Here’s my interview with Brenda Laurel, Board of Virtual World Society, VR Artist, Theorist, Writer, Speaker, Designer, author of five books including Computers as Theatre, that was conducted on Wednesday, May 29, 2019 at Augmented World Expo in Santa Clara, CA. See more context in the rough transcript below.

This is a listener-supported podcast through the Voices of VR Patreon.

Music: Fatality

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Rough Transcript

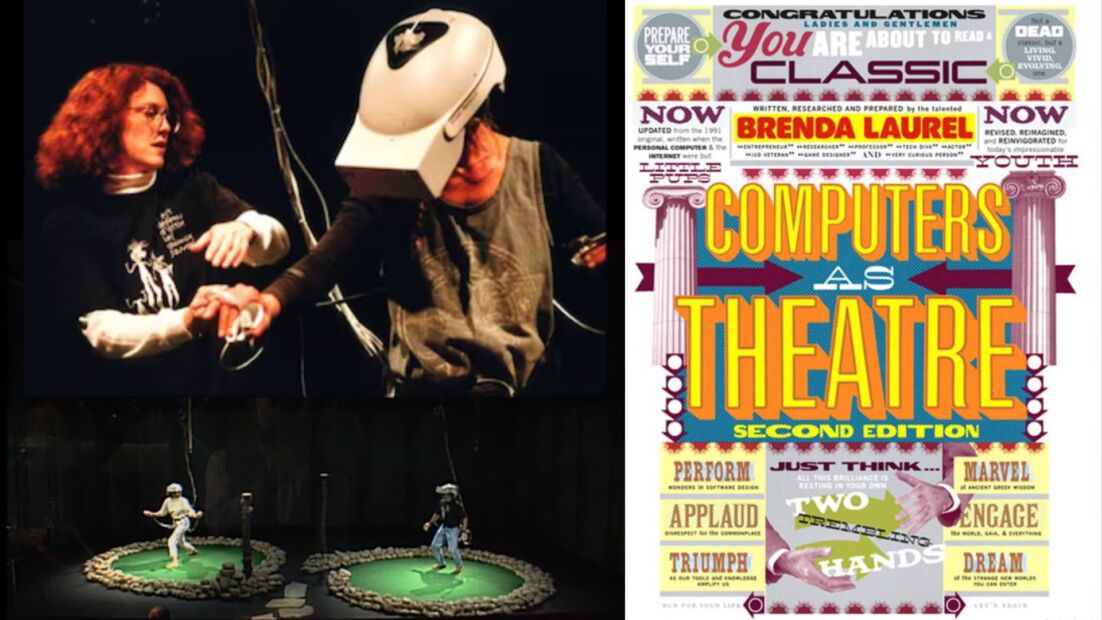

[00:00:05.458] Kent Bye: The Voices of VR podcast. Hello, my name is Kent Bye, and welcome to the Voices of VR podcast. It's a podcast that looks at the structures and forms of immersive storytelling and the future of spatial computing. You can support the podcast at patreon.com slash voicesofvr. So continuing my series of AWE past and present, today's interview is with Brenda Laurel, who's a VR artist who was making art with VR back in the 90s. And she also is a writer and a theorist, and she's coming originally of video games, working in since the mid-70s. Working on a number of different video game projects and then getting into this intersection of how do you start to interact with media and art with virtual reality as you have an embodiment. And so a lot of work was exploring that. And also she wrote a book called Computers as Theater, which is really quite provocative idea exploring this intersection of reality. narrative theories interfacing with virtual reality and embodiment participation and that's certainly a trend that has continued to play out in terms of the interface between virtual reality pulling in lots of different theatrical elements in the previous interview that i did with deirdre lyons and the next interview that i'm going to be doing with joshua rubin where he's pulling in lots of insights from immersive theater these ideas of story living and participation narrative and this this fundamental tension between like the narrative design, which is typically like you're receiving a story and the interactivity and participation, which is more of architectures for open worlds and creating opportunities for you to participate, but do it meaningfully. And so how do you start to blend these two realms of the narrative, but also the conceits of game design and seamlessly meld those together? It's one of the persistent open questions when it comes at the intersection of the future of immersive entertainment and immersive storytelling. Brenda also talks a bit about these larger issues of ecology and the ways that she's thinking around how virtual reality as a medium can help us become into more relationship to the world around us, which I think is a consistent theme throughout this conversation. And also she was at AWE in 2019 talking about ethics. 2019 actually ended up being quite an epic year. Actually, 2018 and 2019, I think I went to like 15 to 20 different events on each of those years. So on average, like once every three weeks, I was going to all these different events. And throughout 2019, the thing that I was really focused on quite a lot was ethics and leading up to my XR ethics manifesto that I did at the virtual reality strategy conference later in that November of 2019. But a lot of the conversations that are leading up to that for both 2018 and 2019 are thinking around these bigger and larger ethical questions. Yeah. So we're covering all that and more on today's episode of the Voices of VR podcast. So this interview with Brenda happened on Wednesday, May 29th, 2019 at Augmented World Expo in Santa Clara, California. So with that, let's go ahead and dive right in.

[00:02:53.780] Brenda Laurel: My name is Brenda Laurel. I work on the board of the Virtual World Society. I did my first big VR piece in 1993 at the Banff Center for the Arts. I'm a theorist. I do a lot of writing, speaking, and I'm a designer.

[00:03:13.529] Kent Bye: And you also wrote a book about spatial computing. Maybe you could talk a little about that.

[00:03:18.644] Brenda Laurel: Well, I've written five books. Which one are you thinking of?

[00:03:20.825] Kent Bye: I'm thinking about the one about theater, Computing as Theater. Yeah.

[00:03:23.867] Brenda Laurel: Yeah, Computers as Theater was actually my first book. And I rewrote it 20 years later because so much had changed. You know, I had written the book before the internet happened. it was based on my phd most people's first books are where i was really trying to visualize using artificial intelligence in an immersive environment to help generate good next choices or consequences for people's actions and i based the guts of it on aristotle's poetics Although you could build a similar system, say, using Brecht's theories or other approaches to drama.

[00:04:06.130] Kent Bye: Do you have a theater background?

[00:04:08.952] Brenda Laurel: Yes, I have an MFA in acting and directing and a PhD in drama theory and crit.

[00:04:15.066] Kent Bye: Well, it seems like that there's a lot of spatial computing and storytelling, at least, where we're seeing a lot of the blending of immersive theater. And it sounds like that you've been on the forefront of this overlap for a long time. And I kind of see like virtual reality creators as almost like architects where they have to pull in lots of different dimensions. And I feel like one unique component that architects are not looking at are this element of storytelling and theater. But it seems like using embodiment and moving bodies through space is a key part. of theater and that seems to be coming through computing. And so I'm just curious how, you know, what other different types of connections you saw between the theater and the future of spatial computing?

[00:04:55.182] Brenda Laurel: Well, that's interesting. Well, I think I've been obsessed with the notion of interactivity since I started in 1976 in the game industry. Because in those days we didn't really know what it was, in a funny way. You could turn your TV on with a remote controller, but the notion of actually interacting with a digital device was mysterious. As a theater person, I had been acting in and directing improvisational work, mansion staging work, where the audience's input could influence the behaviors of the actors. And those were the days in the theater when that kind of theater was going on. Dionysus in 69, Hare, interacting with audiences in a kind of risky way for actors. So... I think the connection for me with theater started with the notion of interactivity and how, as a skilled improv artist or a director of interactive theater, you can't simply tell a story. You have to predispose people by the way you arrange the space and the actors to make dramatically interesting choices. And so the story really is what I tell myself happened after I've had an encounter in a virtual world. It shouldn't be something that I'm yoked with by the creator. That's a different medium.

[00:06:29.144] Kent Bye: Yeah. Maybe you could connect the dots a little bit of getting interested in interactive gaming and having a background and a degree in theater. And then how did virtual reality start to come into picture for you?

[00:06:41.591] Brenda Laurel: It started to come into the picture for me from my imagination and from my experience as an actor. Because when you're an actor, either in a play or in an improv, in a way you're doing virtual reality, right? And so, you know, I thought, well, gosh, gee whiz, you know, why can't we expand this a little bit and use computation to build environments and maybe even characters so that everybody might be able to have that glorious experience of being an actor, of actually getting immersed in a play. I think that was part of the stimulus for me. And then later in 1986, I guess, I saw my first VR, still bright green vector graphics, at NASA Ames Research Lab, where they were using it to train astronauts. So by the time I got to designing and producing my first piece, it was really a design statement saying that this medium is good for more than training you know and i think it was successful in that regard so that's what got me started what was your first piece placeholder it was 1993 three environments captured in different ways from the natural world around banff canada and it was performative as well so there was a set people could watch you what you were seeing on the screen, but they could also watch your body as you were interacting in the VR space to participants. When you came into the experience, you were in a cave, how platonic, and there are petroglyphic animals talking to you and trying to entice you. And if you put your head in one, you became the animal. So if you were a crow, then you could fly. If you were a snake pit viper, you could see into the infrared So in these smart costumes, people had to experience embodiment in a way, because they were in different bodies. These were the days when people would say, especially men, that VR was an out-of-body experience, where women were saying, I'm taking my sensorium into this new place. This is anecdotal, but I heard enough of it that I think it was probably true. So forcing people to enter the bodies of animals was a way to bring their attention to the fact that they were embodied in the space. So they could play around, improvise, using magic portals, go from one environment to the next. One of the things we discovered, for example, that I think today's VR developers still don't quite get is that jump cuts don't work in VR. So the point and teleport stuff is really a bummer for your sense of flow. What we learned was to get from one place to another, it took people about two seconds of darkness. And the way we transitioned them was to start feeding audio from the place they were going to as they came through the portal. So it was a smoother transition. That's one of many ways to get around in VR that I think today's practitioners need to work with more.

[00:09:48.826] Kent Bye: And so since 1993, did you remain involved in the immersive VR industry? Or what were you doing in terms of up until the modern resurgence of either augmented or virtual reality?

[00:10:00.757] Brenda Laurel: I was mostly teaching. I founded the graduate media design program at Art Center College of Design in 2000, chaired that program until 2006, founded the graduate design program, which was a transdisciplinary program at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, and taught there for six years. And then I went to UC Santa Cruz for a few years in their game program. So touching on VR and all those environments, but more as a teacher, you know and a critic a practitioner of critique right so I early on became enamored of the work of Henry Jenkins who talks a lot about transdisciplinarity in design and I think XR goes alongside graphic design industrial design animation these things are all connected more and more as time goes by we see them traveling in little flocks and those skills needed in interdisciplinary teams to really make good experiences.

[00:11:05.387] Kent Bye: Yeah, I tend to think of it as the process of experiential design, creating experiences for people. But the transdisciplinary design frameworks, there's many different disciplines and domains that have their own philosophies of design and different frameworks. And so I'm just curious, when you look at the theoretical landscape, if there's any particular design framework or theorists that you look to in terms of making sense for designing for a direct embodied experience within spatial computing.

[00:11:36.294] Brenda Laurel: I'm going to say something strange. I think the best stuff I've seen is Meow Wolf, and it's live. And I would love to see VR that rich. I think we've come a long way. I think the most robust work is work that provides the greatest degree of choice and agency for the participant. So you get beautiful things like tree or giant, you know those people, where it's gorgeous and you do feel embodied as that tree and yet there's this inevitable outcome that there's nothing you can do about. So that's crappy on a couple of levels. One is that you don't have agency. Two is that bumming people out has shown itself to be a poor approach to getting people's attention on climate change. So adding an element of choice and visualizing the Gaian ecology that's going on in that piece better and more fully would make it a better piece. So the skills that are there are beautiful, right? Great animation, great capture, wonderful use of scale. I mean, that's one of the things I love about tree. The piece that's missing is the hardest piece. I think it's demonstrably the hardest because we get 360 cinema and we call it VR. We get actual plotting, storytelling, and we call it VR, where the outcome is a given. The hard part is making it more like a renaissance fair, where you put things in the kinds of interactions that can happen predispose you to make your own story as you move through the world with the fullest degree of agency possible that's the ideal so i think that for me it is and i think that the ability of people to design in that way is the thing that most needs attention

[00:13:41.004] Kent Bye: Yeah, I kind of see that there's these different equivalence classes of presence, whether it's having a mental and social presence. So if you're solving a puzzle or mental friction or using the language of abstraction to be able to communicate with other people or to learn something. But then there is the active presence. So different ways of expressing your agency and be able to explore or making choices and taking action. And so I tend to think of video games as the active presence bias towards you're essentially in a world, and you have all these different game mechanics, and you're making choices. But ultimately, it's to have you experience some sort of emotion. So there's always this going back to Robin Haneke's approach, where it goes back to some sort of emotional experience. And so I feel like that. filmmaking is very much centered in that emotional presence. And so using the consonants and dissonance cycles of narrative tension and music and visual storytelling in order to tell a story, but they really have control over the time and the release of the story of that time. And when you have that introduction of agency, then you have this inherent tension between the narrative tension of a story versus the agency of the individual. And finding that balance seems to be the existential tension of all interactive narrative. But I feel like the new thing with virtual and augmented reality and immersive theater is that now you're allowing yourself to put your body into the experience and to have a spatial experience of you moving your body through space or to have all of your sensory experiences be hijacked to be able to have this sense of actually being there and have this sense of environmental presence. So I feel like that there's the mental and social presence, active presence, emotional presence, and embodied presence, and that every experience is kind of trying to figure out some flavor of all these things combined together.

[00:15:22.623] Brenda Laurel: I totally agree. You've done a great job of defining some genres or suggesting them. I think that's right. And I'm not disrespecting the storytelling flavor or the 360 cinema flavor. I'm personally more interested in this domain of personal agency, what you're talking about. I mean, the trick is, and this is what my first book was about, the trick is... to design the environment and what happens in it in a way that predisposes people to make interesting choices. When they could do anything, you know, lead them in indirect ways so that the choices they make when they reflect on the experience come out to be a good story. But it's a story that they were a time-displaced collaborator in with the designer, you know.

[00:16:18.479] Kent Bye: Yeah. And another big hot topic in the realm of both spatial computing, XR, VR, and AR is ethics and looking at these ethical frameworks to be able to navigate these moral dilemmas. And so you're going to be on a panel here at Augmented World Expo. And I'm just curious what your moral dilemmas that you're looking at or some of these different ethical frameworks or trade-offs that you're trying to navigate with this kind of blurring of context and having a

[00:16:44.874] Brenda Laurel: New thresholds for where we draw the line in terms of what's okay, and what's not okay ethically Well, we're trying to look at some of the naughty problems like the question of trust and truthfulness so Because I think our current media environment has been corrupted in many ways And also because film and television have started representing digital media in ominous ways. So compare and contrast today's treatment of digital media and computation with Jurassic Park or some of the films that happened 10, 20 years ago that were much more positive. This predisposes users, interactors I should say, to a kind of level of distrust that has to be overcome. So that's one of the naughty ethical problems because on the one hand you're probably presenting a fiction to a certain extent. On the other hand you have to get people into a space where they're willing to do willing suspension of disbelief without feeling that they're in harm's way. So I think that's a big ethical issue that we need to work on. We are also looking, on the panel we're looking at intent of the designer in terms of emotional outcomes. So the joy of winning a battle or killing somebody is a kind of emotional outcome. Now my intent may be to sensitize people to the tragedy of war, That intent had better show up in the design. I feel like one of the ethical diseases of our time, and maybe of all time, or a lot of time, is this business of competition, of winning, of mastery, of success with a capital S. These are things that hurt us in many ways, that keep us from the kind of collaboration and cooperation we really need to call on right now as a species. So that speaks to the intent that a designer might have and the emotions that they might want someone to feel. We're responsible for that, designers. And I think it's really important. that we consistently touch base with our values as we move through the process of designing something, I guess, to make it truthful to yourself and your values. And then you've got to hope that the designers have good values, which is a whole other conversation. I was in the game industry too long.

[00:19:28.188] Kent Bye: Well, what that reminds me of is, in Chinese philosophy, the metaphor comparing the yang to the yin. So the yang is much more about that individuation process, the competitive aspect, and it's like a zero-sum game of, like, there's one winner. But the yin is much more of the ego disillusionment. So you see how you as an individual is connected to the larger whole. And I feel like that the hero's journey is very much more of the yang side Journey it's like you going out and going on this quest to be able to conquer the enemy and that it is a lot about that individuation process and I feel like that is very well suited to the frame a 2d frame and a screen where you have a certain amount of distance where You're watching other people do that. But when you are immersed in the experience it's almost like this turn towards the end, where it's much more about your own embodied sense of presence, your own sense of you being there. And it's about you being connected to a larger whole rather than you. I mean, you can go on that journey and that quest, but the affordances of VR make it a little bit harder for you to do a lot of locomotion. tend to be a little bit more focused on your sense of embodied presence. But I feel like there's a bit of, in the West, we have very much that bias towards that hero's journey and that Eastern cultures have the Monkey King or other films that are much more about this more Buddhist orientation of the ego disillusionment and to see how you as an individual are connected to a larger ecosystem. And I feel like there's something about the affordances of spatial computing and VR and AI that are introducing all these new elements of embodiment in the end.

[00:21:01.652] Brenda Laurel: I think you're exactly right. We've opened a capability space with spatial computing and these media types that we're talking about that's fundamentally different than the capabilities based in 2D game design for the reasons that you said. Embodiment itself is incredibly important in feeling more a part of the whole environment I'm really interested right now today and for the last couple of years in Gaian systems and in helping in designing things that naturally introduce the ideas of Gaian systems and sensory and concrete ways to people so that we start building environments that give us a better idea of how stuff is connected in an ecosystem, you know, in the whole Gaian system. So, for example, I've got a design for an AR plus VR plus simulation experience that is designed to help children raise a garden. And it comes from that guy in perspective. And I'm using avatars. All kind of near future, almost can do, but not quite stuff. That's an example of the kind of work I'd like to do. moving forward. I've become really involved with a group called Gaian Systems in San Francisco and their strategy is that maybe the way between fear and incremental adaptation in terms of climate change is simply to produce a new understanding in the public mind of how things work. So that can happen in a lot of different media types, but I'm especially interested in using AR in particular and VR to the extent that it does such great things with scale to help people come to that kind of understanding in a natural way without being preached to. So, for example, if you take the Meow Wolf model, where everything is concrete, reals, you could certainly do great stuff with a rhizome. You know, you could do amazing things if you just modeled a square yard of underground. So that's the kind of thing I'm interested in right now.

[00:23:23.166] Kent Bye: And talking to Sam Reynolds of Indiecade, he was talking about how games give you this ability to explore complex systems where you have these sets of rules, but you go down these different branches. And as you see the causal chain of making a choice and seeing how it changes the overall ecosystem, then you get much more of a complicated embodied metaphor of these complex systems. And I feel like that with just a 2D frame or just drawing out things statically, you have a very reductive, fixed ways of thinking about things. And that it's because we now have spatial computing that's very dynamic in moving things in 3D space, it's actually giving us spatial metaphors that we can start to understand much more complicated ideas of how these ecosystems actually work and kind of moving away from that reductive materialist perspective into... something much more like process philosophy from Alfred North Whitehead or Chinese philosophy to see how there are these things that are unfolding in these processes rather than these fixed static objects.

[00:24:18.769] Brenda Laurel: I think that's exactly right. It's really exciting, isn't it? I was talking with Donna Cox yesterday. I was interviewing her for a graduation talk I'm giving at University of Washington. She is head of the arts branch of the National Supercomputing Center in Champaign-Urbana. Are you familiar with her work? She has done, using a supercomputer, massive planetarium shows. The latest one is The Collision of Two Black Holes, and it's absolutely riveting. It's narrated, you know, by Benedict Cumberbatch, Oh, Be Still My Heart, but it's a different kind of specialization. A planetarium of immersion is also immersion, but there's a way in which you're not embodied. You're actually present out there in that galaxy that she's showing you. And I think that's a really interesting frontier, too.

[00:25:15.311] Kent Bye: Well, you had mentioned earlier about this gendered split of the kind of disembodied approach of the men that were looking at your experiences versus the women who...

[00:25:26.623] Brenda Laurel: 93, 93, 93 times have changed.

[00:25:29.106] Kent Bye: Well, I wanted to ask because I feel like there's a certain amount of, you know, philosophically, it feels like the feminist theorists and the philosophers have been talking about embodiment for a really, really long time. I mean, going back decades and decades and decades, the importance of the body. And so I'm just curious if that feminist philosophy and the talk of embodiment, if you're looking to anybody in particular that has been talking about that for many generations, and if that has given you any specific perspective since your early work was specifically focusing on embodiment.

[00:25:58.717] Brenda Laurel: Well, I think Char Davies is a real role model for me. the breathing UI that she invented. She did a piece called Osmos in 94, and she created a UI device that you strapped around your chest, and it was like diving. You'd inhale, you'd go up in the world. You'd exhale, you'd go down. Oh, if you exhaled a lot, you'd get into the code. It was just an amazing piece of inventiveness on her part. And she's now doing... different kinds of visualizations of natural systems. I think they're involving sound reflection and UV and other kinds of things that we can't see with our eyes to visualize environments and be present in them with these senses that we don't have particularly. That's cool. That's an extension of the body. So there's a way in which that's quote, feminist work, but it's also kind of cyberpunk, you know, to get out there and have that kind of experience. I think that's what I love about Donna Cox. Both of these women are making the invisible visible and palpable and creating the ability to be present within it. You know, I think it's fabulous work. I must say that in the early 90s, I would bet you that over half of the people who were doing VR were women and they were artists. They came from the art side. A lot of women had difficulty with it philosophically early on. There was a lot of resistance from women, too. It's like, why are you taking me into this fake world? I feel exposed. I feel vulnerable. This isn't right. This isn't natural. So I've been having sort of an ongoing discourse with certain quarters of feminism about the false dichotomy between technology and nature. And if technology is something that we extruded, it's part of us. For better or for worse, we're responsible for it. But it's not the other any more than nature is the other. These things are all part of our reality. And to the extent that we make technology, it's just, it's us. It's the extension of us. we still see resistance, not just from some feminists, but from other people. I'm sure you've experienced this, where people say, ah, it's bad, you know, it's fake news. So that's kind of an ongoing dialogue in feminism.

[00:28:34.618] Kent Bye: Yeah, when I talked to Jackie Mori back in 2014, and she made that same point, that there was a lot of women that were doing art within virtual reality, which was surprising to me, seeing what the gender ratio was at the very first Oculus Connect One, which was, you know, very much like maybe Two to five percent of the attendees there, but that was more of a maybe reflection of the tech industry and the gaming industry at large But maybe surprising for some people to hear that there is about half of the people that were involved in creating pieces What do you think it was at that time that was drawing these women to make these different pieces? I

[00:29:06.377] Brenda Laurel: I think it was art. If you look at the... I don't want to overgeneralize here, but, you know, you've got Peter Max, you've got Big Soup Can, why am I not thinking of his... Andy Warhol. Andy Warhol. You know, these guys are doing one kind of art, and it's not evoking the emotions that some of the art that women were doing in those times, like Georgia O'Keeffe, etc., although she's a little earlier... Women who were artists were really drawn to the medium because of embodiment, because it gave them a chance to extend their work out into an embodied space. And I think the kind of art that was popular in the male art scene, I'm really generalizing, didn't have that drive. It was going in a different direction. Now there may not be such a gender gap in terms of the kind of art people are making, I don't know. But I do think it was a natural extension, in a way, of the desires of a lot of women artists to get into an embodied world.

[00:30:16.113] Kent Bye: So for you, what are some of the either biggest open questions you're trying to answer or open problems you're trying to solve?

[00:30:24.055] Brenda Laurel: Oh, dear. Well, one that I'm really interested in is how do we create smooth transitions from AR to VR in a natural environment, in a field. I maybe can visualize with AR what kind of tree I'm looking at or what its leaves will look like when they come out. But I might want to stick my head in it and see how its vascular system works. I might want to get really small and go down and cruise around the routes. So that's a transition to model and simulation, a transition to VR. How do we make that smooth? I think that would be just a tremendous research problem to work on. I've pitched it to some people who don't have the money to support it, but that's my kind of nerdy, lavish dream. And I guess the other thing is that I want so badly for people to wake up to the kinds of intents we could have in making this work and the importance of enacting those intents for the good, capital G, because I think that's something we really need right now. And I don't think it's an accident that we've built ourselves a capability space in which we might actually do that effectively.

[00:31:49.534] Kent Bye: Great. And finally, what do you think the ultimate potential of virtual reality is and what it might be able to enable?

[00:32:01.040] Brenda Laurel: I don't think virtual reality is going to stay virtual reality. I think we will end up in this kind of blended space that I just tried to describe. strangely enough i think its greatest potential may be to help us connect ourselves with this world we're in with the natural world in a way my work has always been indexical to the natural world you know people say well why would you simulate an environment that's already here or why would you annotate it you know it's like it's saying look here notice this understand that feel this, you know? It's like a postcard from Paris. And then getting to go to Paris, you know? People will accuse you of making postcards when you do things that are indexical because they don't understand that they're indexical. they think you're trying to just substitute a virtual experience for a natural one and that's exactly not what i want to do i think we have the capability to become more connected with each other and with our earth and with gaia and the universe and everything with this medium and i think it will evolve in ways that we can't even imagine assuming we don't all die from climate change

[00:33:21.252] Kent Bye: I've definitely noticed that I've noticed light a lot more and pay attention to things differently because it's like you see the simulation and it trains you to see what the technology can do, but the fidelity of expression is so much more robust when you came out. So I do feel like, you know, Jaron Lanier, his thesis is that the human brain will always be able to tell the difference between the virtual and the real and that in some ways it's continuing to refine our Our sensory perception to be able to see more and more finer grain dimensions of the nature of reality itself.

[00:33:52.914] Brenda Laurel: Better attention paying is a skill that we develop. Also, I must say, just in an off-color kind of way. You know, after you have sex, the colors are brighter. You know, smoke a joint, the colors are brighter. In that way, things are going on in our brains as a response to certain kinds of peak experiences that train our senses up, I think.

[00:34:22.179] Kent Bye: Is there anything else that's left unsaid that you'd like to say to the immersive community?

[00:34:25.482] Brenda Laurel: I can't think of anything. You've grilled me. I'm exhausted. I need to go lie down.

[00:34:35.897] Kent Bye: awesome well thank you so much for joining me so thank you you're welcome it's been a pleasure thanks again for listening to this episode of the voices of your podcast and if you enjoy the podcast and please do spread the word tell your friends and consider becoming a member of the patreon this is a this is part of podcast and so i do rely upon donations from people like yourself in order to continue to bring this coverage so you can become a member and donate today at patreon.com voices of vr thanks for listening