiting from that automation and who is losing out. And I think in this area of story living, I think, is an interesting intersection because I do think there are some roles to have AI agents because we couldn't have something like what you experienced with Odysseyworks scale up for everyone. Or if we did, we would have a completely different society, which maybe we should think about living into as another utopic dream space of the future where this type of communal art is something that we do for each other more often. So I'm more inspired by that vision of the future rather than offloading that onto AI. So I don't know how you start to navigate how much is the human being lost when we offload some of these things that we have had with actors and immersive theater actors into AI.

[00:33:42.222] Joshua Rubin: So I am right there on that push pull with you. I mean, you know, on one hand, like AI is magic, right? It is. I mean, we are living in a time of magic dawning on Earth, things we never could have imagined. Well, Of course, as in any great story, that amazing magic that comes into the world is going to come with incredible costs. Of course it is, that it's going to destroy our environment and turn us into what we don't know. It is wild and weird and terrifying, but it's magic. And I think really focusing on the magic is something we don't want to lose sight of as we negotiate what we want with AI. At the same time, I believe strongly in the importance of human connection. And we are also very soon going to be completely surrounded by AI slop everywhere all the time. And we are going to crave human connection like never before. I imagine in the same way that the automation of the 60s brought us McDonald's and fast food and everybody wanted that. The world quickly turned against that and farmed a table and Whole Foods suddenly became, no, we want real things again. I think that we're going to want real human connection. And so I think that's where in the world of story living, location-based VR really excites me. And I love the idea of location-based VR with live actors. With live actors who are there with you, able to yes and you, to really bring to life the world that you're co-creating together. I think that the AI goes one direction and live actors go the other. The thing about scaling with live actors, though, is it's not something that you can distribute. But I think the model is really Broadway, right? The model is, no, this is a premium experience that people will come for. That if you create a really premium, unique, location-based VR experience that gives you a truly interactive adventure that you live with your friends, that is something that is going to be potentially really transformational of what story is.

[00:36:08.945] Kent Bye: yeah yeah i do want to push back a little bit on ai as magic just because i think if you trace back to everything that is magic about ai you can trace it back to human and human intelligence and also ai as a term was made up in 1956 by john mccarthy as a part of the dartmouth conference on artificial intelligence and before it was some weird automata like more of a neutral term but as soon as he called it artificial intelligence it became a marketing term so that we project onto that term artificial intelligence what we know of what intelligence is but yet actually it's never been well defined as to what AI technology is and that everything that's magic around AI is this projection from our mind around what intelligence is and that you can just break down AI into the component parts of what it's actually doing like Emily Embender and Alex Hanna and their book called the AI icon, which they're trying to deconstruct different aspects of the AI hype. And part of the AI hype is to believe that AI is magic because it is actually just these functional things that are, you know, image diffusion or synthetic text extruding machines. And so but all of this is based upon human data. and that AI wouldn't be anything without humans. And so I feel like there's a trap here that part of this moment is to deconstruct the illusion and disillusionment that we have around these technologies and that there's a certain amount of hype, AI hype, and that by believing that AI has magic is sort of believing into this AI hype that allows us to collapse the complexity of what it means to be human. and that collapse, we think that it is a good idea to start to replace human and human labor and the magic of human intelligence with these things that we're projecting onto it way more magic than is actually there. So I'm actually more of a contrarian around AI and want to be hesitant to how much we're buying into the AI hype. Because there is some stuff that has been magical around, say, image generation and mashing things together, but all of that is coming from human-captured data that wouldn't exist without the input from humans. And without the human data, AI has nothing.

[00:38:16.861] Joshua Rubin: If you think of AI as an extension of humanity, not as a different thing, Right. But in the same way that we all grow by absorbing everything around us and creating something new from it, that's what this new species is doing. Right.

[00:38:33.031] Kent Bye: I mean, even to call it a species, it's like it's anthropomorphizing it. So I think artificial intelligence as a name, I don't know what I decided to call it separately, but Emily M. Bender and Alexana, they'll call it like mathy maths or other with scare quotes. They'll call it AI because it's what other people are saying. But I think it's part of the moment right now of this factionalization of people who are the true believers of AI and the people who are kind of abolitionists or skeptics or like really trying to send all of AI into the burning sun. So I feel like I want to have a foot in both possibilities spaces, but also be cautious around, you know, like I go back and listen to old interviews that I did around the very beginning of this getting into immersive stories and how much I'm very quickly thinking around, well, let's offload this into AI. But then now with all the context of how AI is a tool of consolidating power and wealth, like who's really benefiting from that? And I think in the context of story, the audience member can benefit from that type of automation. But that in so many other instances, it feels like who's benefiting is just consolidating that wealth and power into big companies and corporations. So anyway, it's something that I'm still wrestling with. And I think in this intersection of AI and storytelling, it's something that I'm... obviously still trying to wrestle with and negotiate what's a good context, what's bad context. Part of it is, like you said, being on as an experiential journalist, there have been some experiences that will completely offload the narrative and the resolution of a narrative. to having a open-ended, aimless discussion with ChatGPT, which then is just complete AI slop. It's like this totally ruins the experience of what you were trying to create with your humanness, and every time it would go into more of the uncrafted aspects of a large language model, then I'm just exasperated at that point of being, oh God, now I'm just chatting with ChatGPT as a part of your near experience. I could do this at any moment, and I think this is terrible art at this point. I think that's part of the context of my experience of trying to really rein in the AI so that you're taking so much out of the probabilistic next word out and then really trying to author it in a way that makes it feel like a meaningful experience. And I know that you had said that part of what you were saying is that you actually need to break down the AI into these two component parts of both the intention and the events. And that one potential solution is to have the AIs that are actually cooperating or in conversation with each other so that you could have some of these more emergent story dynamics that are having the different parts of how actors have intentions and events and then being offloaded into AIs.

[00:41:15.427] Joshua Rubin: Yeah, that was one idea that I had talked about, this idea of having kind of like a id and a superego, two different AIs, and that's something that I see AI companies already doing, where one is kind of creating the information and the other is then looking at the information before it's fed and saying, well, is this accurate, is this true? In a story context, it would be like, you know, one is kind of knows the intention and the other knows the goal and, you know, or one is creating, you know, the dialog in response or maybe another knows, you know, the player and has that history in their mind and that these different AIs are working together to create a character. That's really interesting. I hear everything you're saying about AI and, you know, I am I am just fascinated by AI. And I am terrified by AI. And I am so excited to be living in a time where the world is changing so quickly. The same way I was excited about the birth of VR and I was like, this is a brand new medium that we get to experience. I mean, we are at the birth of a medium of a technology that is going to change the world. in ways we cannot imagine. And I find that thrilling to get to be alive for. I think it could go terribly wrong. There is almost no doubt that there are going to be terrible, horrible consequences from what we are making. or what we are watching being made, whether we like it or not. And I also think they're going to be wonderful, breathtaking miracles in our world that we couldn't have imagined. And I think both those things will be true. And, you know, in terms of AI and story, I mean, I do think there will be endless AI slop And then there will be the ability to really teach an AI all of the great rules of story and character and immersive theater and video games. Like there's so much that we know that is possible to impart. And if we can impart it to, you know, if we can really train an AI well, it can do wonders.

[00:43:29.807] Kent Bye: Yeah, there's a quote that I often come back to from Robert McKee where he talks around how story is around characters that are making choices and it's from those choices that you get to see parts of the character being revealed. And I feel like that this focus on catharsis and having some sort of cathartic experience for the user there is this sense of like well how do you know what is the block in someone's life it seems like this odyssey works experience that you had where they're able to really investigate like what is the deepest catharsis that you need and then how do you architect a series of ways that you can engage into this ritual and then allow you to immerse yourself into this world and and also give you the ability to make these choices and to actually take action and that Robert McKee talks around these moments of pressure, so intensity around a certain choice and that the more of the stress or intensity of that choice, the more of your essential character that's being revealed through that. So as you're thinking around story living and creating these contrived moments of catharsis, How are you starting to really lay out how to construct some of these different moments that you experience? It's almost like an abstraction of all the different variety of different types of things that people could be going through. It could be a very specific type of thing that will really resonate with someone at a certain moment in time, but not with others because maybe it's not the most crucial thing. So yeah, I'm just curious. this dilemma of trying to really do something that's not just like immersive and experiential, but really transformative, I think is the core is like moving from experiential to transformative experiences is to really figure out what is the thing that's really going to catalyze that transformation and that creating these contexts or rituals or worlds that come up with some of the edge of whatever transformative experiences that you may have. So, yeah. How do you create transformation on demand? I guess it's a question.

[00:45:24.021] Joshua Rubin: That's a damn good question. You know, obviously, the way that Odyssey works and, you know, I should credit, you know, that's Abraham Berkson and Aidan LaRue are the creators of that theatrical troupe that kind of developed this idea of why make a theater piece for, you know, thousands of people with the hopes that one or two of them have a catharsis connecting with what you intended to say. Wouldn't it make so much more sense to choose one person, understand what the catharsis is they need and give that to them directly? And the way that they do that is very labor intensive. And it is an act of love. It really is. They say, we believe that we fall in love with the subject of our pieces in order to give them the performance they need. And they talk to everybody in your life that you're willing to let them talk to. They watch your favorite movies and listen to your favorite music. And how do you do that for everyone? Well, you can't. You can't. So the best that you can do is, you know, one thing that, you know, we used to talk about at Telltale is this idea of designing different paths for different kinds of players and that based on the kinds of choices that you make, we will learn about you and we'll learn what kind of person you are. Are you risk averse? Are you aggressive? Are you going to go for the joke or are you going to stand back? And that as we learn about you, we can trigger a certain set of experiences that will only happen if you're the kind of person that we know this is going to affect and that it's going to challenge you and challenge exactly the thing that maybe you're averse to and that then if you can overcome these challenges you will reach a certain kind of thematic catharsis that we will have given just to you because that was something we knew that you would be challenged by and grow from and if you can create enough of these kinds of paths then you can at least have a lot of general movements to catharsis for different kinds of people that the structure of the experience itself can guide you into the path that will lead you where you need to go. I will say these were only discussions at Telltale. We never actually managed to do this, but it stuck in my head and became very much part of the lexicon of ideas that I've been playing with. but these are very guided experiences, right? Telltale style games, choose your own adventure games are always limited by what the designer can imagine ahead of time that you might want to experience, that you might do. What really excites me about having location based experiences with live actors, which is what I'm excited about building now, is that like Dungeons and Dragons, right, they can give you room for a kind of radical agency. And if these are trained actors who really understand intentions and events and cadenzas and ways to guide the story and guide each player toward different directions based on the clues that they're getting from you, then you can really have an ability to improv and yes and, and really feed people back what it is that they need. It's hard and it requires an incredible sense of skill and incredible art. But I think we can begin to, you know, as we talk about these ideas and getting to talk them out with you, you know, lay out these building blocks and these processes and these tricks that all together can make something really incredible when done right.

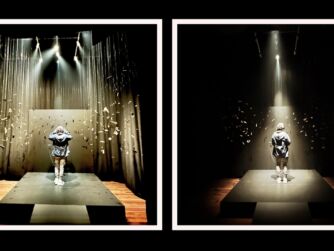

[00:49:20.205] Kent Bye: Yeah. And there's a couple of other immersive theater pieces that you had mentioned. One is Then She Fell and another is You, Me, Bum Bum Train. And so I haven't seen the You, Me, Bum Bum Train. It looks incredible. Then She Fell, I did actually have a chance to see when I was in New York and had heard about it from Noah Nelson and Noah Prasenium. And that was an incredible piece because it was like what Noah described as like this clockwork architecture where you You know, in Sleep No More, there was a potential for you to have a one-on-one interaction. And I was lucky enough in my one time that I went, I had maybe one or maybe one and a half, like, one-on-one encounter, which was really quite amazing. You know, but then She Fell is basically orchestrated so that you have, like, one-on-one encounters, like, continuously through, like, these 15 different actors that you have that you're going through. And because there's 15 actors, you're all going through, like,

[00:50:08.979] Joshua Rubin: the same path in audience members right so it's a limited group of people and you each go off on your own path and going from room to room to room like clockwork like you said and i had that same experience too like i had you know my sleep no more experience where you have almost no agency except you know where you wander and then you have that one-on-one experience where you're suddenly being seen and your mask comes off and you're interacting and i remember being like this is magical i want more of this And then I got to Then She Fell, which was all one-on-one experiences. And it was kind of like this migration. So you and me bum-bum train?

[00:50:45.026] Kent Bye: So just to follow on with Then She Fell is that there was something around the gaze, the eye gaze, the eye contact that I feel like... there was something around the humanness of that encounter of being in the presence of another human and having that attention from another human that I think would not translate as well into a virtual experience or a virtual actor or an AI actor. And I think that with Yumi Bum Bum Train, again, I haven't done it, but it sounds like part of it is a spectacle of going through a series of different contrived scenes that you're thrown into the middle of from one context to the next and then but in each of those contexts there's like a group of people that are co-constructing this reality that you are in relation to and you as an audience member are expected to kind of like improv through each of these different high pressure situations one after the other is sort of my impression of it but that again if that were a AI experience and these were all AI agents then I think it would feel different. I don't know if it would translate as well, because there's something around the humanness of being around with other people and the fact that it's so awe-inspiring that there would actually be this many people that would be willing to do this type of performance. And so there's something around both the then she fell and the you me bum bum train that feels like there's something around the humanness of those actors and the spectacle. So just curious to hear some of your thoughts of the other types of lessons that you've taken from those different types of immersive experiences.

[00:52:15.635] Joshua Rubin: I absolutely agree with you that the human connection is incredible and essential to this kind of experience. I have also had enough experiences that mix VR with live actors to know that that is also incredible without direct eye contact with a person because touch is so profound. Dana Tannehill, I think I got her name right, did a piece called Draw Me Close. Did you experience...

[00:52:44.011] Kent Bye: I saw like an early version of it at the world premiere at Tribeca Film Festival. And I did an interview with her as well as David Oppenheim. It's one of my unpublished interviews with David Oppenheim talking about Draw Me Close. But yeah, I saw it in Tribeca and, you know, in an experience where you are the child of a mother who is dying from cancer and that you have an opportunity to embrace her as you have this encounter with her through being co-located in the same room, but she's represented in this animated world, but there's a blending and blurring of those realities of the animation when you embrace and hug there at the end. But yeah, it's a really powerful piece.

[00:53:19.684] Joshua Rubin: And I think it's exactly that, right? The fact that you're not seeing a human, right? You're seeing a cartoon. You're in a fantasy world or a memory or a sketch. And yet that sketch has reality. She hugs you. She tucks you into bed. She plays... sitting on the floor with you, both sitting on the floor playing a game. And that sense of like that mix of like physical reality and being in a fantasy world is what is so magical beyond just eye contact with another human, right? It's the physicality mixed with fantasy that's transformational. There's a moment I love in Chained by Justin Denton and Madison Wells Media produced it. And I remember this moment where you are sitting in a room, in a physical room before you put the goggles on that is set dressed. You put the goggles on and you're still sitting at the same desk, still looking at the same mirror, except now in the mirror you see a ghostly form and a hand reaches through the mirror for you. And you reach out and you take the hand. And suddenly, while you have had the goggles on, the desk and the mirror and the wall are gone. And you get yanked through the virtual mirror into this other world by this physical hand. And that was mind blowing. That was fantastic. That way of mixing the virtual and the physical. And so I love I love that. Yeah.

[00:54:46.912] Kent Bye: So I think in this combination of stories where you're receiving an author narrative, you're mostly going through this time-based experience of a story that is being constructed for you with a lot of the structure. But it feels like there's a lot of the breaking down of that structure that allows you to really interrogate and find this place of curiosity, exploration, play. I think of it as kind of like the water element where you're receiving the story and the fire element where you're really engaging, exploring, playing, chasing your curiosity, expressing your will. So yeah, just curious to hear some of your thoughts on why you think that elements of play and interaction, participation is so important for the future of storytelling.

[00:55:33.570] Joshua Rubin: Yeah, I mean, so I think a lot about like how when we go into immersive experiences where we're not just an audience, we have to be vulnerable. We have to open ourselves up. We have to engage. We have to be active. And that can be very intimidating. right for a lot of us and what we need is we need a permission to play we need a you know in LARPing they talk about the alibi LARPing being live-action role-playing right and how you need to be given the alibi and to play the same way that the mood and the setting what everyone else is doing around you creates that alibi in the same way that when you go to a dance hall and the lights are dark and the music is playing you're given an alibi to dance to be free to let go how do we give people that freedom to let go that ability to step out of their usual routines and do something else and be something else It's hard to do that. It's hard to do that around other people. And if we can get inside that magic circle where everyone is doing it and where we're all kind of in that together and create a permission space for that, that is a fundamentally beneficial thing to do for humanity. because we need to play. You know, play is a fundamental human need. There is the Institute of Play put out, is a real institute that put out a paper last year that really talked about how we have a deficit of play the way that we have a deficit of sleep in this country. And that play is as important as sleep and that people who play more are more creative. They work better with other people. And people who don't play really lack these same aspects. So the more that we can allow people to play and give them permission to step out and become something other is a beautiful thing that we do. And it's a responsibility we have as immersive makers to give people that.

[00:57:35.615] Kent Bye: Yeah, and because you are with another Axiom, Girl Attack being, you know, one of the most popular independently produced games out there, you know, Beat Saber is probably way up there too, but in terms of having like $100 million of revenue that they've had over however long they've been out now, you know, moving on to Orion Drift, they're trying to create this open world that you're seamlessly going in between these different things where there is like an esports element where there's a lot of focus on the play. And so when you look at something that has a center of gravity of play as why people are there, then how do you add these other story elements? Just curious to hear what that process has been like for you to take something that is at the core, something that is rooted in the gameplay, and then add these other story living or the story of Orion Drift.

[00:58:21.596] Joshua Rubin: Sure. Yeah. Well, I mean, talk about a challenge as a writer and a creator, right? Because Orion Drift is not a story first game at all. It is a community space. It is a play space. It is a clubhouse. It is a team sport. But when they came to me, they basically said, okay, we have this space where you are robots in space, but why are we robots? And why are we in space? And where are we going? And like all of these like fundamental questions they'd been wrestling with for like a couple of years already. And, you know, and they kind of gave that to me as a task, like give us not just the what we do, but the why we do it. Why are we here? Where are we going? And then it became a question of once I started developing this whole story world around the play space, then it was how do you tell this story? How do you tell the story through play? And then it really came back to this idea of story magnets, this idea of creating curiosities that draw you. Because one thing I know about humanity is we love to explore. We love to find things ourselves. We love to go through the door that is cracked open that we're not supposed to go through. And we want to go into that tunnel and see what's at the other end. That's why Meow Wolf works so beautifully, because we get to explore that world for ourselves and find the story for ourselves. And so that's how we're telling the story in Orion Drift, through discovery and exploration and curiosity. And then through community, through building the story from clues together. What does this all mean? And what are these mysteries? And what does it point at? So it's creating a story world and then creating a way of telling the story through play. And there is this core idea that, in the story, that really ties into this, which is that the robots have these balls in their chests. And this was just, you know, a design element, right? If you have a ball with you, you could always, you know, throw it to a friend and play and start a ball game wherever you are. So they named it the heart balls. They didn't know why, you know, because it was in your chest. You reach for your chest and you pull it out. So I ended up creating this whole mythology that these were these like quantum balls that were, you know, designed for these sports droids to play with. That what they didn't know when they designed this is that through play with each other, the robots began to connect and bond. And that it was the sharing of their heart balls, which the robots themselves named it that, that it was through play that their intelligence and their sentience developed.

[01:00:55.874] Kent Bye: And so, yeah, I guess as we start to wrap up, I'd love to hear what you think the ultimate potential of immersive storytelling and story living might be and what it might be able to enable.

[01:01:06.050] Joshua Rubin: Having listened to so many of your podcasts, you would think I would have prepared for this question better. But I do actually have a manifesto of immersive story that I have been building and working on and what I think immersive story can be in the future, where it should be going, what I think we're on the frontier of. And it really is just six points that this is what we want story to be. We want radical agency, not just activity in immersive experiences. We want transformational experiences. We want permission to play. We want to believe that it's real. We want to feel connected to other human beings through our stories. And we want to be the story, not just the audience. so this to me is kind of the guiding posts for me of what i am trying to build what i believe we can build what i want to experience as an audience member and player and i use those words kind of interchangeably but as player and audience merges you know as we go into this future world where video games and movies and all of it kind of come together into some kind of hybrid experience that we cannot predict yet I am so excited to be in this period of the world, not in terms of so much of the horrible things that are going on, but in terms of the potential for story and technology to transform who we are and how we connect to each other.

[01:02:48.735] Kent Bye: Beautiful. Thank you for that very condensed manifesto. I feel honored that you're sharing that here. Is there anything else that's left unsaid that you'd like to say to the broader immersive community?

[01:03:01.627] Joshua Rubin: We all feel like we're faking it. We all feel like we don't really know what we're doing, and that's okay. I like to sound smart, but the truth is I have no idea what I'm doing either. And I think it's great to all be human together, muddling through this experience together, trying our best to make something, and each of us are a part of it. And as we do our little bit to add to this tapestry, we will create something amazing for each other bit by bit.

[01:03:32.648] Kent Bye: Awesome. I really enjoyed having a chance to sit down and unpack a lot of your ideas and immersive storytelling and all your career of being a professional in this area. I feel like I'm an engineer who's trying to figure out the patterns of these things. And I come at it from looking at the affordances of the medium first and how all these things are coming together. But I can tell that you're coming at it from a story first and as a storyteller and someone who's a writer and who's helping actually craft these stories. There's a lot of really deep insights you have in terms of all these other things that have... have not been on my radar in terms of how you're articulating all these other components and ways to kind of resolve these intractable polarizations of these two things that feel like they're in commensurate almost like mutually exclusive like agency and catharsis and having a way that you're turning it into a spatial context and through that they're become more of two sides of the same coin where they're mutually implicative where they are implying each other where in order to have these different moments you are mixing and mashing all these things and unique ways and i feel like in the context of immersive and these interactive and participatory experiences that we're going to be continuing to define all these emerging patterns that we're still discovering in terms of the the future of storytelling and so yeah just really appreciated all your insights and it's a real pleasure to get a chance to to pick your brain and to see how you're weaving all these insights together so thanks so much for joining me here on the podcast to help break it all down

[01:04:55.202] Joshua Rubin: That was so beautifully put together too. Thank you so much. I think everything that you're adding to, as you said, the tapestry of the history of VR is really important too. So it's a pleasure to get to be a small part of it.

[01:05:09.790] Kent Bye: Thanks again for listening to this episode of the Voices of VR podcast. And if you enjoy the podcast, then please do spread the word, tell your friends, and consider becoming a member of the Patreon. This is a supported podcast, and so I do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring this coverage. So you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. Thanks for listening.